The French Collection and the liberty of Faith Ringgold

In paying tribute to the artists of pre-war Europe, Ringgold also asserted her own creative freedoms

In 1961, Faith Ringgold first visited Paris. Though Ringgold was in her early thirties, she didn’t travel alone. As her daughter Michele Wallace writes in our new book, Faith Ringgold: American People, “she was accompanied by my sister and me as children, with Momma Jones (Faith’s mother) as built-in babysitter.”

The trip took place two years after Ringgold had received her master’s degree in art education at the City College of New York, and was undertaken with one goal in mind: “to figure out whether and/or how she could become an artist,” writes Wallace. “Much delay related to being a working mother ensued.”

Those struggles, ambitions, frustrations and fantasies were expressed three decades later, when Ringgold created one of her most important narrative quilt series, the French Collection. In our new book, the scholar and curator Bridget R. Cooks describes these works as a “a twelve-piece series in which Ringgold takes on the field of art history and its colonial partner, the museum, as its subject. In his essay about the series in the catalogue of the New Museum exhibition ‘Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold’s French Collection and Other Story Quilts, art historian Richard J. Powell explains the artist’s institutional critique: ‘The truths Faith Ringgold visually plies us with are (1) that women and men of African descent significantly figure in matters of art and art history, and (2) that audiences are capable of embracing not only an elitist, museum-sanctioned ‘high art’ but also a ‘people’s art’ that knows no class boundaries or social distinctions.’”

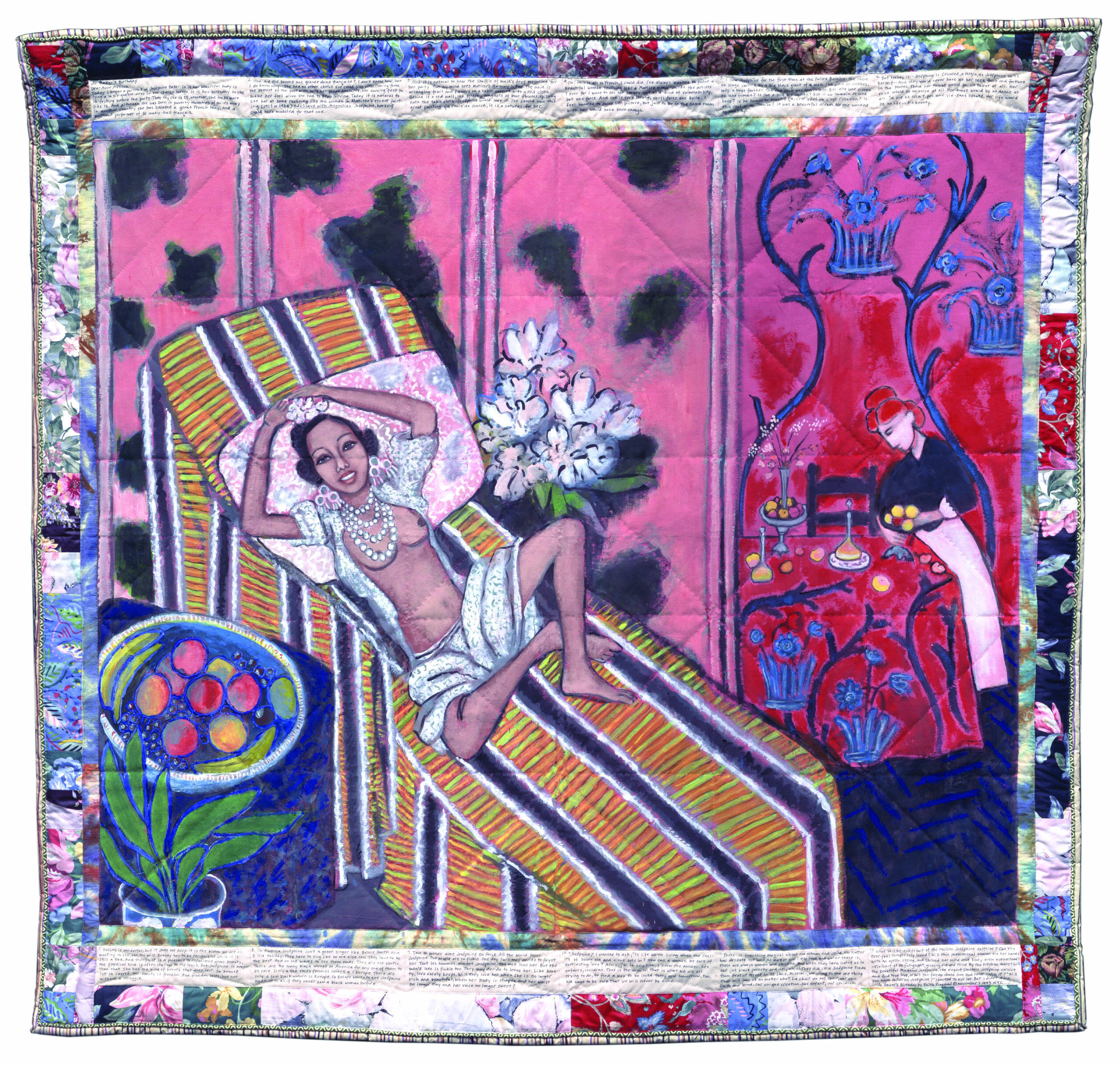

Faith Ringgold, Matisse's Model: The French Collection Part I, #5, 1991. Acrylic on canvas with printed and tie-dyed pieced fabric and ink. Baltimore Museum of Art; Frederick R. Weisman Contemporary Art Acquisitions Endowment. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2021

How does Ringgold tackle these subjects? “Through the invention of Willia Marie Simone, the protagonist of the series.” Cooks goes on. “A young black woman who travels to Europe to become an artist, Willia Marie is a participant in the development of modernism; she guides the viewer through Ringgold’s revisionist art history. It is through Willia Marie’s encounters that Ringgold rejects the enforced invisibility of black women in art history.”

The character, which Wallace says was partly partly based on Faith herself and partly based on her mother, “ travels to France in 1920 at the age of sixteen and marries a wealthy white American expatriate who dies soon after giving her two children, Marlena and Pierrot.”

“Willia Marie’s Aunt Melissa financed her initial trip to France with a gift of $500, on the supposition that it would be more likely for her as a black woman in the 1920s to become a successful artist in France than in the United States,” Wallace expands. “Getting married and having two babies was a detour in the opposite direction. And yet, still determined to become an artist, and with her husband’s death having left her independently wealthy, she decides the best way to proceed is to send the children to Atlanta to be raised by her Aunt Melissa, leaving her free to pursue her career.”

Faith Ringgold, Picasso's Studio: The French Collection Part I, #7, 1991. Acrylic on canvas with printed and tie-dyed pieced fabric and ink. Worcester Art Museum; Charlotte E. Buffington Fund. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2021.

In this odd, counterfactual setting, Ringgold introduces Willia Marie to key figures within the late 19th century and early 20th century French art world, including Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and Claude Monet. Yet Ringgold doesn’t faithfully copy art history. In her quilt, The Picnic at Giverny, she offers her take on Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’ herbe, depicting clothed women, beside a nude male artist – Picasso in this instance. In Dancing at the Louvre, Willia Marie’s party dances beside Renaissance masterpieces, uniting supposedly ‘high’ and ‘low’ forms. In Baker’s Birthday, Ringgold places the African-American star at the centre of a work that references Manet’s Olympia and Matisse’s Red Room. “In the process, the Black Jo Baker becomes the Olympia figure, and the white woman in the background is configured as her servant, reversing the racial roles of the Manet painting,” writes Wallace. And in Picasso’s Studio, Ringgold casts her avatar as a model for Picasso’s masterpiece, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and in so doing, shifts the emphasis in Picasso’s work, referencing the clear debt he owed to African art.

Faith Ringgold, Jo Baker's Bananas: The American Collection #4, 1997. Acrylic on canvas with painted and pieced fabric; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC, Purchased with funds donated by the Estate of Barbara Bingham Moore, Olga V. Hargis Family Trusts, and the Members'; Acquisition Fund. Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2021

“Willia Marie hears the whispers of the masks and paintings collected in Picasso’s studio while she models for him during his Cubist period,” writes Cooks. “Impatient and bored, she also hears the voice of her aunt saying, “You was an artist’s model years before you was ever born, thousands of miles from here in Africa somewhere. Only you’all wasn’t called artist and model. It was natural that your beauty would be reproduced on walls and plates and sculptures made of your beautiful black face and body.”

Viewed together, the French Collection can be read as a fantastical escape, or a dash through the demi-monde of pre-War Paris. Yet perhaps the most cogent response is to view the works as a statement of intent, from a woman who adored art, but sought to become an artist on her own terms.

Cook quotes from a letter included in the texts of the French Collection, from Willia Marie ot her aunt, which is sprinkled with newly acquired French words. “You asked me once why I wanted to become an artist and I said I didn’t know,” the letter says. “Well I know now. It is because it’s the only way I know of feeling free. My art is my freedom to say what I please. N’importe what color you are, you can do what you want avec ton art, with your art. They may not like it, or buy it, or even let you show it; but they can’t stop you from doing it.”

Faith Ringgold: American People

For a better understanding of the work this important artist created, order a copy of Faith Ringgold: American People here.