How Adrián Villar Rojas 'threw a dinner party' on the Met roof

The Theater of Disappearance featured artefacts from the Met’s collection, spanning thousands of years

Three years go, on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum in New York, Adrián Villar Rojas created a sculptural installation that looked quite a bit like a fine-art banquet. As with a lot of good parties, there was a mixture of familiar faces and less well-known ones.

Called The Theater of Disappearance, it was a machine-made homage to the Met’s own incredible trove of objects below. “Along with tables and chairs, food and cutlery and other objects of little or no value – as well as life-size figures – a hundred rare and valuable artefacts from the Met’s collection spanning thousands of years of artistic production over several continents and cultures were all scanned,” explains museum director and author Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in our new book on the artist. “Fused together and replicated using robotic milling, they were then rendered uniform with black or white paint and later coated with a thin layer of dust.”

Villar Rojas, whom the New York Times described as having “a sci-fi writer’s imagination and an ecologist’s anxieties,” wasn’t simply paying tribute to the collection held in the floors below.

His exhibition, which was displayed through the summer of 2017, before its name was recycled for subsequent exhibitions in California, Germany and Greece, was a protest work too. He was inspired in part by a 1970 photograph of young Black Panthers protesting outside a New Haven courthouse where Bobby Seale, co-founder of the party, was standing trial for murder. “They’re holding their fists in the air while sitting on the shoulders of a huge statue on the steps of this white, neoclassical building,” explains the artist in our new book.

As the artist took possession of his own bit of public space within another white, neoclassical building, the parallels became quite apparent. “During the research process, the extreme hierarchical and departmental structure of the museum immediately manifested itself, generating both obstructions and an opportunity to reflect on what lies beneath the surface of so-called encyclopedic institutions like this one,” Villar Rojas tells Hans Ulrich Obrist in our new book.

“I was looking for alternative vertices in the departments’ official history, many of which copied the model of eighteenth-century, mostly European museology, but also in the demarcation of the departments themselves,” he went on.

“I looked into the forgotten peripheries: Cyprus in Greco Roman, the Amerindian woman in what’s perversely named the American Wing, but primarily includes colonial and early United States Republic artefacts. The American Wing could be seen as the subconscious of the museum, which betrays a series of meta-postcolonial interpretations: its entrance is a vast atrium filled with neoclassical sculptures in front of a reconstructed façade from a Wall Street bank, and in front of that venerated and preserved façade one encounters a nineteenth-century white marble sculpture called Mexican Girl Dying, possibly the most profound expression of culture within the Met. Being someone from the South of America, to see all these elements in a clear state of conflict constituted a very visceral experience.”

Much of that visceral quality comes across to the viewer, and yet The Theater of Disappearance wasn’t simply a critical piece. As the artist explains in our book: “A visible layer of what looks like dust was then applied to each sculpture, accumulating in its nooks and crevices. This uniformity generated a sense of ambiguity both regarding the origins of the Met artefacts and the people, obliterating and questioning all the cultural readings that are carried into our everyday constructions.”

Where’s the theatre here? And what has disappeared? In Christov-Bakargiev’s view, the work’s machine-made quality suggests that the Met’s Imperial revelry might be in the past.

“We are living in a cold, detached, high-tech environment, the realm of smart technology, a future world of digital materiality, the internet of things, where little space is left for any chance of life to flourish,” she writes. “We are in the Museum, we are in a world after art, in a time after time.”

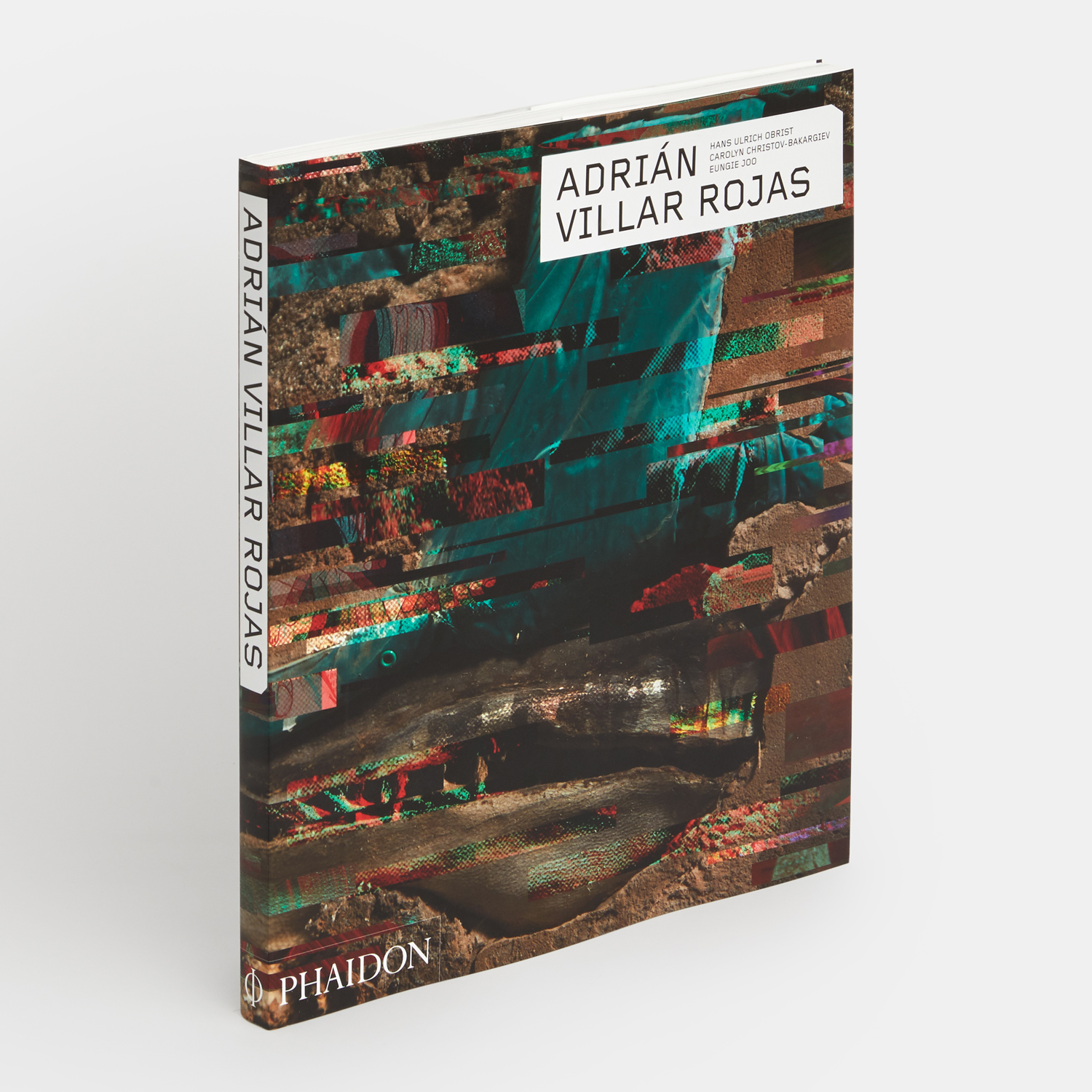

To read more from her and the artist, and to see many more images of Villa-Rojas’s work, order a copy of our new Contemporary Artist Series book here.