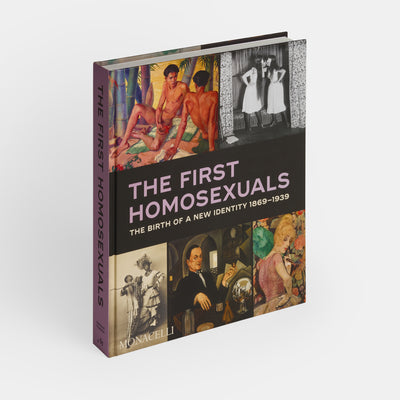

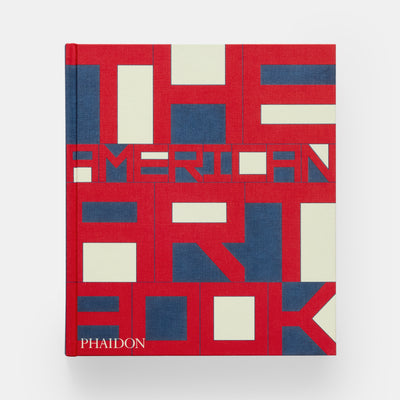

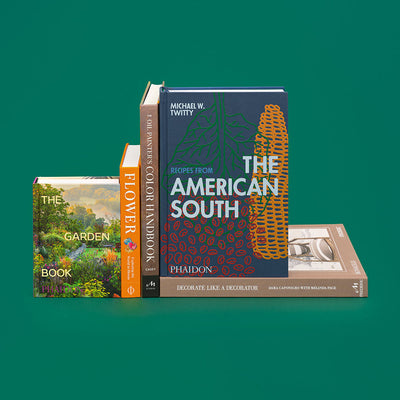

With its competing myths, ideals, cultures, traditions, ideologies and dreams, America is sometimes, as the great American poet Robert Frost put it in 1951, ‘hard to see’. Thankfully, our newly updated The American Art Book pulls the country’s greatest art and artists into sharp focus. This fully revised, beautifully printed, 512-page hardback offers readers a truly comprehensive overview of America's finest, most vital artists, each of whom has been carefully selected for inclusion by an advisory team of leading curators, historians, and institutional directors.

Part of the thrill of leafing through this book lies not only in the way its alphabetical arrangement throws, say, Christopher Wool next to Andrew Wyeth, or Weegee up beside Carrie Mae Weems, but also in the joy to be found in tracing the historical forces that shaped this remarkable country.

Consider the role of money and the American Dream in American art and society. The American Art Book covers more than three centuries, during which time the role and symbols of wealth and status have changed considerably. In the 1670 group portrait, David, Joana, and Abigail Mason, by the hard-to-identify society painter known to art historians as The Freake-Gibbs Painter (since he painted members of Boston’s elite, including the Freake and Gibbs families), conspicuous consumption is tempered by colonial mores.

"Facing his sisters in an authoritative stance, David Mason displays a gentleman’s gloves and walking stick while Joanna and Abigail hold symbolic feminine accessories in their hands,” explains the text in the book. “The children’s fine laces, linens, and accessories indicate their parents’ wealth and a pride in appearance that stretches the boundaries of Puritan modesty and strict sumptuary laws.”

The Freake-Gibbs Painter, David, Joanna, and Abigail Mason, 1670. Picture credit: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 × 42 1/2 in., 100.3 × 108 cm

The Freake-Gibbs Painter, David, Joanna, and Abigail Mason, 1670. Picture credit: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd. Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 × 42 1/2 in., 100.3 × 108 cm

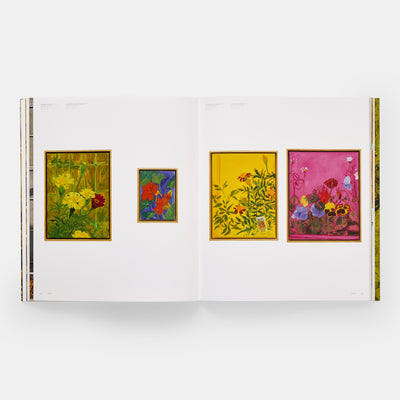

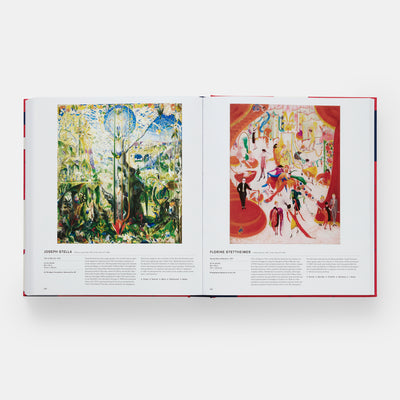

A little over 250 years later, and all such limits have been lifted. In Florine Stettheimer’s 1921 painting, Spring Sale at Bendel’s, the joys of money and spending during the Roaring 20s are picked out in primary colors.

(Main image picture credit: Florine Stettheimer, Spring Sale at Bendel’s, 1921. Picture credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art, given by Miss Ettie Stettheimer. Oil on canvas, 50 × 40 in., 127 × 101.6 cm.)

“Chic shoppers, their vanity affectionately but accurately caricatured, struggle to snag the bargains at Henri Bendel, one of Fifth Avenue’s fashionable emporiums,” explains our new book. “Red curtains charge the lively scene with a theatrical quality that emphasizes the dramatic behavior of the customers diving through piles of fashionable clothes.

“Stettheimer’s eccentric canvases, often high camp burlesques of the social and cultural life of New York’s upper echelons, are grounded in her extensive technical training and sophisticated knowledge of modern art,” the text goes on. “With an independent income and no pressure to exhibit or sell her work, she painted to please herself and her elite circle. Her work was hardly known until two years after her death, when the Museum of Modern Art’s memorial retrospective revealed Stettheimer’s singular chronicle of, as she put it, ‘America having its fling.’”

Pacita Abad, If My Friends Could See Me Now, 1991. Picture credit: Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Acrylic, painted canvas, and gold yarn on stitched and padded canvas, 94 × 68 in., 238 × 173 cm

Pacita Abad, If My Friends Could See Me Now, 1991. Picture credit: Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Acrylic, painted canvas, and gold yarn on stitched and padded canvas, 94 × 68 in., 238 × 173 cm

Sixty years on from that picture, that fling seems to have flopped a little, at least for some newly arrived Americans. In Pacita Abad’s 1991 multi media work, If My Friends Could See Me Now, the moneyed life portrayed in Stettheimer’s picture appears woefully out of reach.

“Scenes of life representing the American Dream - a house with a white picket fence, the glowing skyline of San Francisco, and a red car driving on the highway - surround a central portrait of Than Lo, a friend of the artist who immigrated to the United States from Vietnam in the 1970s,” reads the text in The American Art Book.

“Born into a family of politicians, Abad fled the Philippines in 1970 to escape political persecution after organizing a student demonstration,” the text goes on to explain. “She was renowned for her trapunto paintings: canvases that combined painting, quilting, and embroidery, at times also incorporating embellishments such as cowrie shells, buttons, and beads."

"Abad’s expansive perspective and personal history shaped her thematic choices, and she often explored subjects of social justice in her oeuvre. If My Friends Could See Me Now reflects on the idealized yearning for prosperity of immigrants in the United States.”

To better understand these works and many others, get a copy of The American Art Book here.