David Byrne’s Dingbats and the art of living freely

The singer, songwriter and fine artist has something to say about the cities we build in our heads

Would you know a dingbat when you saw one? Not a dingbat, as in a stupid person, though, as David Byrne admits in the introduction to his new book, A History of the World (in Dingbats), “that’s the common usage.”

In the singer, songwriter and fine artist’s new book, Byrne uses the term in a different sense. Here, ‘dingbat’ refers to the incidental, typographical element, nonsensical to the readers, but legible to the professionals who once oversaw the production of books and periodicals; dingbats were used by typesetters to both give layout instructions to a printer (who, as Byrne points out, was “a person, not a machine”) and to create visual breathing space.

Technical developments mean texts no longer require these interjections, yet plenty of publications, including The New Yorker, retain these little space-giving glyphs, which over the years morphed into drawings or cartoons – engaging pictures unrelated to the writing they accompany.

During the early days of the Covid pandemic, Byrne began to produce a few hand-drawn dingbats of his own, initially to accompany an online publication he was launching. However, as the drawings began to take on a life of their own; he exhibited them at Pace in New York and has now drawn them together in this new book, for which he has also written some accompanying texts.

Can we, the reader, interpret Byrne’s dingbats as signs or directions, as printers once did, in times of old? Perhaps. “The drawings are not a direct commentary on specific societal issues laid bare – but maybe they begin to articulate how we feel,” he writes in his new book. “Joyous yet also frozen. Fragmented yet unified.”

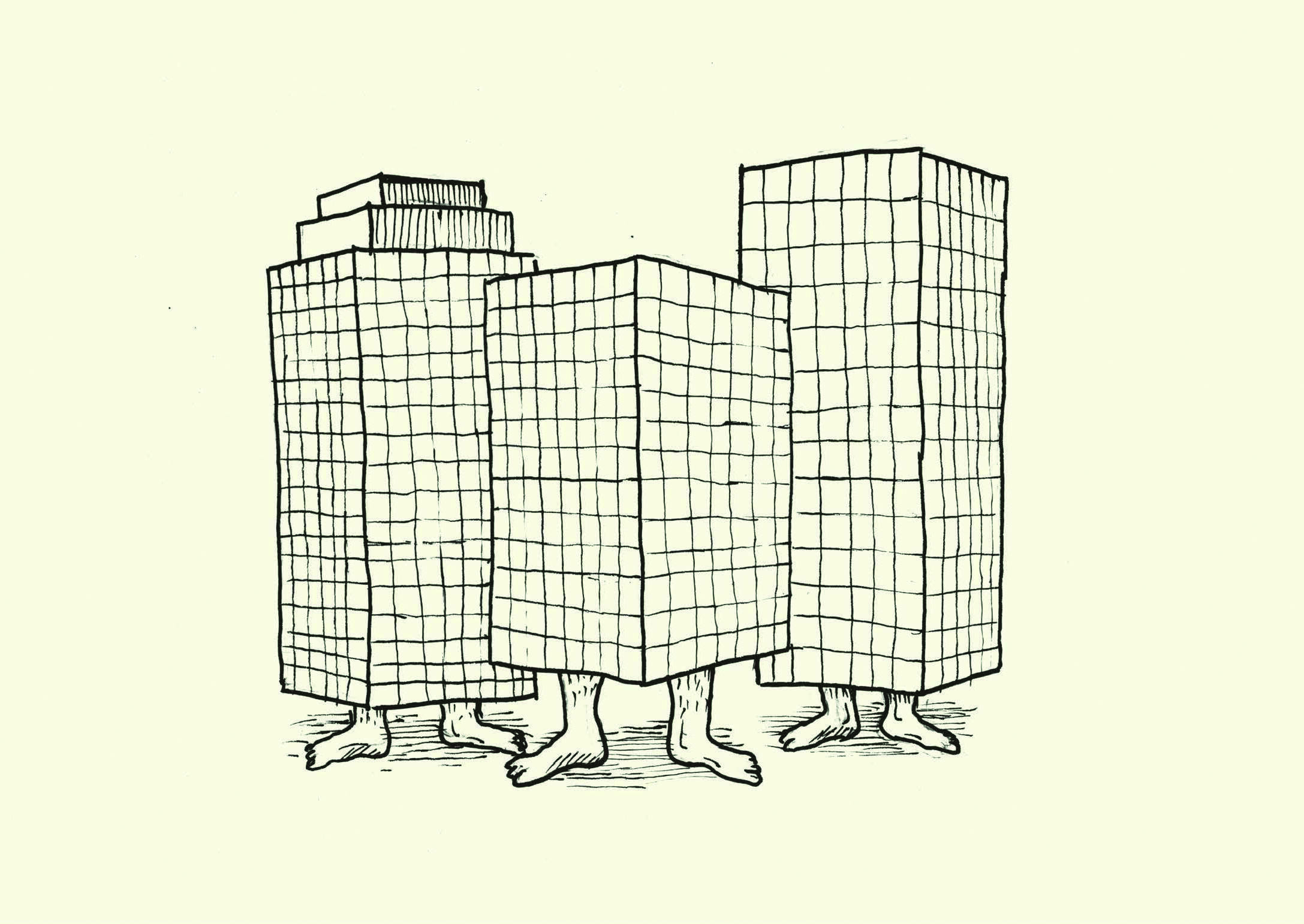

Life is Good. David Byrne / © 2022 Todo Mundo Ltd. from Part Five: Cityhead

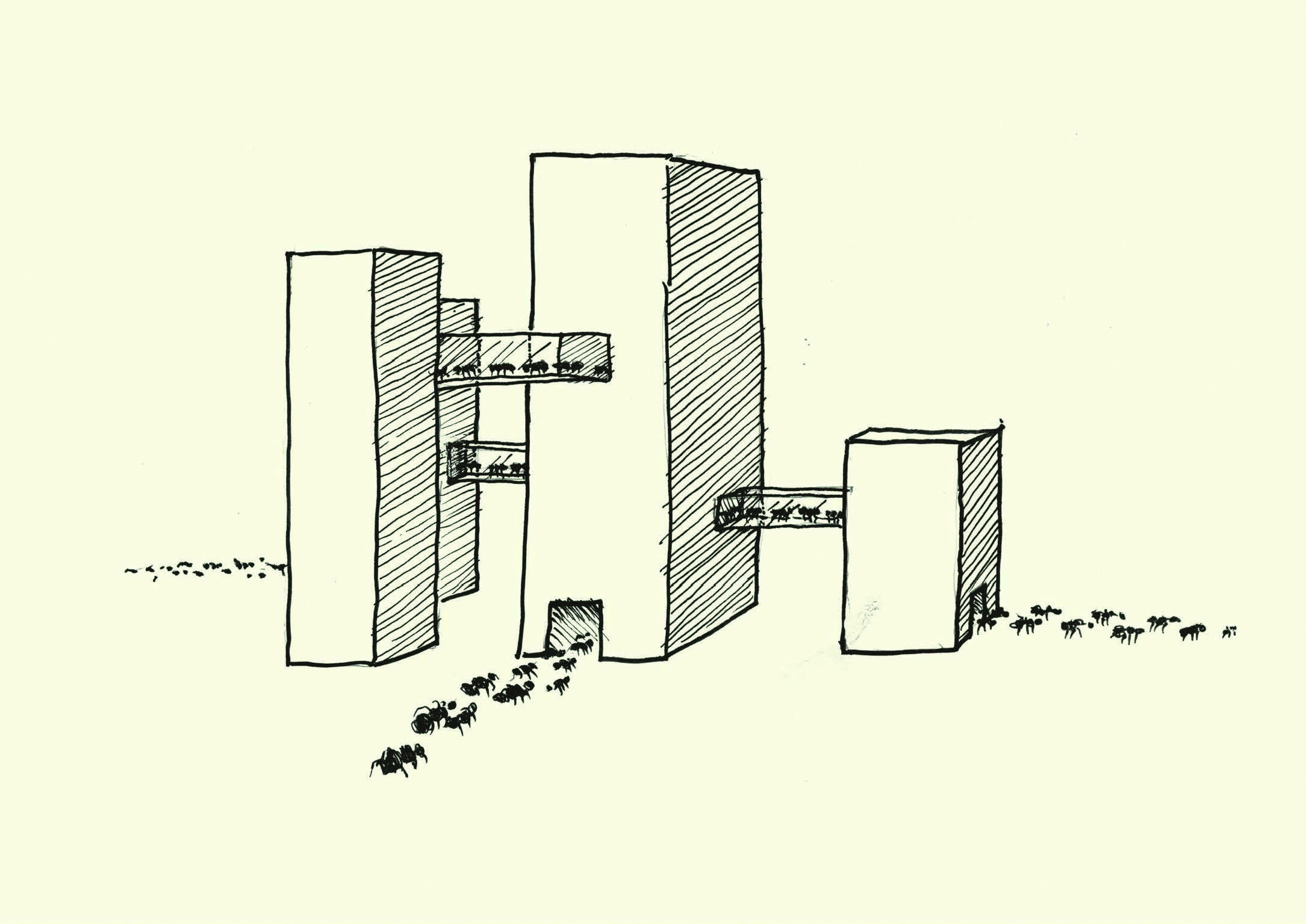

Consider this chapter introduction, entitled Cityhead, which runs just before a series of urban-themed dingbats. In a way it addresses our interior spaces, but in another sense, it says something about the city experience, or at least the city experience as viewed from within.

“We live in a city in our heads,” writes Byrne. “The buildings that surround us, along with our clothes and our hairstyles, we invented these things.

“Like termite mounds, they mirror, reflect, and amplify our assumptions and thoughts and our unacknowledged social structures.

“As inside, so outside. The cities are fantastical and beautiful. A world of places, people, and things, moments real and imagined, all jostle for space in there. People with prodigious memories decorate memory palaces and file their moments along streets and boulevards. These markers are invisible to others, but real as anything else to the inhabitants. A literal stroll down memory lane.

“Everything in its right place, labeled and grouped according to elaborate and ever-changing criteria. Only you can find the way – in the city in your head. We replicate and impose these ways of categorizing and naming things on the outside world. Our template is guard against chaos and an ever-changing filter.

“The categories offer us both liberation and confinement. Geometries of freedom and hierarchies of restriction.

A History of the World (in Dingbats)

“Chaotic and organized,” he concludes, “passionate and dissolute.” Have you experienced this urban environment? Then perhaps you’d like a little more guidance courtesy of Bryne’s words and pictures, and see more of his dingbats. You can order the new book here.