INTERVIEW: Stephen Shore: 'I didn’t like getting criticism but it didn’t cause me to doubt what I was doing'

In part two of our American Surfaces interview Shore talks about Instagram culture, a trip to New Orleans with William Eggleston and what Nan Goldin told him

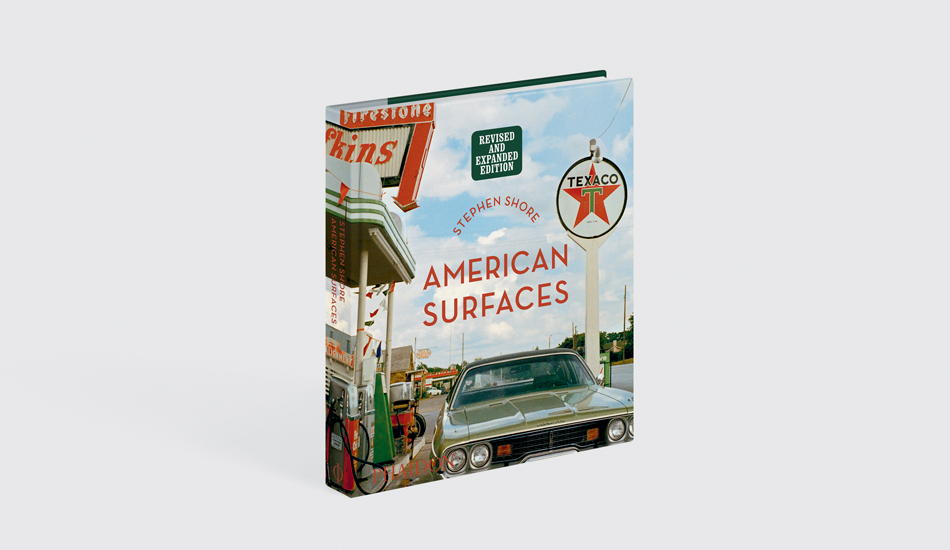

In his early 70s photo series, American Surfaces, Stephen Shore demonstrated both how colour photography – once largely the preserve of amateur photographers - could capture the natural beauty and the commercial pop of small town America.

Through his lens, he showed how a simple petrol station could stand alongside a Claude Lorrain painting. Since those early road trips, he’s applied a similar technique when photographing people and places in Italy, Israel and Ukraine among other places. However, this native New Yorker has never forgotten about small town America. The new version of his legendary book American Surfaces features 50 more photographs than the original did.

Shore saw himself as an explorer on the trips he made - even going so far as to visit a New York tailor and have a safari suit made.

What he brought back has come to define a form of American photography in the 20th and 21st centuries and finds a mirror in an Instagram age. In the first part of our interview, published earlier this week, Shore spoke about how he "was interested in making pictures that looked like the way I saw things, rather than making pictures that looked like photographs."

In part two of our interview he opens up on how this view finds a current home on Instagram and talks about his influences and those he influenced; and a memorable trip to New Orleans with William Eggleston...

Take us back to the first showing of American Surfaces at New York's Light Gallery in late summer 1972

It was really the best photography gallery in New York on upper Madison Avenue it was like an art gallery with white walls and good carpeting, they represented Paul Strand and Andre Kertesz, and Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander and all the work there was black and white. All of it was over matted and framed as you would present an old master print.

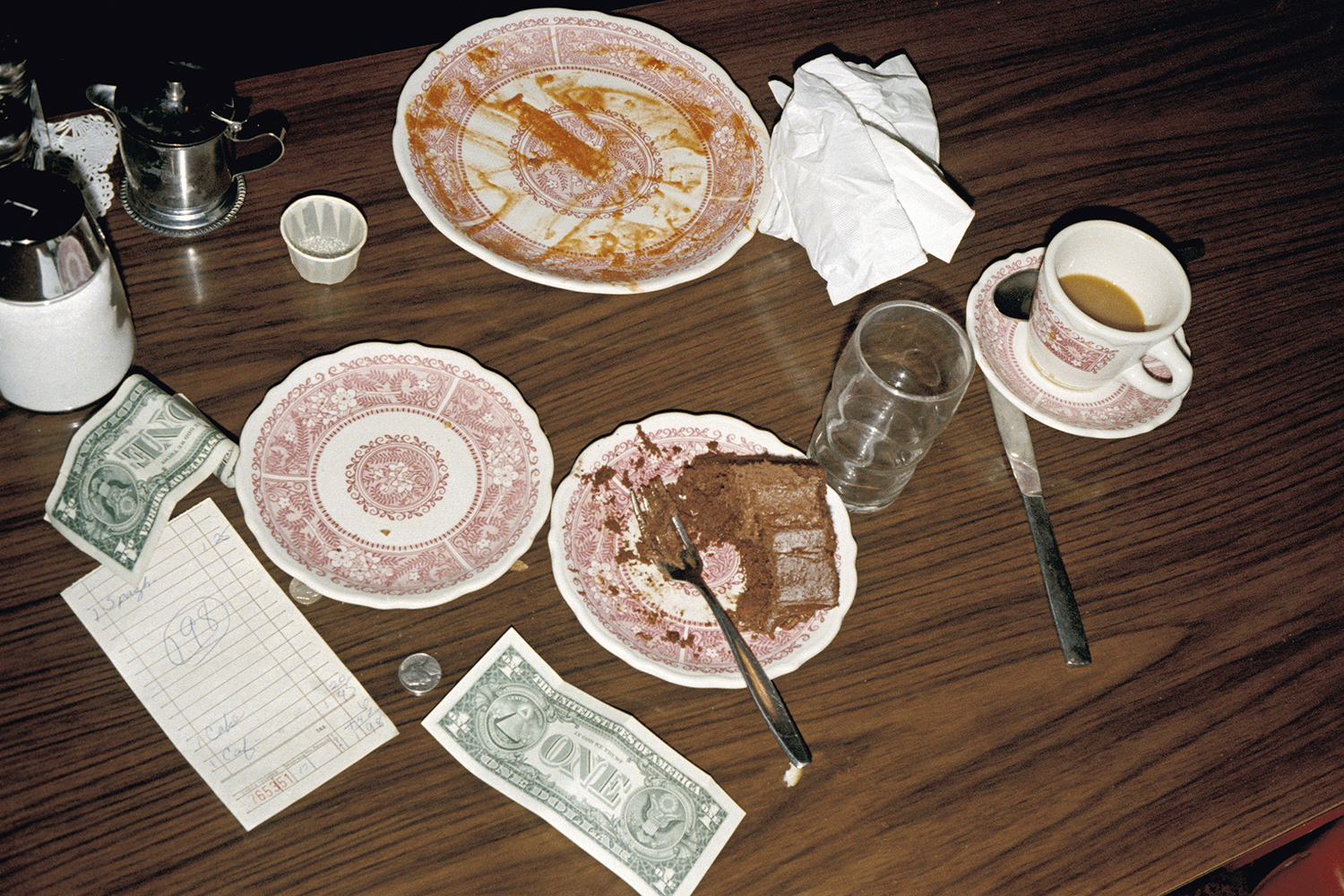

My prints were colour. They weren’t behind glass They weren’t framed or over matted. They were pasted on the wall. They were not printed by me.They were prints not even made by a professional lab!

Didn't Cartier Bresson make his own prints though?

Yes, but he had a good printer! These were made by Kodak! You know, I sent the film off to Kodak and I just took the prints Kodak gave. I didn’t agonise over colour correction. I got the prints back and I pasted them on the wall and they were put up in a grid - which hadn’t been seen at the time - three rows high, around three walls of a small room.

The response has changed dramatically over the years but when I first showed it it really violated every rule of art photography regarding presentation and content. These were photographs of meals, of beds, of television sets. And the composition was as I said, like seeing and so often the subject was placed in the middle of the picture.

How did you feel when people criticised it – did you have any self doubt or were you headstrong about it?

I was headstrong about it. I didn’t like getting bad criticism but it didn’t cause me to doubt what I was doing. I had an absolutely scathing review in the Village Voice that I now have on my website. Actually it was not just scathing, it was vitriolic.

But on the other hand there were people who liked it. The people at the gallery liked it. Weston Neff, who was the photography curator at the Met bought the set. I only sold it as a complete set I never sold it as individual prints. So if you wanted American Surfaces you bought 200 prints. And he bought it and then gave it to the Met for their permanent collection.

Many, many years later, decades later, Nan Goldin told me that when she was a student she went to the show and what an impression it left on her. So there are some people who appreciated it but as I said it violated just about every rule of art photography.

Were you aware you were 'breaking the rules'?

Grammar has laws and it has rules. And the relationship of subject to predicate is a law. But not ending a sentence with a preposition is a rule. You can end it with a preposition. In fact, Shakespeare did! So there’s a difference between laws and rules. There are compositional rules that were as irrelevant to vision as the rule of not ending the sentence with a preposition is to writing.

And then you recreated the show for your 2017 MoMA retrospective

Yes, the prints were printed at exactly the same size, they were shown in a grid and pasted on the wall the same way as the original 1972 show. (When the show came down the prints had to be destroyed because peeling them off the wall tore the print.)

And when I would look at people’s Instagram feeds who’d visited the show the most posted pictures on people’s feeds were pictures of American Surfaces.

So people seeing the pictures today resonates, I think largely because of the kind of work that is done on Instagram, in an entirely different way. I’m not saying my work influenced Instagram because I don’t think there’s any link, but I would say that my work influenced art photographers who worked in the snapshot aesthetic because there is a chain of transmission.

There’s a chain of transmission to me. I looked at Walker Evans, and he had a profound impact on me. And Walker Evans had looked at (Eugene) Atget and (Mathew) Brady and they had had an impact on him. I know my work has influenced Nan Goldin and hers has influenced a whole generation of other people.

People come to a similar place or understanding on their own. I don’t think the vast majority of people who are posting on Instagram who are taking pictures of their food have not only never seen my work but have never seen anyone influenced by my work.

But you must have thought about the link, so what’s your theory?

I think it’s because there is a different kind of self awareness that I see on Instagram and it’s hard to generalise because there are a hundred million users and people do it for incredibly different reasons and there are so many different communities. There is even a house rabbit community!

There are all these different things but the kind of typical, slightly diaristic, Instagram user I think I just wonder if it has something to do with the way pictures look on a phone. Because there’s a similarity between that and a view camera.

You don’t look through a view camera the way you look through a 35mm camera. It’s not an extension of your eye. You look at a ground glass and so you’re always at least unconsciously aware that you’re not seeing the world, you’re seeing an image and that’s sort of the same when you’re taking a picture with an iPad or a phone.

You’re not looking through it, you’re holding it away from your face and you’re looking at an image you’re producing on it. And you move it over a little and the image changes. And I wonder if that leads to a different kind of self-awareness. I see these pictures of food, or a hand holding out an ice cream cone, or someone photographing their painted nails or even pictures of someone holding the steering wheel – a dangerous picture that occasionally I used to come to myself! Or looking down with your shoes in the picture rather than avoiding yourself and so there is a self-awareness that this is a photograph this is not the world. And I’m aware I’m making a photograph.

Have you ever been tempted to go back and do it again. Or do you do that in your mind?

The closest I get I would say is my Instagram practice. I do drive across country but they tend to be fairly fast trips. I’ll stop in one place and maybe get out and take a few pictures for Instagram. I’m not interested exactly and going back and redoing one of my long photographing trips. I feel I’ve done it.

There are people who are doing this with Uncommon Places, and going back to the places I photographed in that book, because all the pictures are identified geographically, and yes they find that the world has changed in some places – that is not totally surprising. So I’m less interested in whether it’s changed or not changed and I’m more interested in the experience of discovery and for me to go back and redo something is not that same kind of discovery.

One thing that has most definitely changed is William Eagleston driving along with what very much looks like a tumbler of whisky in his hand!

I’m sure people still drink and drive they may not want to be photographed doing that though!

What do you remember of that trip?

Very little. I went down to Memphis and we drove to New Orleans together. We went through Greenwood, Mississipi where he had grown up to visit his grandmother and spent a day in Greenwood and then went on to New Orleans and spent a couple of days there. Of which I have no memory what so ever! I think that’s what that was!

Look out for the third and final part of our Stephen Shore interview next week. For now head into the store and get your copy of our newly updated edition of American Surfaces.