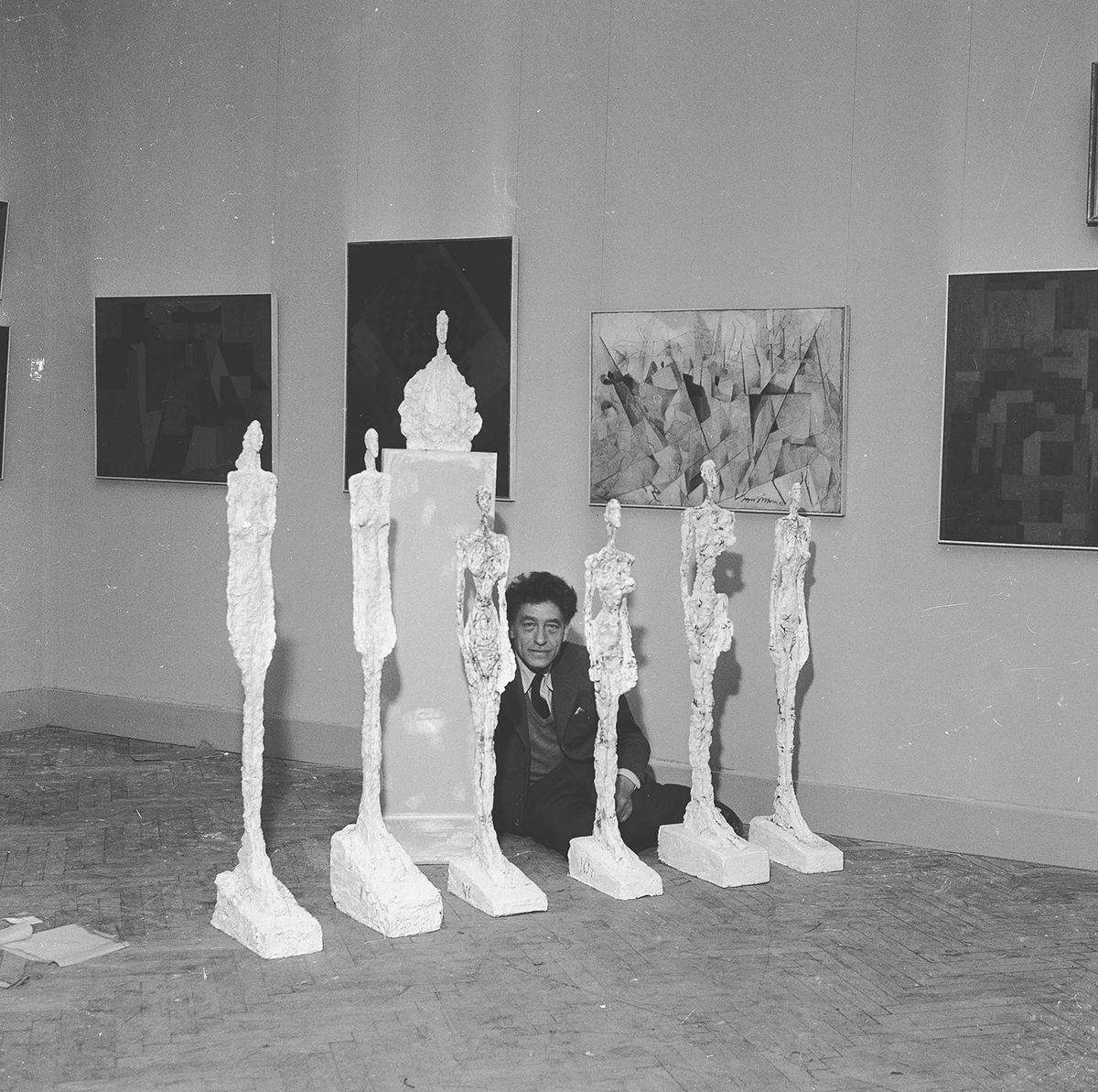

Four ways of looking at Giacometti

Heading to the Tate show? Then here are a few tips for getting the most out of the great man’s art

The Tate Modern’s blockbuster Giacometti retrospective – the first major show in the UK for 20 years – opens in London today. Planning to visit? Then you might benefit from a little bit of light reading, courtesy of our art books. Here’s four things to look out for in the show.

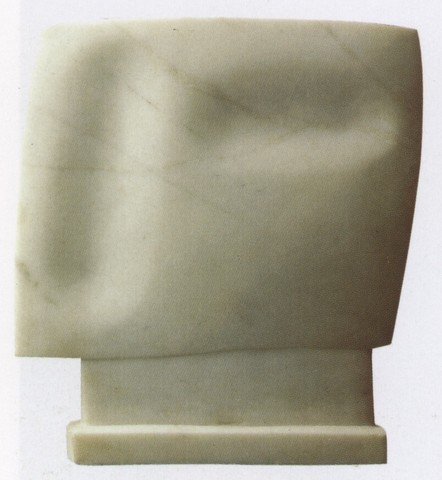

Simplicity EH Gombrich examines an early Giacometti sculpture, Head (1927) in The Story of Art. The great art historian acknowledges that it “may remind us of the work of Brancusi, though what he was after was not so much simplification as the achievement of expression by minimal means. Though all that is visible on the slab are two dells, one vertical, one horizontal, it still gazes at us.”

Space In our sculptural survey The Elements of Sculpture, Giacometti’s 1948 sculpture Standing Woman is examined in spatial terms. “In Standing Woman, the normally passive space surrounding all objects in our world has violently torn away the surface of the figure, exposing its linear core,” writes Herbert George. “And the emaciated sculpture is consumed by the same space we had assumed to be passive. The space that surrounds and supports Standing Woman has become a present force more real than the materiality of the figure.”

Scale Elements of Sculpture also draws on Giacometti’s 1950 work The Forest (Composition with Seven Figures and a Head) when describing the uses of scale in sculpture. “On first view, the impossibly long thin proportions of the seven figures are one of the most striking aspects of the work; their heads are too small in proportion to their elongated bodies while their feet are too large,” writes George.

“The tallest figure is 23 inches high and they are all female. The two figures at the back are much smaller than the five at the front, creating a false perspective that visually pushes the taller five forwards. But when we consider Scale, it is the portrait head at the rear that becomes the most interesting. The figures outnumber the head and they are the ‘forest’ that defines half of the work’s narrative. The other half, the head, interrupts their closed conversation. And it does so because of its scale. With its long neck and broad shoulders, it is proportionally much larger than the figures and, even though it is shorter, it has a more life-like presence than the figures. This discontinuity in scale, proportion and real size challenges the viewer with a seemingly impossible paradox. Both the figures and the head share the same ground plane and space, so if we accept the scale and proportions of the figures, how can we accept the presence of the bust in the same composition? Giacometti utilizes Scale here to construct a disturbing but carefully considered improbability that challenges not only our imagination but also our innate sense of the probable.”

![Head of Woman [Flora Mayo] (1926) by Alberto Giacometti. Image courtesy](/resource/004.jpg)

Sympathy Giacometti prized life over art. “In a burning building,” he is quoted as saying in our book Art Is the Highest Form of Hope & Other Quotes by Artists, “I would save a cat before a Rembrandt.” Some read this as evidence of some animal-rights agenda, yet it’s probably wiser to see the remark’s emphasis on life and the lived experience, in a world filled with abstraction, industrialisation and loneliness. As Morgan Falconer puts it in his post-war painting survey, Painting Beyond Pollock, “Europeans like Bacon and Giacometti would isolate the human figure in order to suggest its lonely confrontation with metaphysical questions.”

Find out more about the Tate's show here. Buy a copy of Elements of Sculpture here; buy a copy of The Story of Art here; get Painting Beyond Pollock here; and get Art Is the Highest Form of Hope here.