Growing up in a strictly vegetarian household in Questelles village on Saint Vincent, a volcanic island in the Caribbean, Rawlston Williams was not allowed to taste many of the dishes his neighbors and friends enjoyed: fish, pork, beef, goat, lamb. But although these foods were out of reach for the young boy, they were never out of mind.

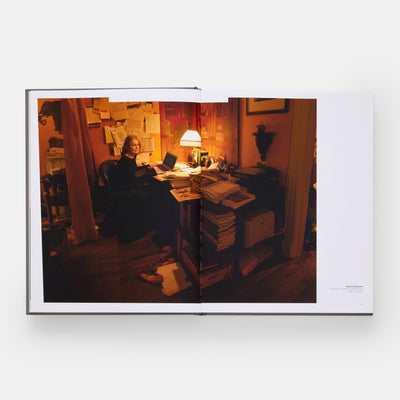

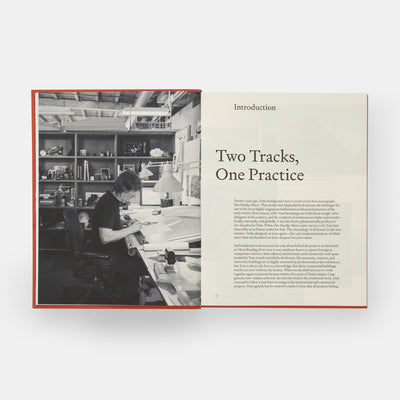

“My way of consuming them was through the air, through the aromas that filled our village. I could smell what my neighbors were cooking. I could tell what my best friend two houses down was having for dinner based on the scents that drifted through the breeze,” Rawlston (photographed above by © Cynthia Simpson) writes in the introduction to The Caribbean Cookbook.

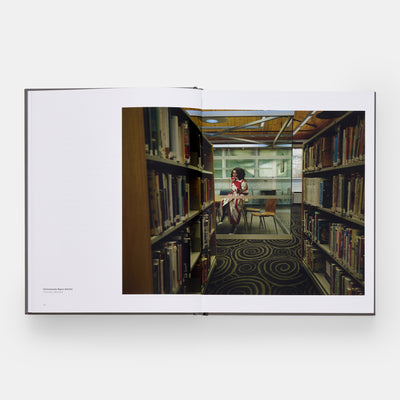

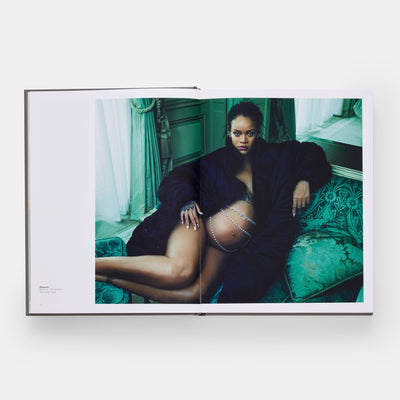

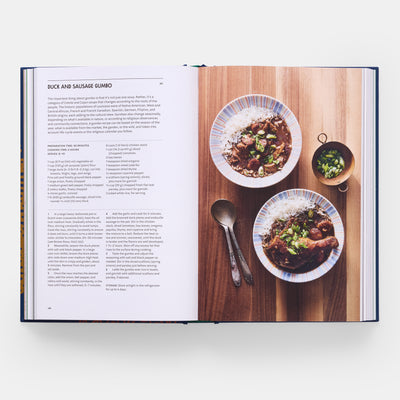

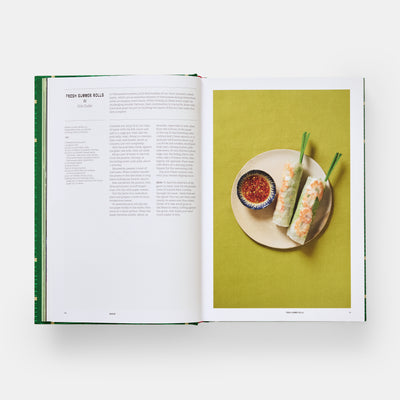

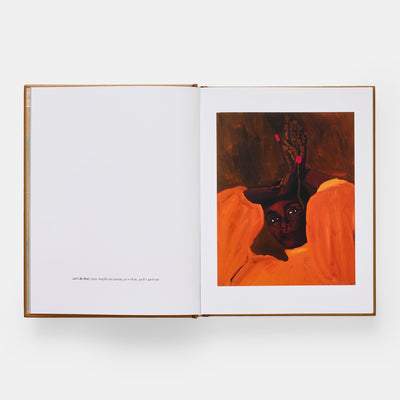

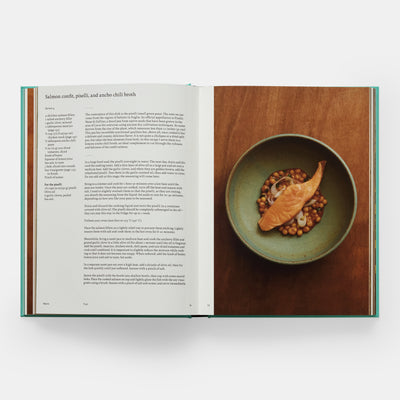

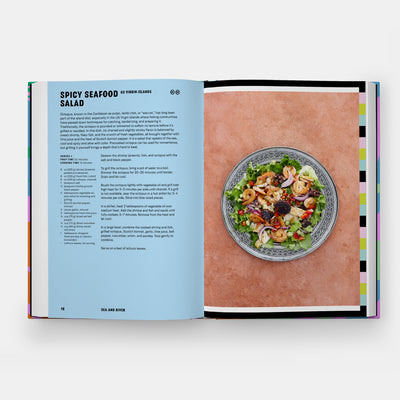

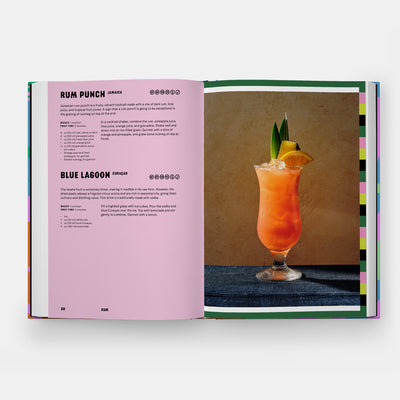

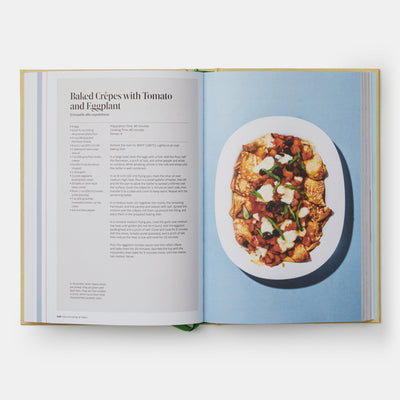

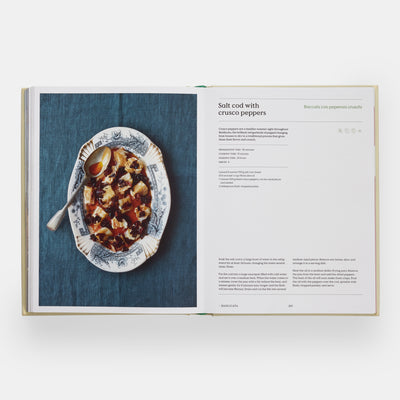

Seafood Creole. Photography: Nico Schinco

“My childhood was full of sensory experiences that shaped my connection to cooking. We had cows and goats in the yard, along with an abundance of fruit trees. My neighbor, Miss Julie Kelly, taught me a lot about traditional methods of food preparation without even realizing she was doing it. I helped her with chores, including making cocoa. She would parch the cacao in a large cauldron filled with sand over a wood-burning fire, using a rake to ensure the kernels toasted evenly. I helped her shell the cacao, grind it, and roll it into individual pieces, which she sold as part of her livelihood. It would then be used to make hot cocoa tea in the mornings.”

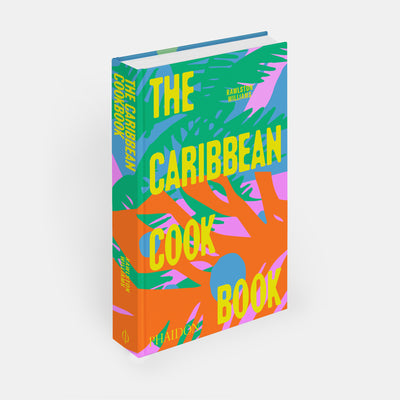

Rawlston has drawn upon those formative experiences and the significant expertise he’s accrued in the following years—he is a graduate of the French Culinary Institute and was for many years the chef-owner of a much-loved Caribbean restaurant called The Food Sermon in Brooklyn—for The Caribbean Cookbook, our fascinating trip through Caribbean cuisine.

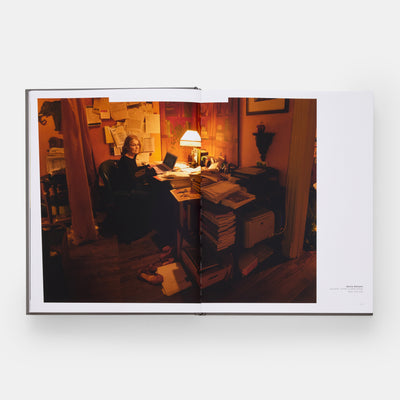

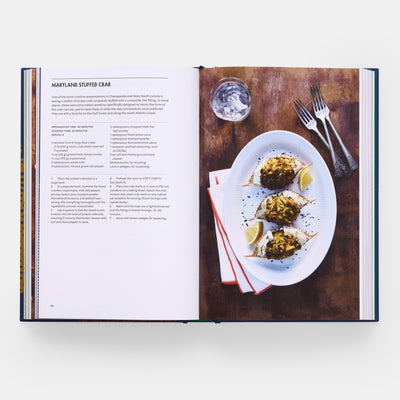

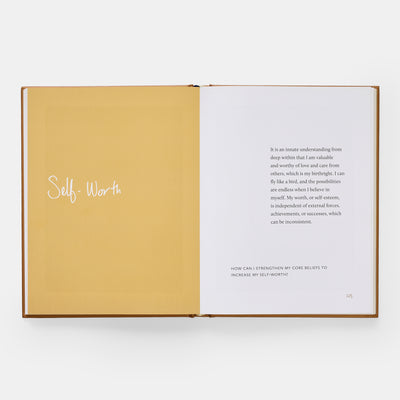

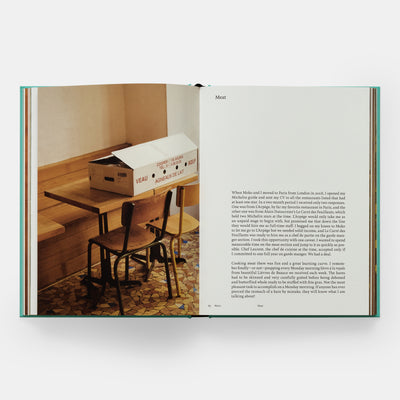

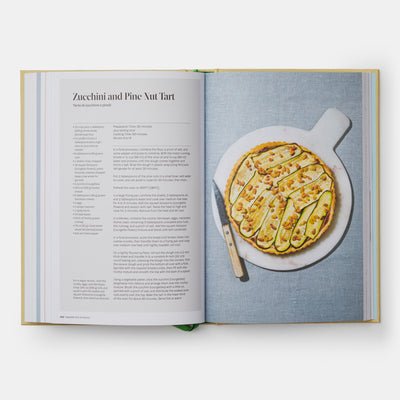

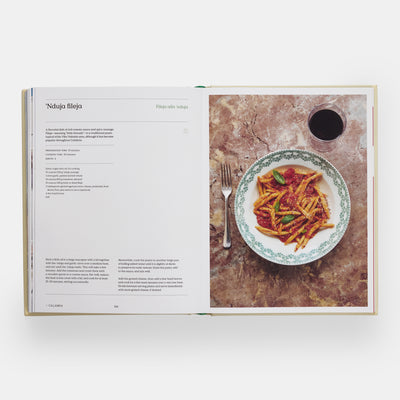

Tri Tri Fritters. Photography: Nico Schinco

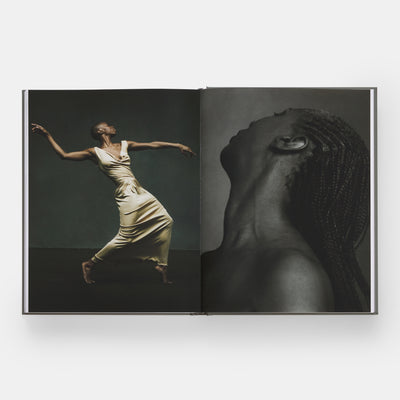

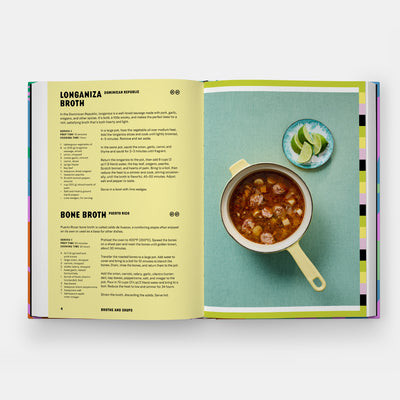

Williams explores and highlights the origins and influences of Caribbean cooking in the book, which features 400 recipes from across the region of 28 island nations and dependencies.

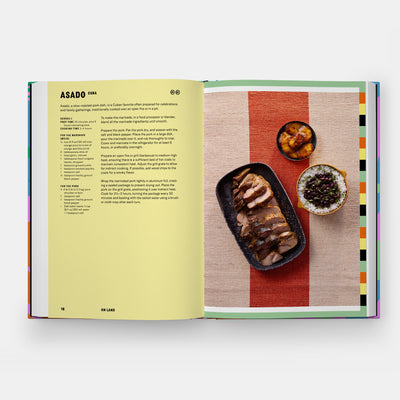

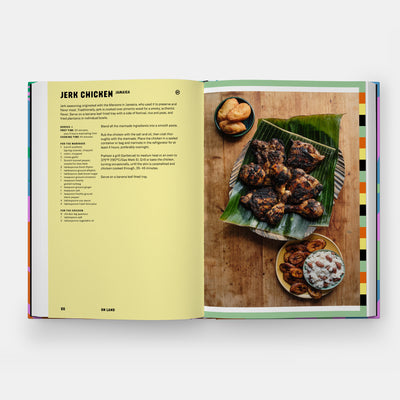

Each island reflects its own colonial history, cultural mix, and geography. French-speaking Martinique and Guadeloupe showcase a Creole cuisine heavy with French culinary traditions; while Spanish-speaking Cuba emphasizes sofrito bases, black beans, and slow-cooked pork. Jamaica has become synonymous with jerk seasoning and rum-rich cake, while Trinidad and Tobago, with its large Indian-descended population, highlights roti, and curries alongside African staples.

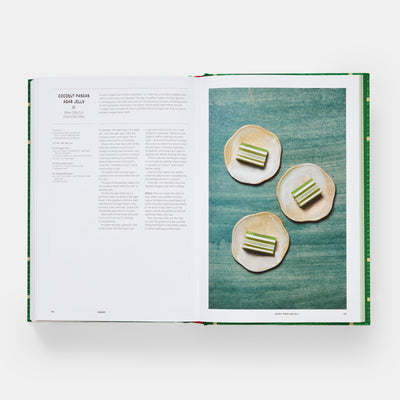

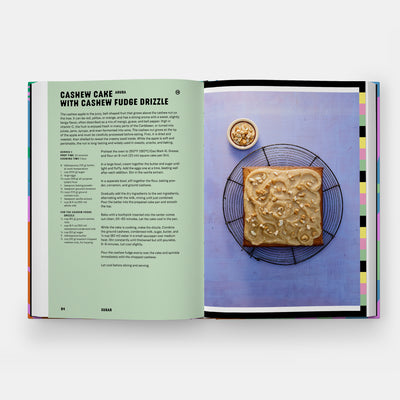

The tastes are synonymous with the region—citrus, nutmeg, coconut, pimento, and pineapple are some of the ingredients showcased throughout. Each chapter features at least one deep-dive essay from Williams into the culture, ingredients, and history surrounding this cuisine.

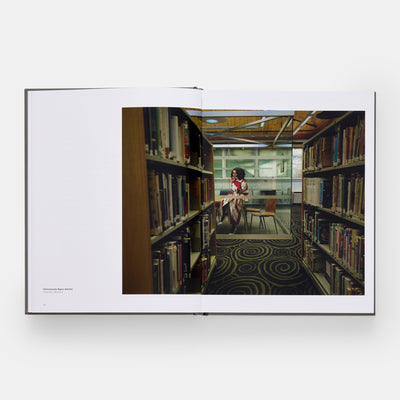

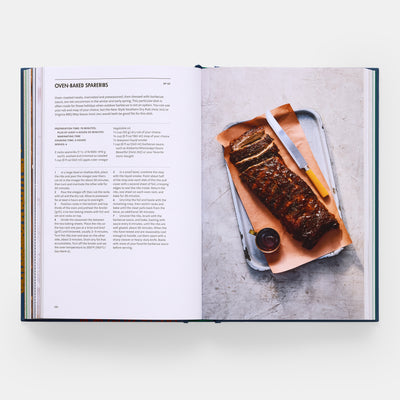

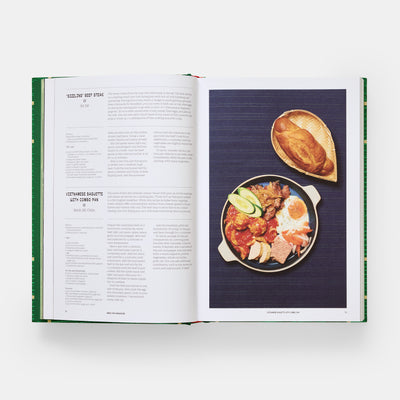

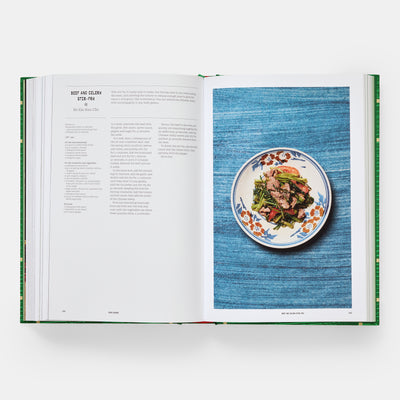

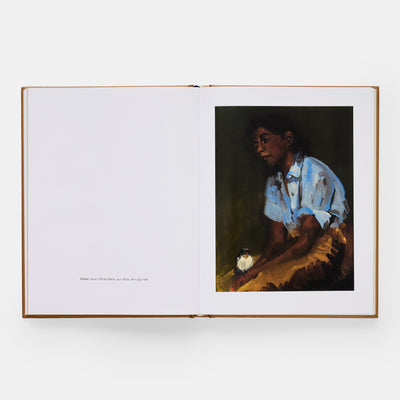

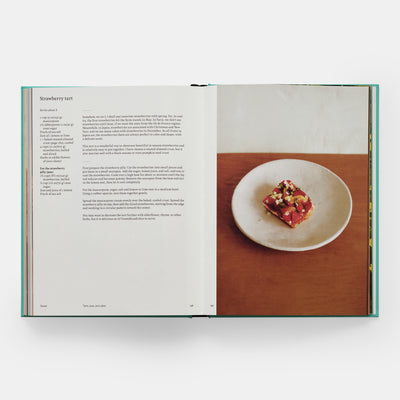

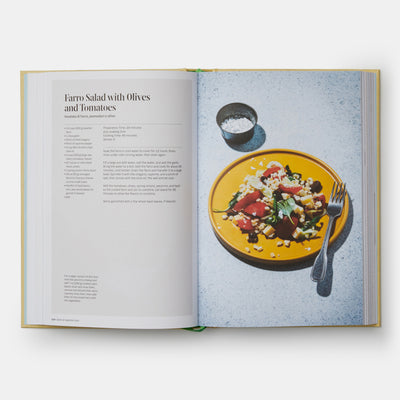

Pelau. Photography: Nico Schinco

Throughout, Rawlston’s presence and his own captivating story is to the fore. “I truly learned how to cook from my guardian, Gloria Farrell,” he writes. “She suffered from rheumatic fever and rheumatoid arthritis and spent a lot of time upstairs in bed. I was her arms and legs. She would yell ingredients down to me from her bedroom window, and I would stand below, listening carefully to her instructions. Then I would run into the kitchen, which was on the first floor at the back of the house, and get to work.”

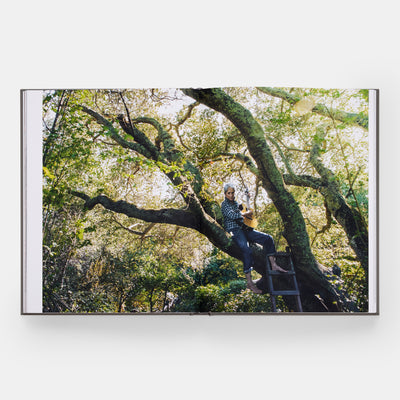

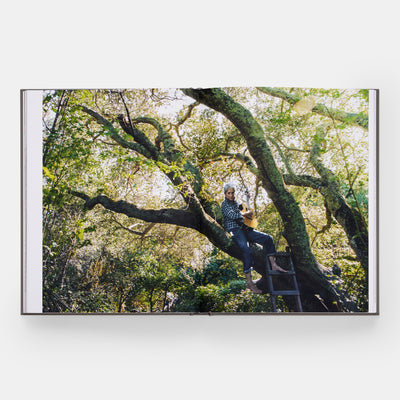

Photography: Rawlston Williams

“By the time I was seven years old, I was cooking full meals. Fridays, for me, became synonymous with the smell of freshly baked bread. As Seventh—day Adventists, we prepared everything for the Sabbath ahead of time, and I would often come home from school on a Friday to the scent of bread rising and baking in the house. While some people have a favorite song, I have a favorite smell. And for me, nothing compares to that of freshly baked bread. It takes me right back to my childhood, to that small room we called our kitchen. Humble, but capable.”

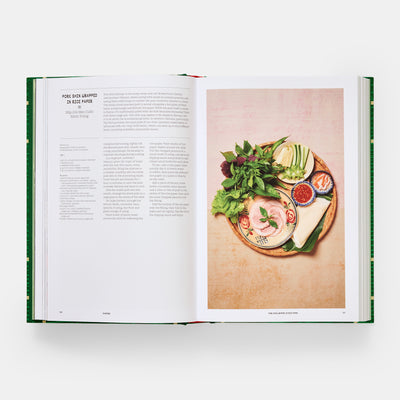

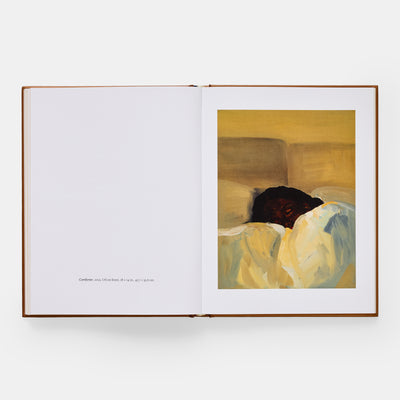

Beef Tasso. Photography: Nico Schinco

For Rawlston, cooking was one of the many joys of childhood. “It was our entertainment. We were not glued to a television. We were outside playing marbles, spinning tops, and hopscotch. And sometimes, we cooked. My friends and I would gather bhaji, a green-leafed plant known as callaloo in Jamaica, that was growing wild at the side of the road. We would light a fire in the yard and cook our own meals. We were not allowed to use the good pots, so we used what we had, which were often powdered milk cans. Looking back, I am not sure how safe it was, but I am still here.”

The Caribbean Cookbook is a testament to his journey, from being raised in a modest household in a small village to living in the United States, writing about the cuisine that shaped him. It’s a celebration of resilience, curiosity, and the beauty of telling one’s own story.

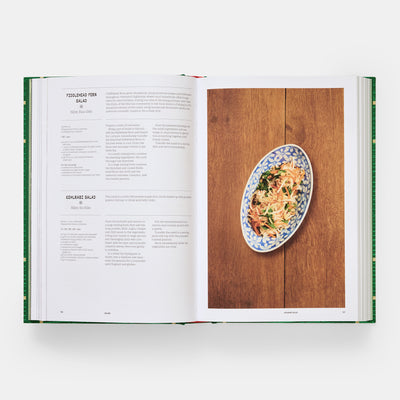

Soup Joumou. Photography: Nico Schinco

As he writes in the book: “This is a cuisine born out of scarcity. A cuisine made possible by people who had little and created plenty. I embraced the idea of writing this book. I owned it. I also knew I was not writing it just for myself. I was representing so many others, telling our story through the foods we made and the lives we lived. So I reached out to others. Chefs, cooks, and home cooks. From across the Caribbean and right here in Brooklyn, which holds the largest Caribbean community outside of the region. I met people in their homes, at restaurants, and at public hangouts. I listened. I learned.”

Take a closer look at The Caribbean Cookbook.