A Movement in a Moment: The International Style

Discover how a 1932 MoMA exhibition helped introduce the entire world to the joys of modern architecture

During the summer of 1932 a new exhibition was touring the United States. Entitled Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, it was the Museum of Modern Art’s first architectural show, and had drawn around 33,000 visitors during its six-week run at MoMA in New York earlier that year – not bad for a display of largely foreign building models and plans.

Part of the exhibition’s allure lay in its promise to introduce Americans to a new and important style of architecture, which the show’s director, US architect Philip Johnson named the International Style.

“There exists in the important countries of the world today a new architecture,” wrote Johnson. “The reality of the International Style has not yet been brought home to the general public in America. This is due partly to its newness, but also because of its international character; few persons have had the opportunity of gaining a comprehensive view of the style in its entirety.”

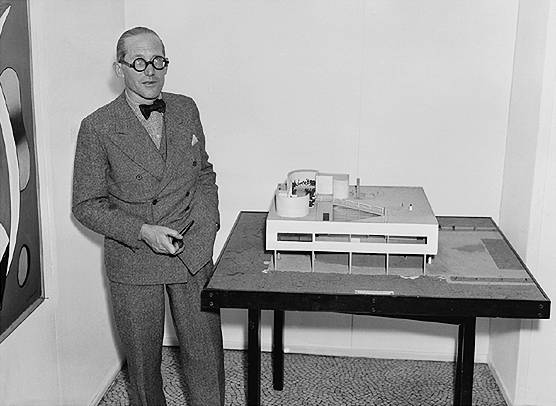

Johnson and his collaborators Henry-Russell Hitchcock had gained such a viewpoint, travelling extensively in preparation for the show. Their exhibition included US practitioners such as Richard Neutra and referenced the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, but also featured the creations of Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and other European talents.

Sixteen countries in total were represented in the show, with works dating as far back as 1922. Yet despite this diversity the show’s organisers believed the exhibition exemplified a single, unified movement.

"The International Style is probably the first fundamentally original and widely distributed style since the Gothic,” Johnson argued. “Today the style has passed beyond the experimental stage. In almost every civilized country in the world it is reaching its full stride.”

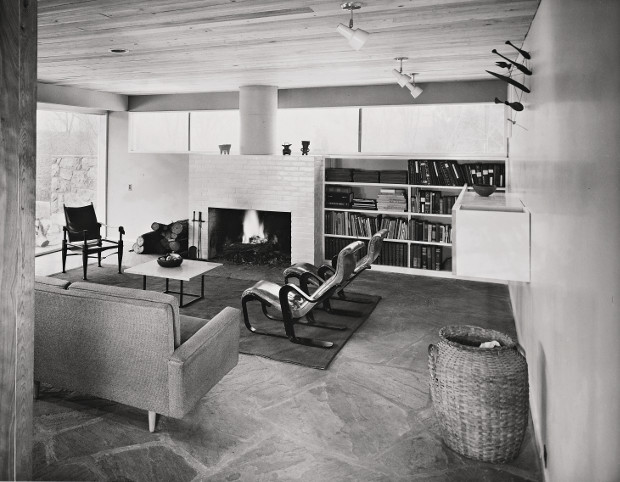

That style was essentially Modernist, with clean lines and almost no ornament, built from steel, concrete, glass and other industrial materials. Yet there was little of the high-minded European idealism of the Bauhaus in this exhibition. Gropius, Mies and fellow Modernist Marcel Breuer all fled Europe following the rise of the Third Reich.

However, this mismatch, far from stymying the International Style, may have actually aided it; without any clear ideological baggage, architects from Tel Aviv to Rotterdam, Brasilia to Caracas could draw from the movement, without fear of persecution.

More practically, the International Style did not suit one climate much better than another, and could be adapted to the frozen stretches of Finland as easily as the arid plains of Mexico or California.

European refugees, including Mies, Breuer and Gropius, all helped spread the style throughout the US, while other WWII emigrés carried out similar roles in Israel.

Not everyone in the world appreciated the International Style. EH Gombrich, in his all-encompassing book, The Story of Art, praised such 20th century building design for helping “us get rid of much unnecessary and tasteless knick-knackery,” while also outlining the shortcomings of designs where form mindlessly follows function.

“Surely there are things which are functionally correct and yet rather ugly, or at least indifferent,” he argued. “The best works of this style are beautiful not only because they happen to fit the function for which they are built, but because they are designed by men of tact and taste who knew how to make a building fit for its purpose and yet ‘right’ for the eye.”

It is also worth noting that Johnson is today best remembered for his contribution to postmodern architecture, a later 20th century movement that revived some of the ornamentation earlier architects sought to erase from the built landscape.

Nevertheless, the International Style helped architecture look both foward, and around, across the world, to formulate a manner of building fit for the globe. For greater insight into the work of Mies Van Der Rohe get this book; for more on Marcel Breuer get this one; and for greater insight on Le Corbusier buy this title.