Latino artists face down Modernism

The effect of Modernism on Latin America is charted at New York’s Bronx Museum of the Arts

Do you know where the Brazilian flag’s text ‘Ordem e Progresso’ comes from? It’s an adaptation of the French philosopher and founder of Positivism, Auguste Comte’s motto, “Love as a principle and order as the basis; progress as the goal." Such high-minded, European ideals were common across a lot of Latin America a century ago, and often found their expression in these country’s buildings. A current exhibition at the Bronx Museum of Arts, Beyond the Supersquare, examines “the complicated legacies of modernist architecture in Latin America and the Caribbean through the perspectives of 30 contemporary artists.”

More than 60 exhibits are on display, ranging from photography, video, sculpture, installation, and drawing, many calling all this supposed order and progress into question. Today, we might look back on Le Corbusier and co.’s architectural legacy with nothing but nostalgia and admiration, yet, as the show makes clear, in Central and South America, the effects were more nuanced.

There, the history of Modernism can be divided into a hopeful, utopian, left-leaning period in the early to mid century, followed by – as the New York Times’ review of this show puts it – “a rash of right-wing military coups” that swept across the continent in the 1960s and 70s.

Works from the earlier years were abandoned, or repurposed for less-benign ends, and even the more forward thinking architects found that their buildings weren’t always wholly fit for purpose. The show’s title takes its name from Oscar Niemeyer’s superquadras, or all-encompassing ‘supersquare’ housing blocks, replete with churches, theatres and schools. Residents had no need to leave home and, perhaps the architect imagined, no desire to.

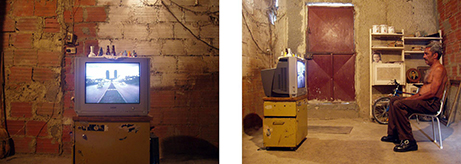

In response to this legacy, the Brazilian artist Andre Komatsu has created, Base Hieráquica, (Hierarchical Basis), a simple readymade, wherein popular water glasses withstand the weight of modern bricks and breezeblocks, while a more bourgeois, stemmed wine glass appears to have smashed; Venezuela’s Alexander Apóstol’s video, Documental, shows his country’s labourers watching a film about Venezuela’s wonderful post-war boom, while sitting in the jerry-built housing which were supposed to house them temporarily, until new, highly modern blocks were erected, but, alas, still stands.

Meanwhile, the Canadian-born, NYC-based visual artist Terence Gower has created a temporary pavilion. Called SuperPuesto or PostSuper, it has perforated wooden red, blue and yellow walls, a ‘butterfly’ roof, and is a, more or less, tropical take on Marcel Breuer’s 1949 House in the Museum Garden in MOMA’s sculpture garden. It’s a beautiful creation, but you have to wonder about its practicality. What better way to illustrate the pitfalls of planned order and progress, beyond the order confines of the Villa Savoye?

For more on this exhibition, which runs until 11 January, go here. For greater insight into Latin America’s greatest 20th Century artist consider The Curves of Time, the memoirs of Oscar Niemeyer; for a good grounding in the period, try Modern Architecture Since 1900, a penetrating analysis of the modern architectural tradition and its origins by William J R Curtis; and for an all-encompassing portrait of Brazil today, architecture and all, pre-order our forthcoming book.