How Toulouse-Lautrec mixed high art and low life

On the painter's birthday, learn how he made cabaret girls and prostitutes a worthy subject for fine art

We might think of Warhol’s Factory, with its addicts and rent boys and transvestites, as the place where urban lowlife first met fine art. Yet, as any decent scholar will tell you, Paris was the nineteenth-century capital of the art world, and in that city’s nascent cabarets and brothels, the artist Toulouse-Lautrec first caught the seamy side of industrialised, urban life, and transferred it to the mass medium of print.

The artist was born on this day, 24 November, in 1864, to an aristocratic family in southern France, descended from the medieval counts of Toulouse. Although his parents were cousins, the artist’s physical deformities, in particularly his abnormally short legs, were not attributed to genetic defects, but rather to childhood accidents in which he suffered leg fractures.

Displaying an early aptitude for art, Lautrec entered the Parisian studio of academic portraitist Léon Bonnat in 1882, at a point when the city’s licentious reputation was hardening.

“Montmartre in the 1880s, was just beginning to enter its period of greatest glory,” writes the British critic Edward Lucie-Smith in the introduction to our monograph, and Lautrec delighted in the pleasures afforded by this seamy district of the capital.

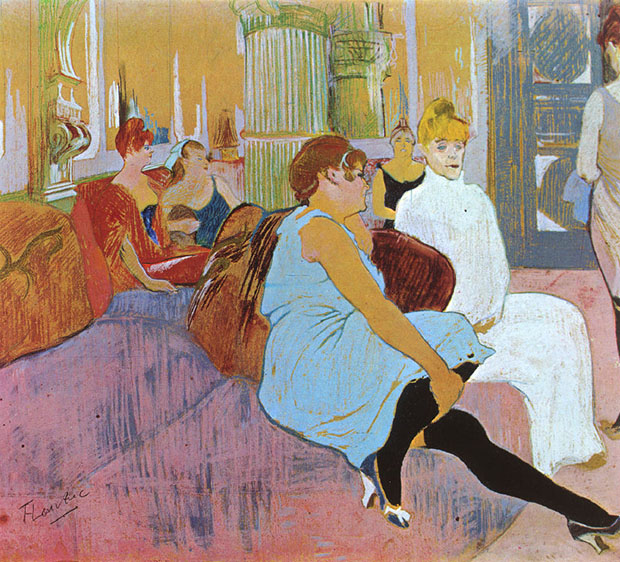

As a deformed nobleman with a significant sexual appetite and a taste for alcohol, the lure of vice isn’t an especially remarkable aspect of Lautrec’s life. However, his fascination with the Parisian demi-monde extended beyond base gratification. The artist took to depicting dancers and prostitutes as his contempoaries had captured ballerinas and card players.

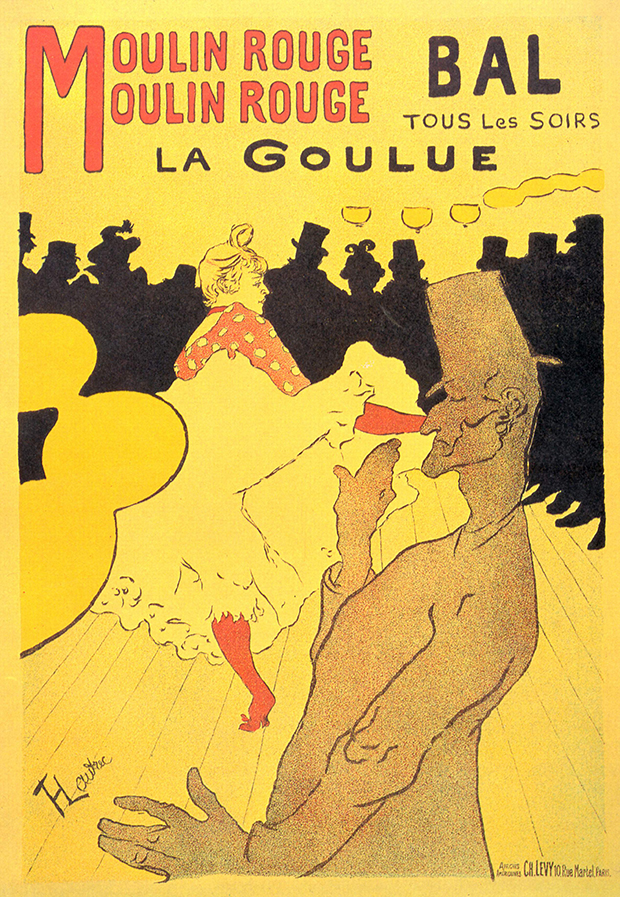

Scenes from everyday life had been a popular subject at the time, but Lautrec’s “typical subject matter was not the working class as such, but those who lived on the margin of society.” writes Lucie-Smith. “Lautrec began as a painter of dance-halls and cabarets; a poster done for the Moulin Rouge in 1891 marked the beginning of his reputation with his contemporaries.”

Indeed, to this novel subject matter, Lautrec applied equally innovative techniques. Although such friends and contemporaries such as Van Gogh and Degas influenced him, the artist also drew from diverse sources.

“He was, in particular, influenced by Japanese prints, which were then becoming fashionable in Europe,” writes Lucie-Smith. “From the [Japanese] printmakers he learned not only how to use flat colour areas, bounded by a definite outline, but how to choose a point of view that enabled him to express a personal vision of the subject.”

These bold, bright, democratic works were often created for posters, which were pasted up on the streets of Paris, showing the city’s nightlife with a peculiarly aristocratic disregard for polite opinion. Despite producing many more canvasses, these modern, ribald public works were, ultimately, his greatest bequest to artistic tradition.

As Lucie-Smith points out, Lautrec’s posters were on the city’s streets when Edvard Munch first visited in the early 1890s, and “when one looks at Munch’s paintings one often seems to see Lautrec’s techniques taken a step further.”

Perhaps more importantly, Pablo Picasso would have also seen Lautrec’s posters when he first came to the city, in 1900, a year before Lautrec’s death, and produced a trove of Lautrec-like imitations during those early days in the city.

Although Lautrec passed away at the relatively youthful age of 36, his work still resonates; his subjects and techniques began the assault on the divisions between high and low art – a battle the Warhol and co would finally win, in a different city, a few decades later.

For greater insight into this important artist, buy our monograph, here; for more on this period and others, buy a copy of EH Gombrich’s The Story of Art.