How Emory Douglas branded the Black Panthers

Douglas's engaging designs have earned a place at Tate Modern and the Design Museum this summer

Like the iPhone, Facebook's ‘like’ emoji and Burning Man, the Black Panther Party is another world-famous creation designed in California. Yet, unlike those later conceptions, the Panthers struggled against social injustice and government suppression in order to spread their message beyond their base in Oakland and out to the wider world. Emory Douglas, the US artist and erstwhile Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, played a key role in this struggle.

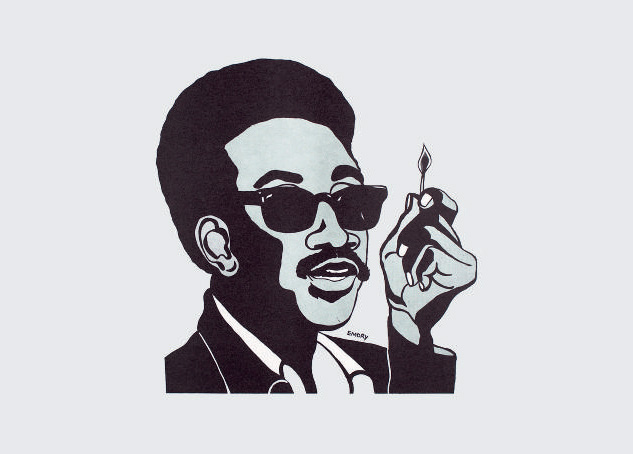

“Emory Douglas was a graphic designer who had first encountered the practice during a stint at a juvenile facility, then studied commercial art at the City College of San Francisco,” explains professor Louise Sandhaus in our book, California: Designing Freedom. “Inspired by Malcolm X’s edict of ‘self-respect, self-defence, self-determination’, Douglas made social justice his cause, joining the Black Panthers as its Revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture.”

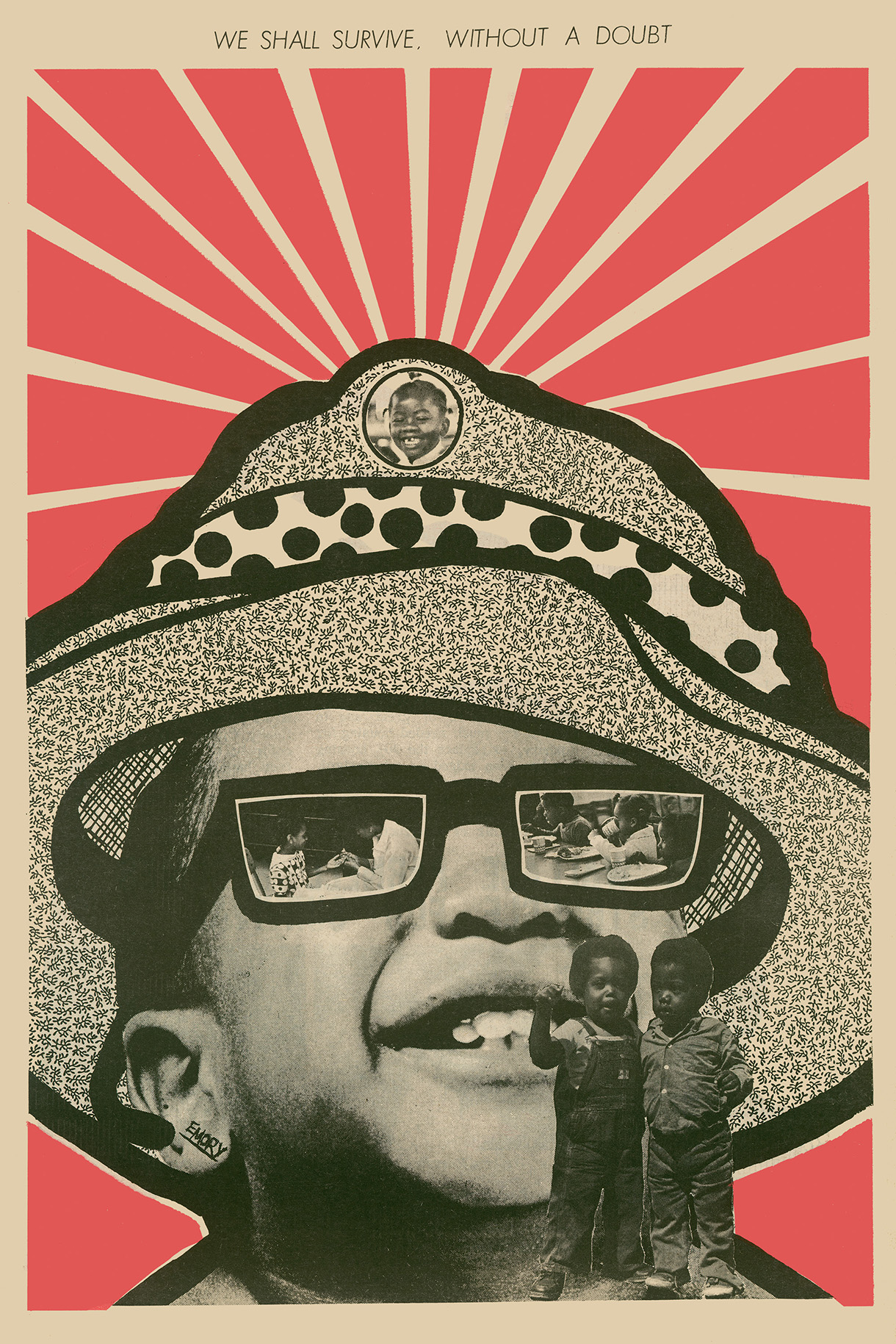

From 1967 until the end of the 1970s, Douglas created posters, leaflets and a weekly newspaper for the Black Panther Party. Today, many of his works look fairly inflammatory; yet other pieces, promoting, for example, the Panthers’ free breakfast programme for children, demonstrate how the party reached beyond armed resistance.

“While the mainstream press depicted the organization as violent and militant, in the compassionate hands of Douglas the Panthers attained a more nuanced and three-dimensional public image, powerfully communicating sorrow as well as outrage,” Sandhaus writes. “His designs forged a sense of community and a coherent political voice, spread awareness of government activities and rallied dissent over the lack of healthcare, education and food programmes.”

This summer, both the Tate Modern and the Design Museum in London are showing Douglas’s work; the Tate has included him in its exhibition Soul Of A Nation: Art In The Age Of Black Power, and the Design Museum features Douglas in California: Designing Freedom.

For those unfamiliar with the Panthers’ history, it is perhaps surprising to learn the organisation had a Minister of Culture. Yet on closer examination, the remarkable thing about Douglas is not his official appointment, but just how good a fit he was for the party. The artist’s immediate, uninhibited visual style expressed some of communitarian sense, softening the Panthers’ politics, even when he Douglas depicted a policeman as a pig, facing gun barrel.

“In his wisdom, out of habit or the convenience of the means at hand, Douglas deployed a visual vocabulary that resonated with the people, his people, because it was familiar,” says Sandhaus. “His designs spoke in the vernacular of a community.”

Douglas’s relationship with the Panthers ended when the party disbanded in the early 1980s, yet he continues to work, creating the same campaigning imagery that speaks to both one particular community, and the wider world, including – at least for this summer – London’s gallery goers.

For more on Emory’s place within West Coast creatives order a copy of California: Designing Freedom here; for more on contemporary artistic resistance, get Visual Impact.