Zach Harris - Why I Paint

Exploring the creative processes of tomorrow's artists today - as featured in Vitamin P3

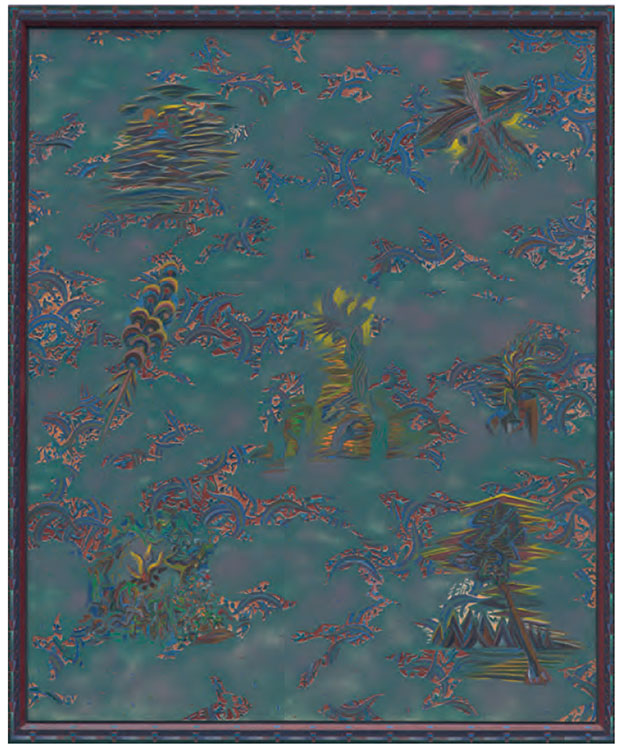

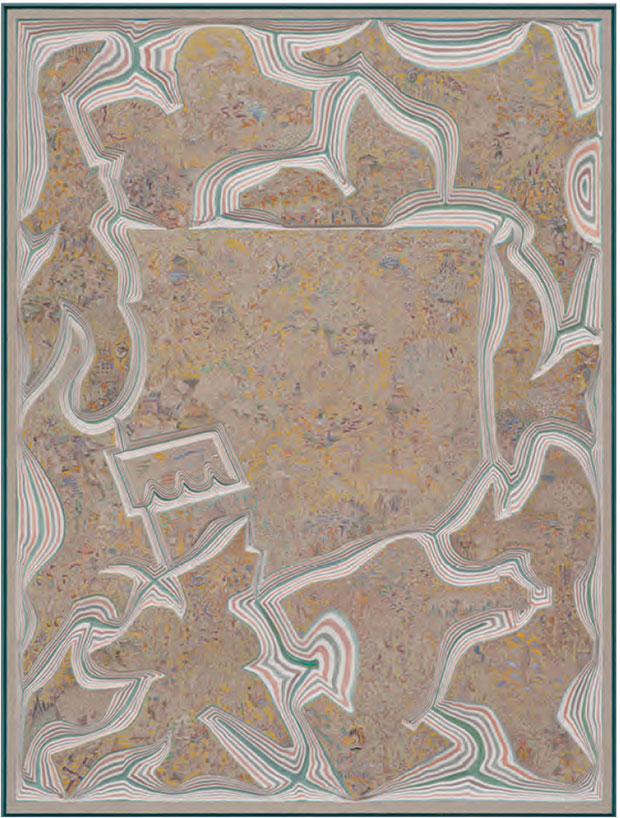

Though modestly sized, Los Angeles-based painter Zach Harris’s works allude to an endless geography – both psychic and physical – that remains beyond our reach. Harris brings an unexpected drama to his abstract works. There are endless worlds to see in his obsessively detailed paintings. Deeply influenced by elaborate settings and details in Renaissance-era paintings, Harris sets his works within ornate frames which, like the paintings themselves, often rely on a subdued colour palette: earthy tones and neutrals, shocked through from time to time with a psychedelic blue. The Byzantine patterns created through layers of paint and carved grooves in the wood of the frame mirror and expand the micro-worlds created at the centre of the image. Here, the Vitamin P3-featured painter tells us what interests, inspires and spurs him on.

Who are you? Zach Harris. Also Mipham Lhaga (“Infinite Joy”). I was born in Santa Rosa, CA, but grew up from an early age in Los Angeles, where I have family going back four generations. My mother is a US History teacher and my father is a musician. I went to UC Santa Cruz for a year, then moved to New York City, at 19, to attend the New York Studio School, also for a year, then received my BA from Bard College and MFA from Hunter College. Each school had its paradigm and thought it was the best. I lived in NYC for 13 years then moved back to LA seven years ago, where I happily live with my partner Kate Wolf and our Chihuahua Eddie Roberto.

What's on your mind right now? So much! I have about 20 different pieces going in my studio, all at various stages of development, all having their own concept, narrative, surface, and visual language. It’s overwhelming and exciting, but there are themes and practices they share. I’ve been working on a series of large functional calendar paintings of the year 2020 (or 20/20), where I play with the structure of days and months to create algorithms of colour and form. The paintings also have representational and symbolic elements mixed in. They are pretty crazy. I’m also doing, mostly in the morning, very detailed Bosch-like regressive drawing of teeming, surreal figures and scenes, done in ink on raw linen, which then gets painted on and integrated into carved wood panels, making a sort of tapestry/painting/object thing, also large. I seem to gravitate towards making complex, time intensive, durational painting objects. Not 2-D, not 3-D, more in the 2.25 D range. It's very 4-D though. You have to spend time with them at their actual scale and with the full compliment of peripheral vision and framing to notice the modulations in depth, real and illusory, and the way the picture’s shapes and marks resolve into vibration. Monocular camera vision and scaled down reproduction never captures this. Nothing is flat with two eyes.

How does it fit together? It's not a concern. It’s not for me to decide or consciously know. Should an artist conceive of their retrospective when they aren’t yet 40? I don’t think it should “fit”. We aren’t talking about carpentry, where things “fit” or don’t. It’s painting, which exists as a flashing image on an imaginary, metaphysical plane. It’s there and not there. The art form is based on an immeasurable degree of illusionism and psycho-visual projection, which tends to complicate most concepts, even that of “Painting.” But the making of a painting has its own kind of accuracy and rightness which is even more demanding in the sense that not only is nothing black/white or fitting/not-fitting, but there is such a ton of gestalt! It’s Kant’s idea of the “mathematical sublime” and “infinite sublime” of overwhelming but conceivable (“mathematical”) or inconceivable (“infinite”) parts to the whole, which drives aesthetics and creates the sublime experience. (“Beauty” is an entirely different problem, equally complex.)

I think many painters including myself, especially in these MFA days when everyone has to teach themselves to paint, are often just feeling their feelings and dealing with hunches, or worse they think they might have it figured out. When looking at a painting in person, there are so many high frequencies all inter-relating in a cosmic steam that a painting can basically resolve itself into infinity. Within a single small shape one can detect worlds within worlds where logic fields resolve and contrast endlessly with one another. A picture’s apparent light can melt shapes into each other. Plus there is an overall inert, pathetic quality to a painting that has to be accentuated and transcended. A good painting will feel right from one to 100 feet away, and every distance in between has its particular feel and resolution. A “painting” is not really a single object or a fixed image; it’s everything in between, and that’s why it never stops being interesting and it doesn’t need to “fit.”

What brought you to this point? I grew up drawing, and have never stopped. I drew my way through the sludge of school, and I’ve been tunnel-vision obsessed with painting and visual art since I was about 17. I spent countless days wandering around museums, sitting in churches and temples, traveling to see some distant masterpiece, basically analysing all types of painting and whatever caught my interest, such as architecture or furniture. Nothing satisfied me more than to stare at a painting for as long as I could, watching as it imploded and revealed itself. I would immerse myself into the trance of the painter’s vision until it was like my own. It’s the best way to understand a painting, besides actually drawing or copying it, which I also did. This immersive staring went hand in hand with my meditation practice, which I was probably overly serious about at the time. Meditation, trance, and durational looking were a major influence on my studio practice and are still an inspiration for my work.

Can you control it? Tricky double-edged question. The only thing you can “control” is the vehicle; the inherent properties that are always present in an artwork. The more sensitive you are to the relations of these forces, the more control you can have, and the further and crazier you can drive your vehicle. But it can’t just be a decorative bourgeois joy ride, where you’re moving yellow over here and red over there until it looks nice, or making some simple “flat” shapes that never transcend themselves to become a controlled, composed illusionistic space or form. And if you keep driving on the same track, popping the same wheelies in the same spots, the nervous system immediately knows it and your work loses meaning and vitality.

As artists and viewers, we want to drive where we’ve never been, where things like formula and finish and Art are not relevant. The best paintings are puzzling and uncanny; perfectly controlled/uncontrolled in the most surprisingly right ways. A painting should make for a memorable, thrilling experience that we can never quite figure out. Then it becomes magic, or human will controlling Nature, the vehicle. This is the double-edge sword play that can’t be faked or digitized or assistant-ized.

“Great” paintings prove that a “great” amount and variety of control are possible. But if something is overly controlled its a problem. The control question becomes like the Chicken or Egg question. There is no conceptual answer but there is a purpose to the question: to feel the vast space that opens up in the mind as we puzzle and wonder about the relationship. This “frame of mind” is especially needed for a painter.

Have you ever destroyed one of your paintings? I guess the quickest way to finish a painting is to destroy it! The quickest way to ruin a painting is to “finish” it, as Delacroix said. You can’t destroy the initial thought seed impulse of inspiration though, which is the real content and message. For me, the possibility always exists that some brilliant outlandish move will solve the mystery riddle that I’m stuck on.

I am somewhat sympathetic to the current trend for making quick, thin paintings that jump off the wall, but what I value far more is the process of layering a painting and developing an image over time, losing it and finding it until it finally becomes something you could never have imagined at the beginning, yet perhaps secretly always dreamed of.

If an artist is afraid to lose and/or find an image or a space, we sense his/her hesitation and lack of exploration. As viewers we are hardwired as hunters and gatherers. We smell fear, sniff out clues, and intuit immense amounts of psychological information. A painting is like the brain itself; there is so much there that is functioning but we don’t know how or why. It can be difficult to feel secure and take risks in the midst of all this, especially when you have a tight deadline, or if you’re concerned about the final product, or if the new work will “fit” with the older work, etc. All of these are common demands in our market system, but they are often met with sarcasm or nihilism, which saps the life force from the process and leads to derivative output. I think that’s usually why most gallery shows are underwhelming. It’s sort of sad, but I would be just as happy going to a thrift store to look at paintings as I would a gallery - plus you can actually afford to buy something! The MAN destroys painting.

What’s next for you, and what’s next for painting? If we don’t destroy ourselves we won’t destroy painting. Painting and visual art is an extension of an archaic need/impulse to make images, to see how something looks, and to simply get across information visually. There are painted images that are 35,000 years old, and they are sophisticated! There are fascinating images from every epoch, every culture. In essence, image making IS civilization. Both are expressions of our human mind ordering disparate parts into a cohesive whole. As far as a material vehicle, the coloured mud is too convenient not to be used, at least here on Earth. The tactility of our bodies responds to or “feels” the nutrient-rich tactility of paint. Even in a giant floating outer space city of the future, we would still probably enjoy, even crave, a little impasto.

Maybe that’s what’s next for painting: digital impasto. But painting doesn’t really progress, and obviously doesn’t improve or advance. There is always something new or singular to be done however. In that way we can contribute to the wisdom of painting. More important though is to use the painting process to become aware of ourselves and our surroundings, there by perceiving the cause and effect of our thoughts and actions, helping us ultimately to give back, via painting, to the culture that gave us the opportunity to paint in the first place.

Zach Harris shows at David Kordansky 2018.

Vitamin P3 New Perspectives In Painting is the third in an ongoing series that began with Vitamin P in 2002 and Vitamin P2 in 2011. For each book, distinguished critics, curators, museum directors and other contemporary art experts are invited to nominate artists who have made significant and innovative contributions to painting. The series in general, and Vitamin P3 in particular, is probably the best way to become an instant expert on tomorrrow's painting stars today.

Find out more about Vitamin P3 New Perspectives In Painting here. Check back for another Why I Paint interview with a Vitamin P3-featured artist tomorrow. And if you're quick, you can snap up works by many of the other painters featured in Vitamin P3 at Artspace - the best place to buy the world's best contemporary art. And be sure to check out more of Zach's work at David Kordansky Gallery.