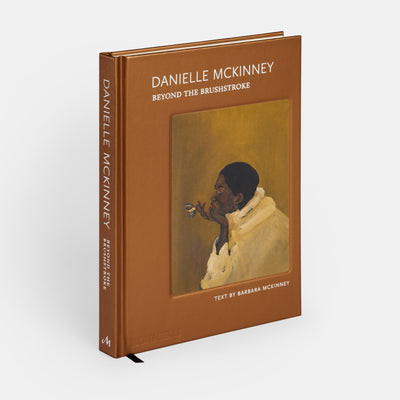

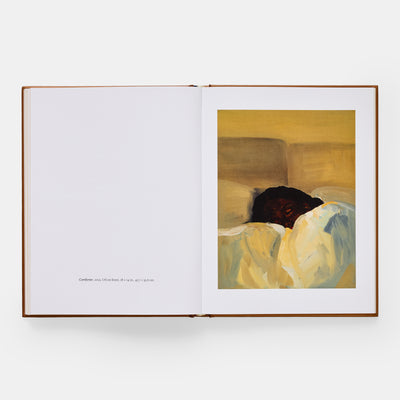

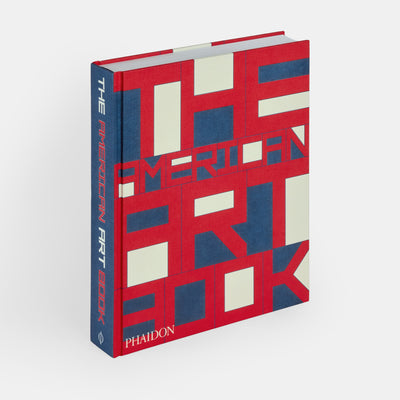

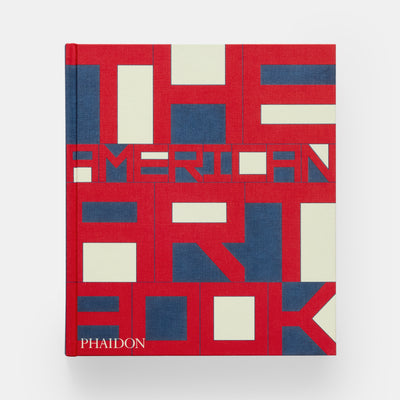

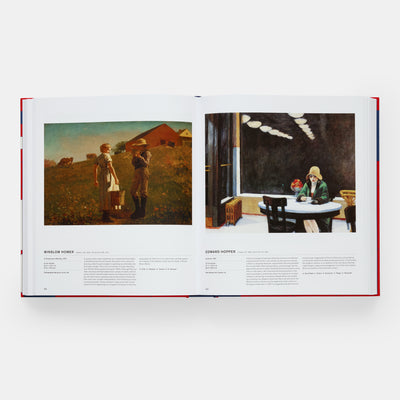

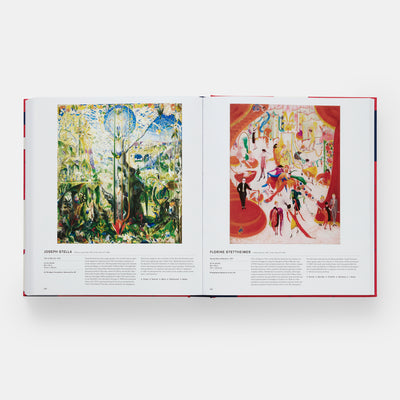

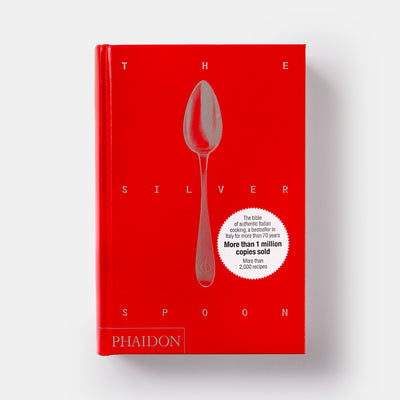

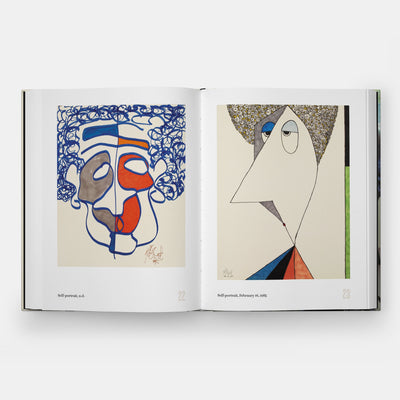

Are you lonesome tonight? The American Art Book would make for a great beside companion. This fully revised, beautifully printed, 512-page hardback offers readers a truly authoritative overview of America’s finest, most vital artists, each of whom has been carefully selected for inclusion in the book by an advisory team of leading curators, historians, and institutional directors.

There’s pleasure to be had in admiring the juxtapositions the A-Z arrangement of artists throws up, placing, say, Gordon Parks next to Maxfield Parrish, or Vito Acconci opposite Ansel Adams. Yet there’s also joy to be found in tracing the various forces that have shaped American image making, via the book’s pages.

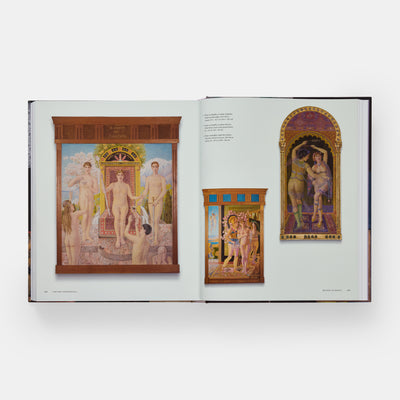

Consider sex, that universal drive that’s been suppressed and celebrated throughout American history. In early examples included within the book erotic desire is hidden under classical allusions, which in part enabled sexualized art to reach large audiences. Consider The Sleeping Faun from 1870, a marble sculpture of a slumbering, near-nude woodland spirit, and a mischievous satyr, by the pioneering, lesbian artist, Harriet Goodhue Hosmer.

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, The Sleeping Faun, modeled 1864, carved c. 1870. Cleveland Musuem of Art, Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, The Sleeping Faun, modeled 1864, carved c. 1870. Cleveland Musuem of Art, Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund

“Hosmer’s erotic yet whimsical take on an inebriated faun at rest was exhibited internationally at world’s fairs and exhibitions,” explains the book. “Hailed as the first U.S.-born woman to have a professional career as a sculptor, Hosmer received a progressive education in Massachusetts and Missouri before moving to Rome in 1852 with her then-lover, the noted performer Charlotte Cushman.

“She was internationally celebrated for her Neoclassical subjects, as well as innovations in turning limestone into marble and extending the modeling of plaster by adding wax to the surface,” the text goes on to explain. “Her business savviness, humor, technical skill, and unapologetic Queer visibility made Homer a confidant and mentor to many European and American artists and scholars.”

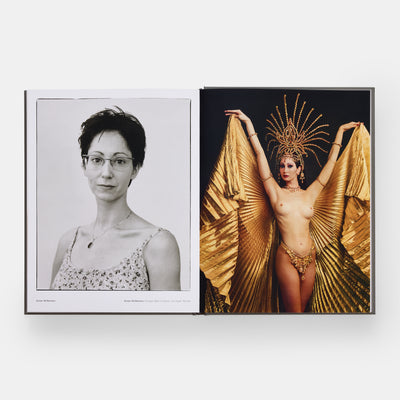

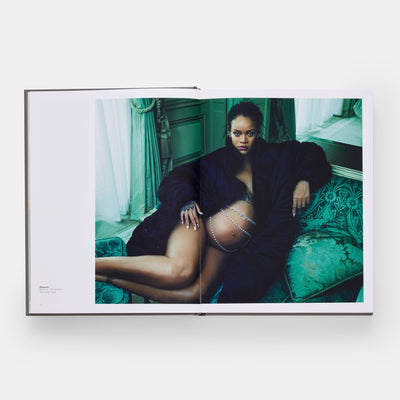

Much later depictions of sexual love can afford to be – or more accurately, demand to be – more open, even when, in some cases, the highbrow, Old World references remained. Take a look at photographer Catherine Opie’s 1993 portrait, Matt and Jo.

Catherine Opie, Matt and Jo, 1993. © Catherine Opie. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles; and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London. C-print, 20 × 16 in., 50.8 × 40.6 cm

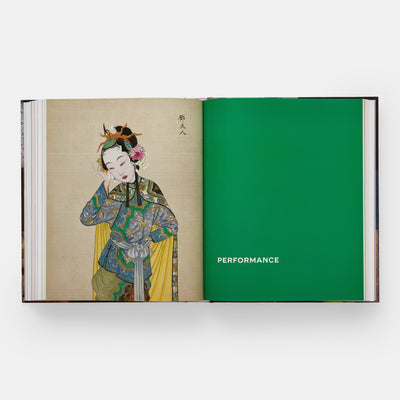

“Posed to mimic the stances of classical sculpture, Matt and Jo glow against a deep emerald backdrop. Part of a series of studio portraits Opie took of her Queer and transgender friends in the early 1990s, the image confers dignity, and perhaps more crucially, visibility on a community that had been variably erased, overlooked, or intentionally obscured throughout history,” notes our new book. “Purposefully evocative of an Old Master painting, the rich colors and formal compositions situate Opie’s close companions staunchly at the center of the Western art-historical canon.

“Since the early 1990s, Opie has established herself as one of contemporary America’s foremost documentarians. Seeking out communities of subculture and iconic landscapes alike, through her images of empty free- ways, teen footballers, Wall Street stockbrokers, and California surfers, Opie has fashioned an oblique portrait of the country itself, plumbing the prevailing mythologies of the American Dream, ultimately turning both its promise and its pitfalls into her most studied subject.”

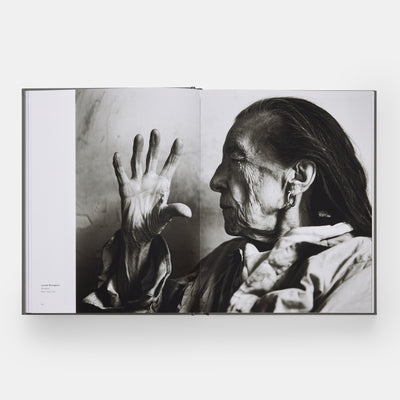

There are more openly sexual works in The American Art Book, as well as images that capture the intimate, personal, bodily obsessions that accompany erotic love. Consider Alfred Stieglitz’s 1920 photograph, Hands with Thimble, which falls into the latter category.

Alfred Stieglitz, Hands with Thimble, 1920. Courtesy Buhl Collection, New York,Gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in., 24.1 × 19.1 cm

Alfred Stieglitz, Hands with Thimble, 1920. Courtesy Buhl Collection, New York,Gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in., 24.1 × 19.1 cm

“Like the fingers of a pianist, these delicately arched digits seem poised to produce a magical chord, although the presence of the thimble suggests the more quotidian activity of mending,” notes the book, before revealing: “These are the hands of Stieglitz’s partner Georgia O’Keeffe, who would become one of the best-known American painters of the twentieth century.”

Stieglitz and O’Keeffe were deeply infatuated with one another at the point this image was taken, would marry four years later, and the photo was one of many in which the photographer expressed and captured his libidinous love for his fellow artist. “This picture is part of a remarkable serial portrait of O’Keeffe—comprising hundreds of images of her hands, face, and body—that Stieglitz worked on for more than two decades.”

Far from explicit, the image proves just how sensitively sex can be depicted in art. For more on these images and others, buy The American Art Book here.