The dangerous chemicals that could have killed Lynda Benglis

The US sculptor’s work with carcinogenic rubbers and foams drew attention to the interplay between the natural and unnatural world

The sculptor Lynda Benglis started water-skiing aged 13; in our new book, she recalls skimming over the local rivers and lakes of southern Louisiana. “They were polluted with oil slicks,” she says.

Both those landscapes and that pollution remained with her, informing her work as one of the world’s leading contemporary sculptors. “I’ve always been conscious of spoiling the environment,” says Benglis, who was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana in 1941, “because it was so pristine when I was young, but we’re in the process of cremating the world.”

Benglis’s own part in that polluting process dates back to the 1960s, when she drew on the work of American abstract painters such as Jackson Pollock (who was known for laying his canvases on the floor), and created works directly onto her studio floor. As the artist tells the curator Andrew Bonacina in our new Contemporary Artist Series monograph, she spilled a little of the wax she was applying to her picture onto her studio floor, “and that gave me the idea of finding a way to remove the frame or armature entirely and work directly on the floor.”

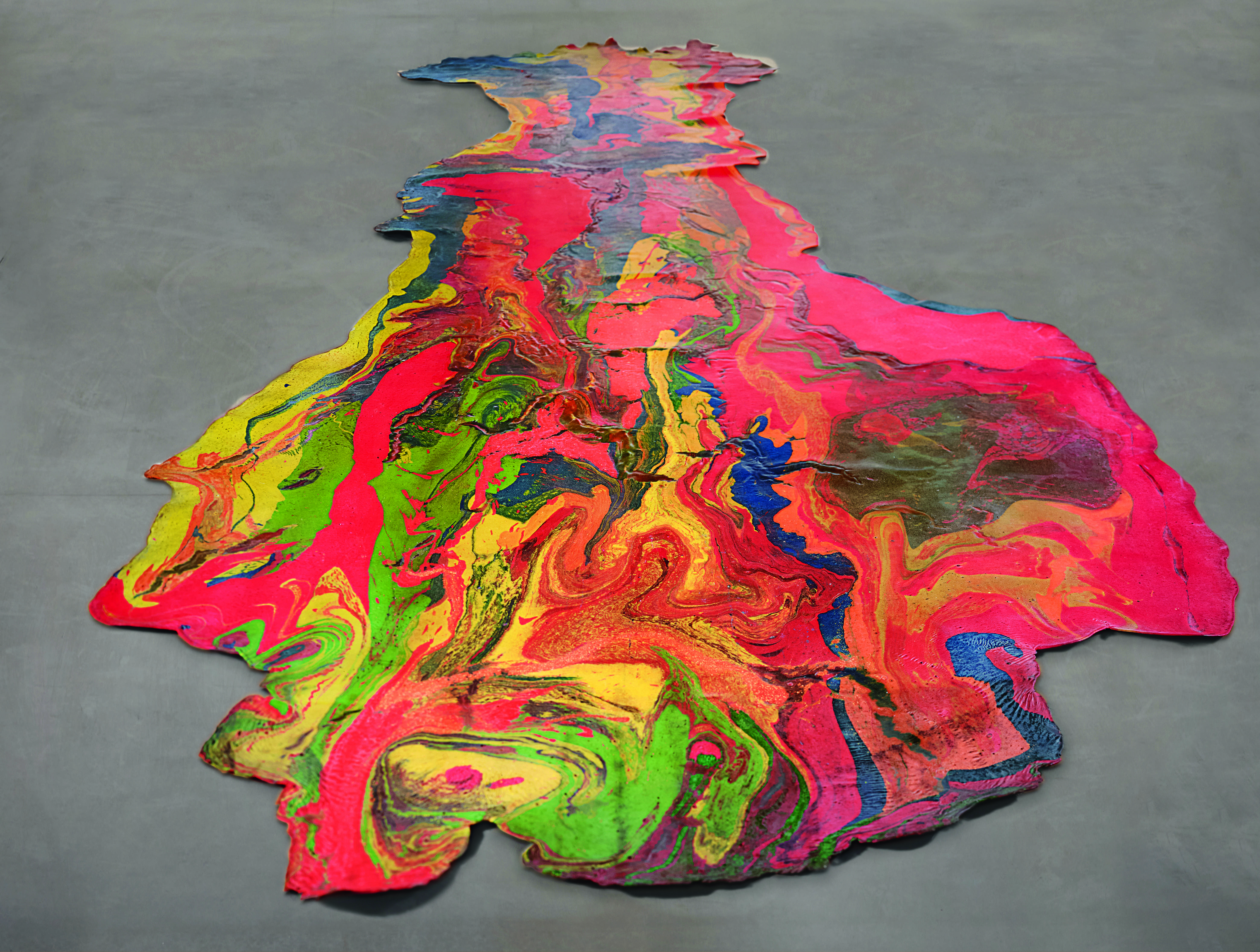

Lynda Benglis, Dallas, 1970. Pigmented polyurethane foam. 2022 Lynda Benglis / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Unfortunately, wax didn’t suit this process; for one, it was hard to remove once it was set. Benglis realised that she "needed to find something that would allow me to create a painting on the floor and then to be able to pull it up."

So she turned to the telephone directory. "I found a rubber consultant who had been a consultant during the war," she says. "He had a tiny lab, just two people, an amazing secretary who was a chemist and she ran everything. I got the best products from him. I used to tell him exactly what I wanted and he’d make it for me. So I was very lucky to be able to have my own little factory, shipping me things to Germany or museums all over the country when I needed it."

Benglis delighted in these modern materials, throwing rubbers and foams around her studio, pouring them onto frames, and wowing both in the gallery system and the chemicals industry with the results.

In 1970, the artist was featured in Life Magazine, and also put on the cover of Rubber Developments, the magazine for the US Rubber Bureau. "I liked the fact that what I was doing wasn’t just interesting to the art world," she says. "I think people really responded to the energy of it."

Unfortunately, all this vitality brought with it a fair share of morbidity. As Benglis says in her new book, both that rubber consultant and his colleagues “all died of cancer because they were working with carcinogenic materials.”

Lynda Benglis in her New Mexico Studio, 2015. Photo by Paul O'Connor

Benglis herself suffered from allergies, so wore a mask whenever she worked with these materials. This precaution, she believes, saved her. Though the ultimate turn of events were tragic, the sculptor still stands by those lively works with life-threatening implications.

Today, she works with less polluting products, yet she asserts in her new book that it “was interesting to me that these were toxic chemicals, because I was calling attention to the material itself. I was also interested in how common they were. These rubbers and latexes can be found in everything from the pillows we sleep on to the inner tubes of bicycle tyres. You always need the organic with the chemical; they remain constantly in motion. Things like that interested me – the fact that we were making all these things that are both natural and unnatural in order to function, in order to explore, in order for the world to work. I was interested in how to take these everyday materials and transform them into something else. And there was something political in this. I wanted it to draw attention to these realities."

Lynda Benglis

To see more of those works, and to better understand this important artist, order a copy of our Lynda Benglis book here.