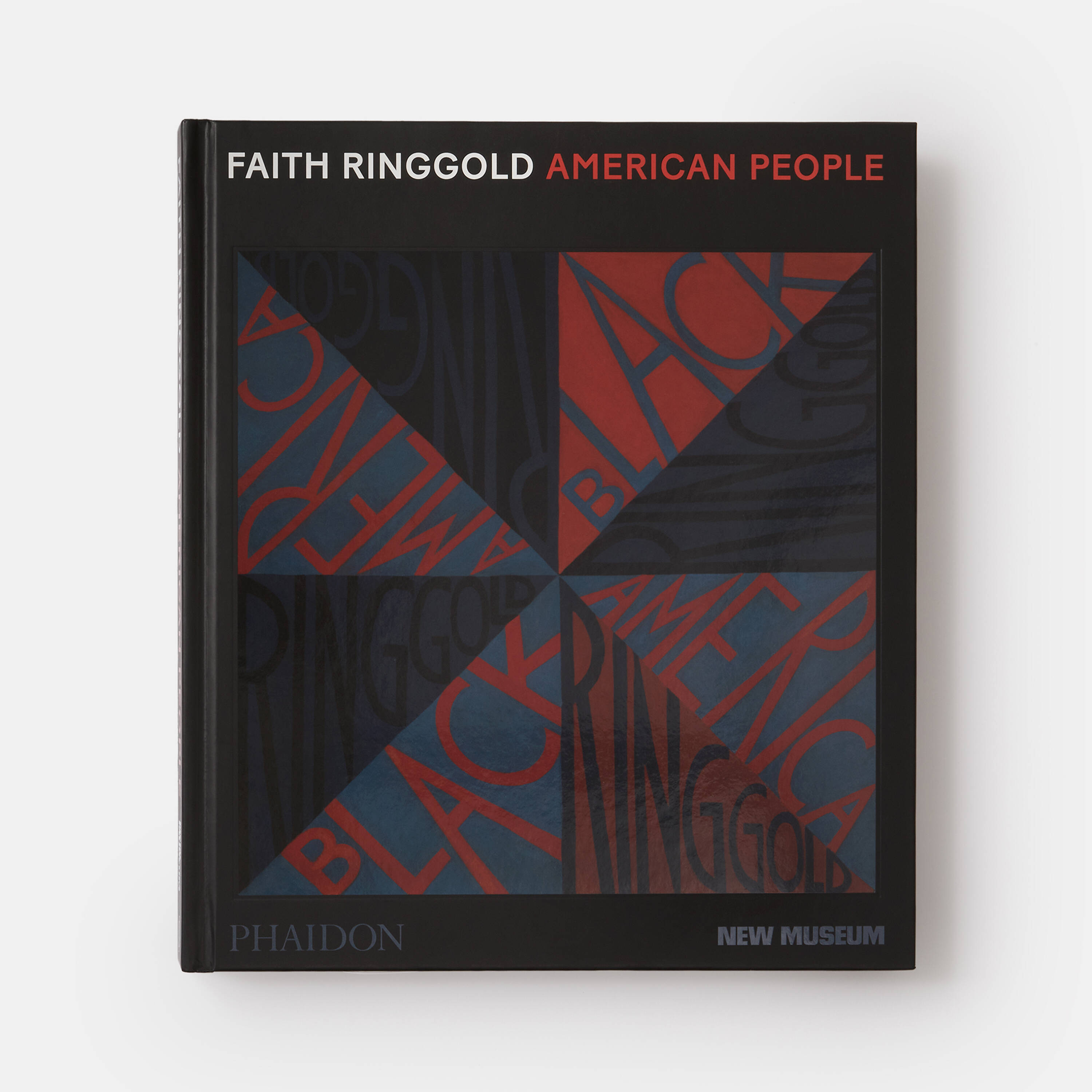

The life of Die, Faith Ringgold’s absolutely startling masterpiece

We trace the development of the painter’s 1967 work, via Picasso, MoMA and the Civil Rights Movement

When Faith Ringgold took her daughters to the Museum of Modern Art back in the 1960s, there was one work in particular that they enjoyed: Pablo Picasso’s 1937 painting, Guernica. This picture, depicting the horror of the aerial bombardment of this Basque town during the Spanish Civil War, was, Ringgold said in a 2020 interview, “the painting we used to go looking for.”

It left a lasting impression. In Faith Ringgold: American People, our new book to accompany the artist's 2022 retrospective at the New Museum, the British curator Mark Godfrey argues that Picasso’s piece "gave Ringgold ideas about iconography (figures holding babies, screaming mouths), but more importantly, Guernica showed her that the most effective way to protest and memorialise violence and its victims was to take absolute care with composition."

It was a painting that remained with the American artist, as she created perhaps her best-known work, American People Series #20: Die. This 1967 oil-on-canvas painting is the final work in her American People series, a set of pictures that Ringgold began in 1963, when the overriding tone of US race relations was one of nonviolent protest, rather than outright bloodshed.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #1: Between Friends, 1963. Oil on canvas, 40 x 24 in (101.6 x 61 cm). Collection Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York; Museum purchase with funds from the Roy R. Neuberger Endowment Fund and Friends of the Neuberger Museum of Art. © Faith Ringgold / ARS, NY and DACS, London, courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2021

“It was the year Martin Luther King Jr. stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and described his dream that, one day soon, ‘the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood’,” writes Godfrey. “The civil rights movement was achieving some of its goals, and in some ways King’s strategy of nonviolent protest seemed to be working.”

Despite this, the earliest works in Ringgold’s series aren't very optimistic. “In the first painting, American People Series #1: Between Friends (1963), two women stand together—one is white; the other more than likely would have called herself a ‘Negro.’” writes Godfrey. “ The second painting in the series, For Members Only (1963), depicts a gang of six white men with grim expressions whose huddle forms a kind of wall excluding the presumed newcomer, who will not be let into this club on account of their race. For Members Only asks us to imagine a black figure positioned in the space of the viewer, and the series’ third painting works this way too. In Neighbours, also from 1963, a group of sullen-looking white folks (a grandma, a couple, and their son) seem nonplussed by—or indeed hostile to—the person who has moved in next door. So much for the table of brotherhood.”

Faith Ringgold, Early Works #25: Self-Portrait, 1965. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in (127 x 101.6 cm)

This uneasy mood in Ringgold’s work did not exactly lighten over the following four years, though interest in her painting grew. In 1967, Robert Newman, director of the Spectrum Gallery on 57th Street in Manhattan invited Ringgold to show these works, and, in the months preceding their exhibition, to use the gallery as her studio to complete further paintings in the series.

“He knew that Ringgold could push her subject matter further and address more explicitly the discord between the races, a direction the artist was already contemplating,” reasons Godfrey. “In Ringgold’s memoir, she writes, ‘Robert wanted me to depict everything that was happening in America—the sixties and the decade’s tumultuous thrusts for freedom. Maybe I would have done this anyway, but it was very comforting to have someone suggest something that is exactly what you should be doing.’”

The artist painted three further pictures, concluding with Die, in response to the changing times. Godfrey lists just a few of the events that altered the tenor of American racial politics in the years preceeding ‘67: “Weeks after King’s [1963] speech, four girls were murdered in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Riots and protests spread across Harlem in 1964; Malcolm X was assassinated in February 1965; the Watts Rebellion shook Los Angeles in August of the same year; and during the Long Hot Summer of 1967 when Ringgold was making the paintings, forty-three people died in race-related uprisings in Detroit, and twenty-six much closer by in Newark, New Jersey.”

This shocking register of violence clearly influenced Ringgold. “I was just trying to read the times, and to me everyone was falling down,” Ringgold told the New York Times in 2020. “And if it upsets people that’s because I want them to be upset.”

However, Die, unlike Guernica, should not be read as the depiction of one, single event. Stylistically, its appeal is broader. “Contours were simplified; faces and limbs were depicted with blocks of colour rather than in gradated shades,” writes Godfrey, “there was no attempt to represent deep space or shadow; clothing was uniform; each ‘white man’ and ‘black man’ in Die has very similar features to one another.”

“Ringgold’s 'Super Realism,' as she later called her style, shares many characteristics with heraldry and sign-painting and, indeed, communicates in a similar manner. It allows her scenes to read symbolically rather than as records of individuals or specific events,” the curator concludes. “Had viewers felt they were seeing depictions of specific people, their own ability to connect would have been much more limited.”

The figures’ clothing is quotidian too. Dressed formally in the middle-class clothes of the day enabled Ringgold to express the point, as she put it in a 2020 interview, “that these people are not the people who are normally in the street fighting. This is a spontaneous street riot that could happen anywhere."

Godfrey detects influence from popular mid-century American artists in this work also. “Jackson Pollock’s drips of paint become splatters of blood, the chequered background recalls the predominance of grid painting in modernism, and the slight variations in greys recall the work of Ad Reinhardt,” he writes.

The curator also picks out Guernica’s direct influence on Die. “Ringgold also used limbs as lines to tie everything together, and, as if to recognize how many compositional lessons she gleaned from Guernica,” Godfrey writes. “She quoted parts of it—for instance, the bent knee of the black woman to the far right references the bent knee of the woman in the bottom right corner of Picasso’s painting, and the white man whose head touches the bottom edge of the painting is in almost exactly the same position as the body lying in Guernica with arms similarly outstretched.”

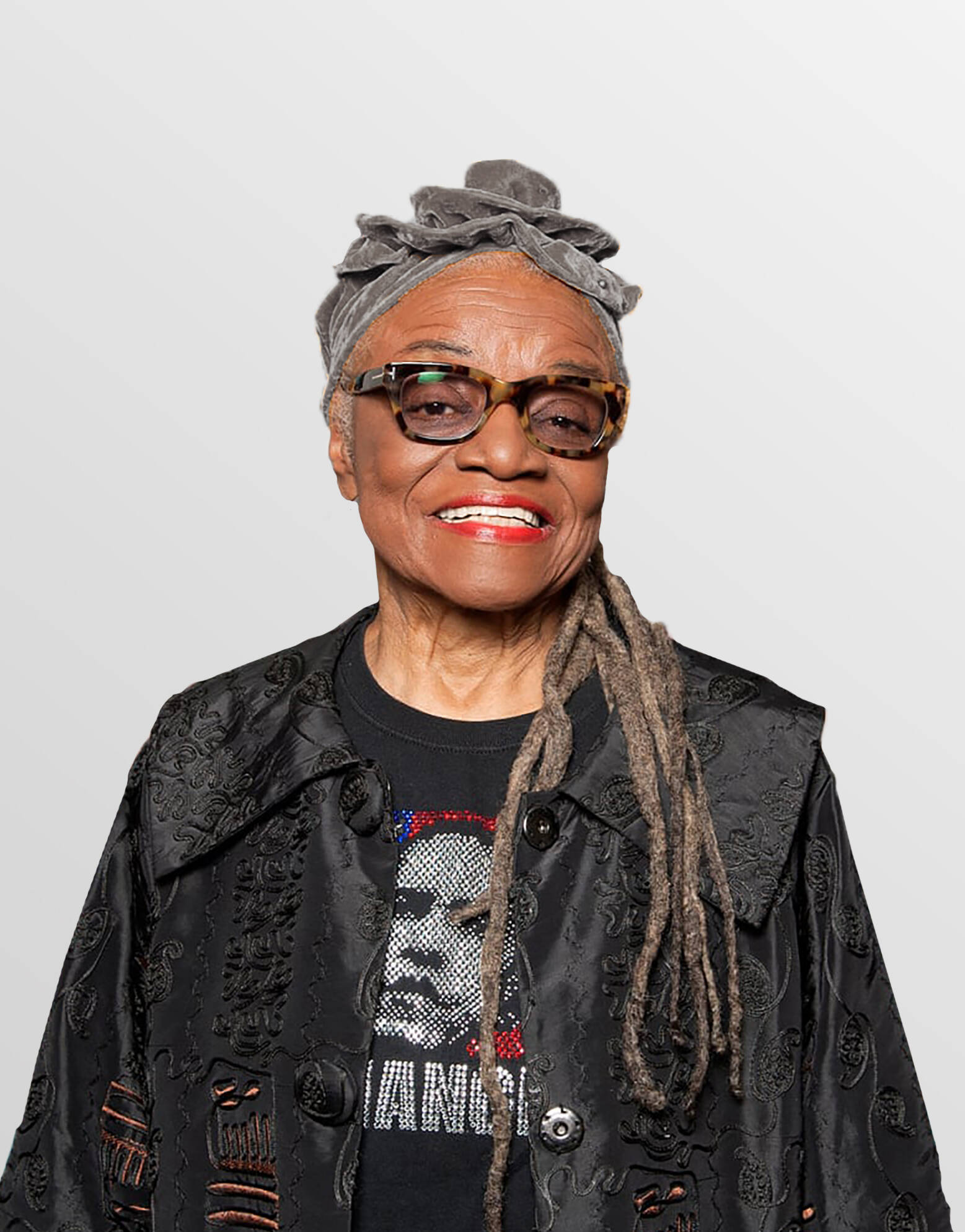

Faith Ringgold. Courtesy ACA Galleries, NY

And, while Guernica presaged the horrors of World War II, Die hints at a brighter future. Focusing on the infants in the painting, Godfrey writes, “while King’s dream of little black girls joining hands with little white boys makes way for Die’s nightmare of frightened children clutching each other, at least they have found one another.”

He doesn’t view Die as a gleeful vision of American collapse, but instead sees this painting, and Ringold’s wider work as hopeful. “Rather than advocating for revolution and the outright replacement of white institutions, her vision as an artist was one of recognition, representation, and reform,” he writes, “recognize what was happening on the streets, give it representation, and reform American art and attitudes.”

That reformation has been quite literal in Die’s case. When MoMA reopened in 2019 following a $450-million, 47,000-square-foot expansion, Die was hung beside Picasso’s 1907 masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, in a move that Holland Cotter, writing in the New York Times, described as “a stroke of curatorial genius.”

Die as it appears in Faith Ringgold: American People

The public appears to agree. The following year Ann Temkin, MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture, told the Times that Die had become a must-see for many visitors, just as Guernica had been for Ringgold and her family many years before. “Certain works become visitor favourites over a long period of time,” Temkin was quoted as saying, “but it’s rare when a painting instantly becomes one.” That’s testament, perhaps, to Die’s immortality. To better understand this powerful, important work and its creator, order a copy of Faith Ringgold: American People here.