Treating serious subjects as ‘entertainment in disguise’ is a constant in the late Martin Parr’s body of work. In 2021, the photographer, said, ‘I’m creating entertainment, which has a serious message if you want to read into it, but I don’t expect to change anyone’s mind – I’m just showing them what they think they may know already.’

And yet throughout his work, Martin Parr displayed unwavering faith in the critical power of documentary photography, a genre he defended tirelessly, well beyond his own images. This documentary approach drew him, as Quentin Bajac, director of the Paris arts center Jeu de Paume, writes in our new book Global Warning, “to photograph the quirks of our era with a blend of apparent neutrality and clinical precision.”

In Parr’s work, congruity Bajac writes, “often arises from the contrast between the banality of his subjects and the methodical discipline of his photography – devoid of judgement, empathy or hostility. This does not, however, imply an absence of critical analysis; the analysis is merely carried out insidiously, indirectly, in a disguised or ‘hidden’ manner.”

Martin Parr, Blue Grotto, Capri, Italy, 2014. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Our new book Global Warning accompanies an exhibition at Jeu de Paume and was the last book the photographer worked on, with Bajac, shortly before his untimely death in December last year. Showcasing many of Parr’s most renowned images alongside rarely published hidden gems, Global Warning presents more than five decades of incisive visual commentary and places Parr’s vast body of work within the context of the global effect of mass consumption.

When discussing this exhibition and his critical approach to our post-industrial consumerism and lifestyle over the past fifty years, Bajac notes that Parr mentioned a ‘hidden agenda’. “What he meant,” Bajac writes, “was that, although he recognizes this obvious aspect of his work, the theme has developed gradually in a non-linear, unintentional, inexplicit and unpolitical manner. And if his perception is sharper today, it no doubt reflects an evolution in our thinking and our awareness of the issues that are raised in the images.”

Martin Parr, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France, 2012. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

In his introduction Bajac points out both his and Parr’s gradual realisation as to the main thrust of Parr’s vast body of work when viewed from the current moment.

“The way we look at the work has changed alongside the work itself. Across the globe, Martin Parr has shot countless photos of various abuses of the Western capitalistic lifestyle, which is greatly responsible for climate disruption. While he has surveyed the – at times artificial – overabundance in our society, he has never explored poverty or directly focused on the effects of climate change.”

Martin Parr, Kleine Scheidegg, Switzerland, 1994. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Martin Parr, Kleine Scheidegg, Switzerland, 1994. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

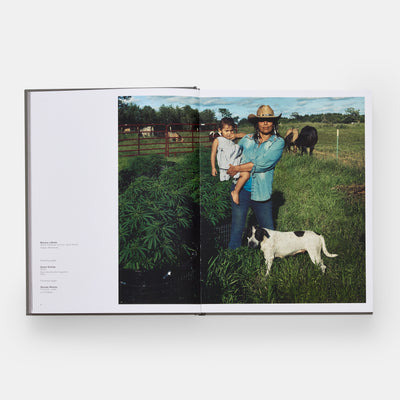

As Bajac notes in his introduction, in 2009, Parr was commissioned by Oxfam to visit Quang Tri province in Vietnam to make a series of full-length portraits of farmers who were losing their rice harvests to increasingly heavy floods. The assignment sparked a bit of a breakthrough for Parr, as he wrote on his blog that same year and reproduced in the new book.

“I can now see how nearly all the images that I have recently taken and produced are indirectly related to climate change. For example, my recent book entitled Luxury is an exploration of how the wealthy go about parading themselves at horse racing events, art fairs or fashion shows. I photograph wealth in the same spirit as has traditionally been associated with photographing poverty, an updated version of the ‘concerned photographer’ but disguised as entertainment.

For surely, what is the main indirect cause of our increasing carbon emissions, but the increasing wealth of our planet? Other recent subjects, such as an arms fair in the Middle East or tourism in Machu Picchu, all have a link to climate change. So from now on I am just interpreting the serious issue of climate change in as many creative and lateral ways [as] possible.”

Martin Parr, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2000. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Bajac argues that Parr knew that images can no longer change the world, but nevertheless, he “pursues a sort of unassuming activism, a ‘visual guerrilla warfare’ able to shatter the dominant representations – from adverts to family photo albums – feeding into an idealized collective imagination that tends to smooth out reality and make it more palatable. For Martin Parr – because ‘the tourist does not travel to things, but to images of things’ – the tourism industry is a prime target.”

In a 2019 interview Parr called tourism “a subject full of propaganda. All the travel pages in the newspapers make it look very attractive, but they would never want to show the issues or the problems with over-popularity in places like Barcelona and Venice. It just seemed like a natural thing to do, and I’ve been doing it ever since.”

Martin Parr, Tokyo, Japan, 1998. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

By the same token, Bajac writes in his appreciation of Parr’s work, ”we can claim that much of the series Common Sense, with its steady insistence on eating and drinking as primary forms of consumption, subverts the clichés of food photography: the food it shows is anything but appetizing. More broadly, Parr’s work on overconsumption – through a blunt, lurid depiction of a wide range of appetites and desires, social classes and cultures – pokes fun at the idealized and carefully staged images of advertising photography.

Martin Parr, Venice, Italy, 2005. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

We might even say that Parr’s approach rests on the invariable questioning of traditional photography genres. Thus the postcard, with its sleek aesthetics and stereotypes, is mocked in his photos of famous monuments, often shown in a (real or symbolic) lessened state – whether swarming with crowds, or through copies and reproductions of ‘authentic’ monuments, if the term even applies anymore.”

Martin Parr, Mumbai, India, 2018. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

“Through Parr’s lens, Machu Picchu contains little of the sacred and sublime; it becomes an accessory, a misty backdrop for the shapeless forms of international visitors, displaying incongruous attitudes often at odds with the setting. Similarly, a beach no longer provides a moment of escape and communion with nature, as advertised in tourist brochures.

And when it does remain ‘natural’ – which is by no means a given – it is merely a sandy extension of urban life, with the same social comportments and population density: we queue up to buy food, surf in a sea as dense with bodies as a subway platform and swim in water as congested as a public pool. For Parr, the beach is not a site of exotic escape, but a place of alienation.”

Martin Parr, Seagaia Ocean Dome, Miyazaki, Japan, 1996. Credit: © Martin Parr / Magnum Photos

Want to read more of Quentin Bajac's thoughts on Martin Parr's work? Global Warning features the full text plus four more insightful and contextual critiques of Parr’s work from Jean-François Staszak, Roberta Sassatelli, Violette Pouillard, and Adam Greenfield, experts in the fields of geography, sociology, wildlife conservation and urban design.

Showcasing many of Parr’s most renowned images alongside rarely published hidden gems, Global Warning presents more than five decades of incisive visual commentary. Martin may no longer be with us, but his legacy lives on.

Take a closer look at Global Warning.