Jane Hall is that rare figure who moves fluently between practice, scholarship, and advocacy. She’s an architect, author, and curator whose work always widens the frame around what design can be, and, more importantly, who it should serve.

A founding member of Assemble, a London-based collective that won the 2015 Turner Prize for its community-rooted work in Liverpool, Hall helped demonstrate that architecture can be a collaborative social project as much as a formal pursuit.

Her own route to that eureka moment involved rigorous study and inquisitive fieldwork. She read architecture at King’s College, Cambridge, continued at the Royal College of Art in London, and completed a PhD in 2018 tracing the legacy of modernist architects across Britain and Brazil.

Before that, in 2013, she had become the inaugural recipient of the British Council’s Lina Bo Bardi Fellowship. Today, alongside curatorial and collective work, she holds academic roles in the UK and abroad.

Jane Hall - photo courtesy Jane Hall

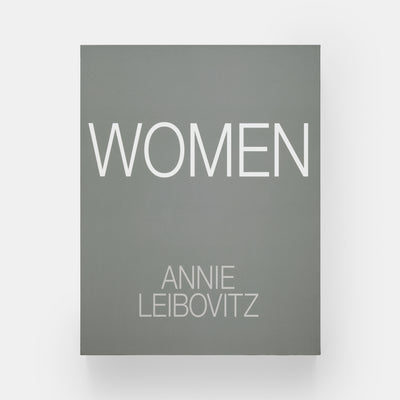

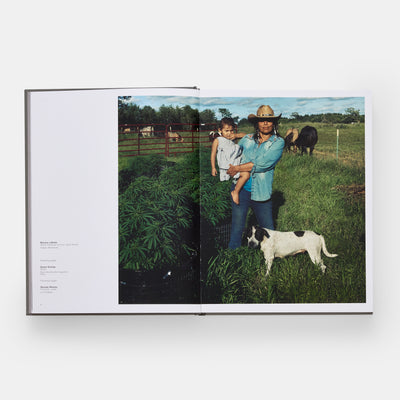

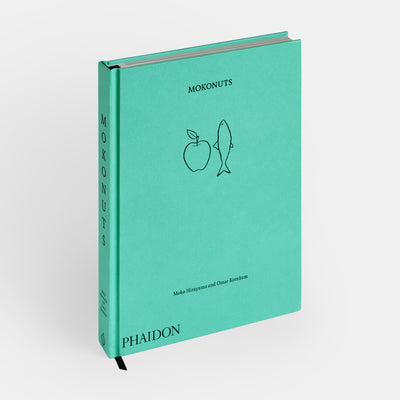

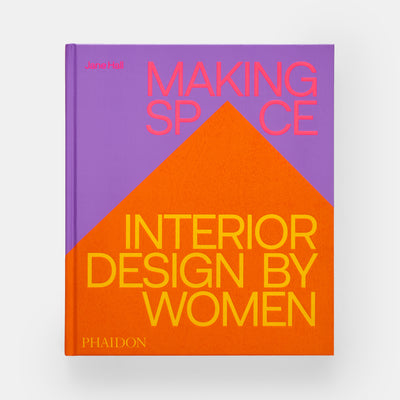

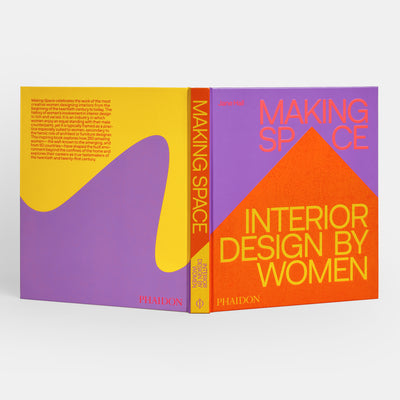

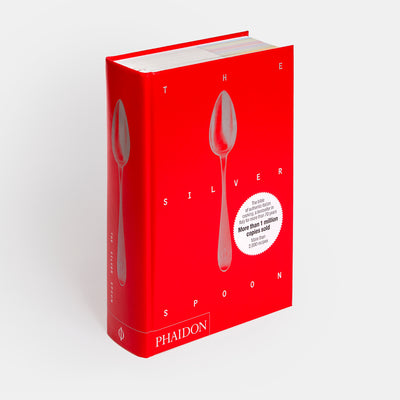

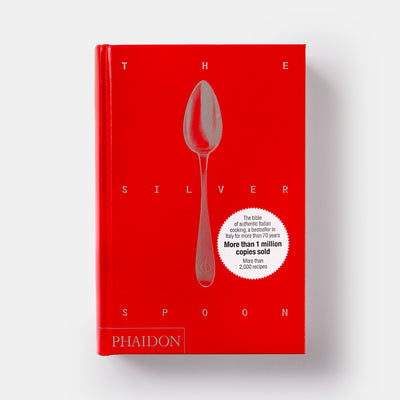

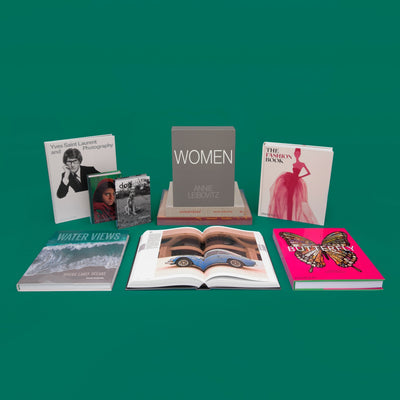

Her desire to rebalance the conversation around women in the creative arts runs through her acclaimed books for Phaidon. Her 2019 debut, Breaking Ground: Architecture by Women, is a panoramic, image-rich survey that restores hundreds of buildings to an architectural lineage too often edited by omission. It’s equal parts reference and revelation, making visible a century of practice that shaped cities but very rarely syllabi.

She widened her lens with 2021’s Woman Made: Great Women Designers, a global compendium of more than 200 practitioners whose work spans furniture, products, and graphics. Hall’s editorial touch, bringing together pioneers and contemporaries from across the world, repositions design history as a network rather than narrow canon.

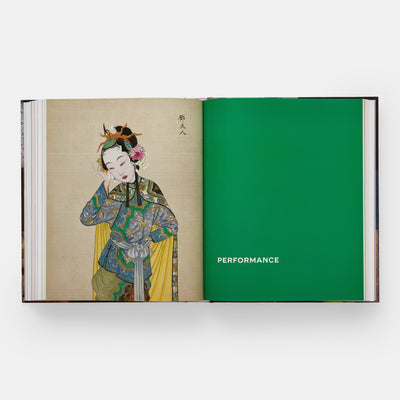

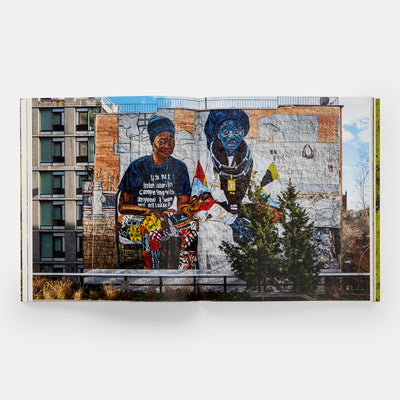

She focuses on interiors with her latest book, Making Space: Interior Design by Women. It’s a sweeping survey that charts the discipline’s evolution through the practices of 250 designers from the early twentieth century to now. It extends her ongoing aims to map influence where it has always existed but not always acknowledged. And, in common with her other books, she shows how expansive the world of design becomes when more of its authors are allowed a voice.

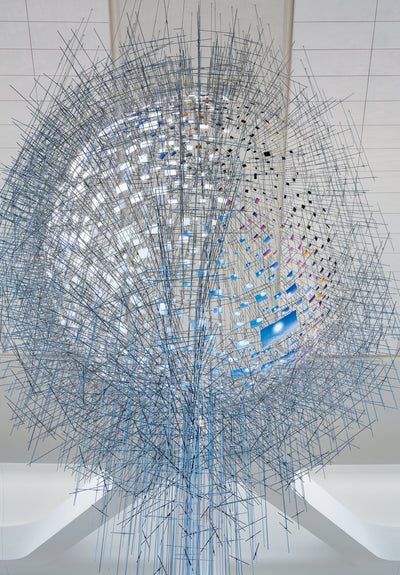

In the first of a two-part interview we asked her about the beginnings of Making Space: Interior Design by Women. (Main image Xiang Li, Loong Swim Club, Suzhou, China, 2019. Image credit: SFAP).

How would you describe the book? Like the other two books I've done with Phaidon, it's an amazing, hidden design history. This one is specifically for interiors, which seems to be understood as a female dominated profession, but in researching and finding out about these characters from the past, and also the present day, it felt like a really interesting history that isn't so well understood and one in which as designers, women had an early role. Mid 19th-century women were really involved in shaping space and impacting architectural space as well.

And like with Woman Made, you see this complete flattening of what design means. And how meaningful the domestic sphere really is. This book really focusses on domestic spaces. There's a dominance of living rooms. But the book positions that as being a really interesting site where ideas take shape and new aesthetics and new ways in which people's everyday lives can be changed began to hold much more meaning. Designers are talking about the relationship between space and grand scales, and you might think, but aren't we talking about your living room? So there are these big claims around how meaningful the domestic sphere actually is.

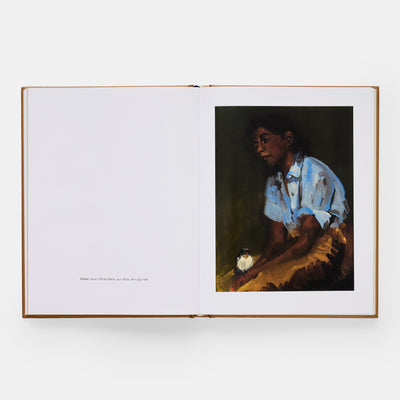

Rose Cumming, Cumming Residence, NY, USA, c.1929. Image credit: Courtesy of Sarah Cecil

What’s the thing that’s different about it? The book has the subtitle Interior Design by Women, because not everyone in the book would call themselves an interior designer. That's a very modern nomenclature, especially as interior design is very professionalised, but not a profession in the way that architecture and some other design disciplines are regulated.

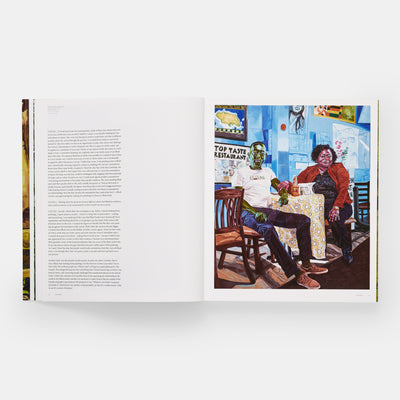

Interior design allows one to behave a bit more like an artist but it's very client led. This is what I found really interesting. Whenever I tried to really draw the people in the book out on their aesthetic, even when they had a strong style, everyone denied having one.

They would all say, ‘I respond to my client, every project is different.’ And so what interior designers do brilliantly is take their client with them and make it feel like it's the client's project while still retaining a strong stamp of authorship.

Whereas with Woman Made, often people are having to design products for mass production, and they have to fit what a massive fabricator or producer or a manufacturer is going to be able to supply and sell at a certain price point.

Interior design rather than architecture and furniture works a bit more like high fashion. Like the catwalk trickles down to the high street, that's also true, with interiors. What very good interior designers do is set a vision and create new ideas about shaping the world, and then people can achieve that in their own homes. There are much stronger trends in interiors than other of the design professions.

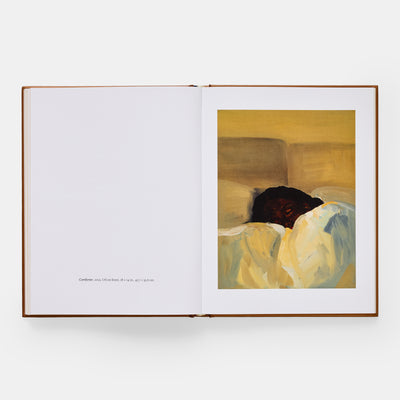

Dorothy Draper, Greenbrier Hotel, White Sulphur Springs, WV, USA, 1948. Image credit: Dorothy Draper & Co

Was there a moment when that more formalised approach replaced the earlier pioneers’ artistic expression? The Second World War really creates this bifurcation. Before then, most women who had a profession, were wives and daughters of wealthy people, and that's when maybe - because interior design is still a very moneyed world - people who were paying for it, often had the budget to realise something quite extraordinary. That's something that's carried on through the ages.

What I find amazing is that these women were able to express themselves in such an Avant Garde way. When I first saw Dorothy Draper's Greenbrier Hotel and it was, bright turquoise and black and white stripes and leopard prints, and I was like, what were you thinking? How did you get away with it? This is like nothing I've ever seen before. But in a way, it continued a decadence that was quite normal for that level of society.

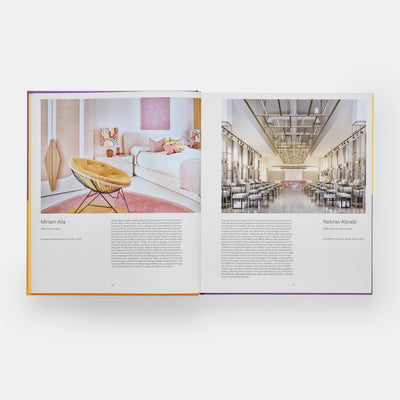

Nebras Aljoaib, FOURSPA IV, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. Image credit: Tamara Hamad

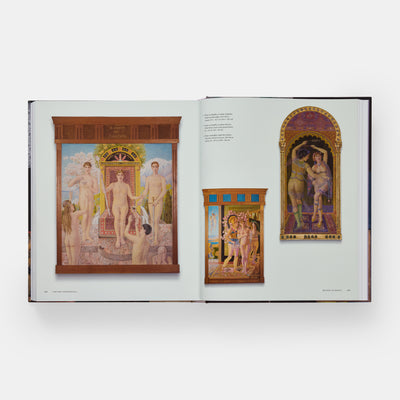

How much of it was a reaction to, or developed in tandem with, the art movements of the day? I was surprised to not find more interior designers from the Bauhaus or from Modernist schools. Interior design was anti-academic. It wasn't in an institution, it wasn't theorised. And so it was basically ignored. That’s how women got into it.

In fact, you've got some of the best, most extravagant interior designers throughout the ‘20s and '30s, when everyone else, we're told, is looking to modernism.

And sure, there are a lot of women who are doing that as well, like Adrienne Gorska, who did some really interesting stuff, but interior designers talk about this word ‘timelessness’ and it's got so much meaning. Everyone talks about it all the time.

There are two strands. There's the interior design that's always ignored, the popular currents. And then there are those people who've come from within those movements who've done things you could call interior design, like Nelly van Doesburg or Rietveld Truuss Schroder-Schrader (House) and Ray Eames. But for them, interiors were part of working and being an artist, whereas people who define themselves as decorators, they ignored movements and trends.

And they represented a different type of client. A lot of art movements, particularly in the 20th century, became much more concerned with everyday life, and so there was this extent of accessibility, efficiency, resourcefulness, refinement, mass production. Very wealthy individuals were not concerned with that at all and had different tropes that they wanted to see.

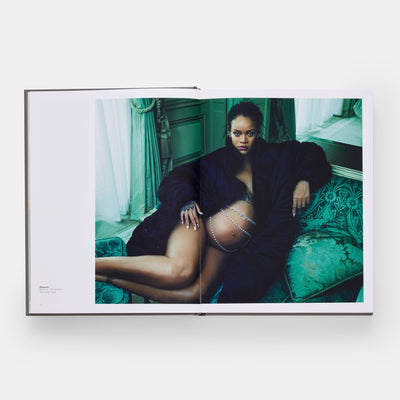

In a contemporary sense it's really interesting because we've got a lot of people in the book whose homes are featured, who are wealthy by other means, musicians such as Alicia Keys for example.

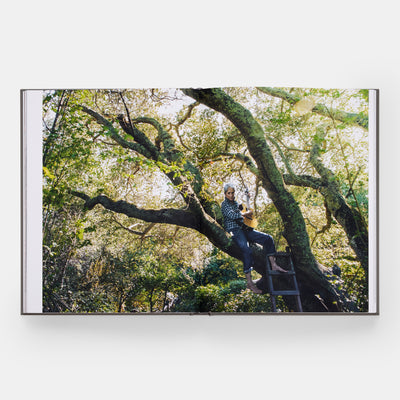

Ana Milena Hernández Palacios, Ana’s home and studio, near Valencia, Spain, 2023. Image credit: Luis Beltran

What were the other things you were surprised by along the way? I'm trained in architecture. In all the schools and professional environments I've been in, you're constantly told that interior design is a feminised world. In trying to make it as an architect you're told, or you get the impression, that being an interior designer is a cop out, or where women end up because it's not as tough.

It's not that I've never bought into these stereotypes, but in seeing the breadth of the work, and the way people work and talk about it, the artistry is definitely so much stronger. And so I see interior design closer to the work of painters and sculptors, rather than architects. Previously, I'd been trained to think of it as a sub version of architecture.

It could be because it doesn't have to deal with the elements that architecture has to deal with. It has to be robust enough, but it's not like furniture design where chairs have got to withstand use. It can be looked at and that has value.

Before starting this project, I probably wasn't quite sure where I would find value in the work. Having spoken to loads of people I’ve begun to understand the thought they put into it and how it's so much more open because you don't need a degree in it to practice. People have amazing backgrounds in fashion, in art, in all sorts of different disciplines. So that makes it really rich. And the idea of the repeat client is interesting too. You don't get many design professionals where there are so many really close and enduring relationships.

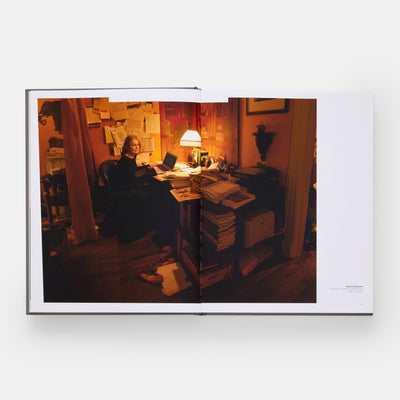

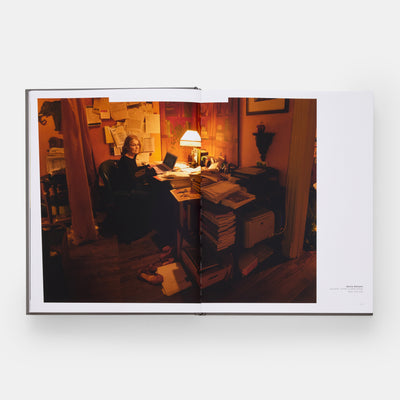

Nancy Lancaster, Nancy’s home, London, UK, 1957. Image credit: Simon Upton / Interior Archive

It was surprising to find designers like Eleanor Le Maire, who designed a Studebaker car. And there's one called Maria Bergson, who also did a car, who I included in the introduction. The thing with Lemaire was that she was thought to be able to appeal to women who were starting to have more control over the purse strings at home.

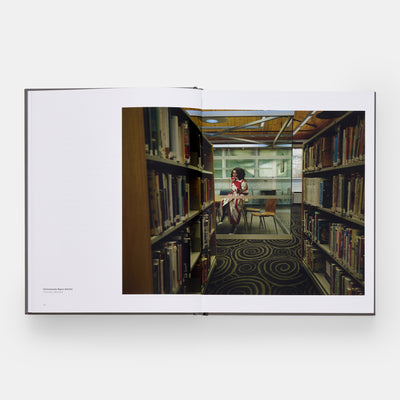

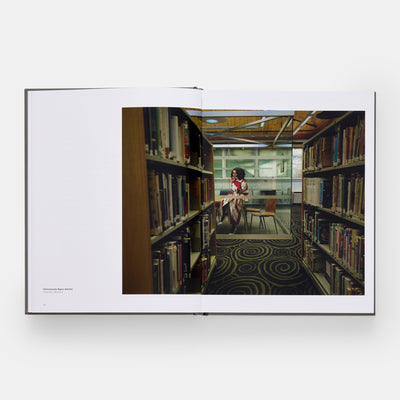

Florence Knoll, Cowles Publications Office, New York, NY, USA, 1962. Image credit: Courtesy of Knoll Archives

Which of the designers, in the post-war period, were the most influential? Florence Knoll is obviously one of the people that everyone has heard of, but I would also say people like Barbara D’Arcy, who did all the Bloomingdales. She was taking it to the mainstream. That was really about showing women, or people generally, how to build their interiors from the products that were on sale. But it was wild imaginative stuff as well, an immersive environment. She's one of those people who is very impactful but never really noted for it and no one at the time really knew that they were being impacted.

Then there are people like Eva Jurisna who basically bought high tech into retail stores. Steve Jobs was courting her to design the Apple Stores. She was the first person to do glass staircases. That use of glass and transparency that you see in Apple retail environments is possibly Eva's doing.

Then there were people like Marion Hall Best, from Australia, who did crazy pop 60s things with bright saturated colour blocking. We tend to forget that someone brought that into an interior environment for the first time.

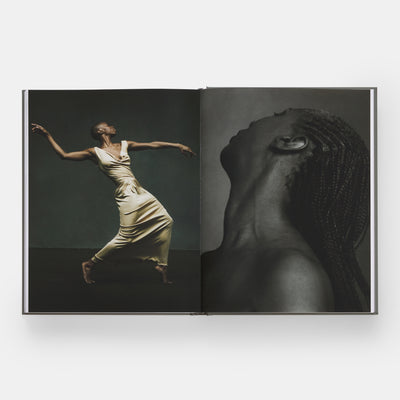

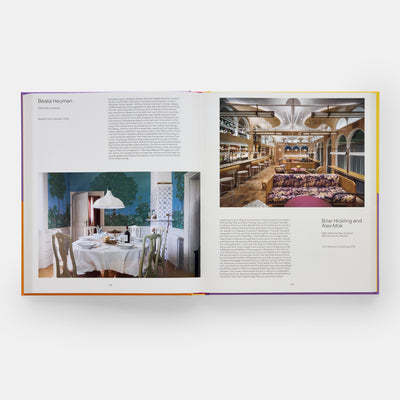

Sophie Ashby, Showroom at The Blewcoat School, London, UK, 2022. Image credit: The Blewcoat School by Studio Ashby, photographed by Kensington Leverne

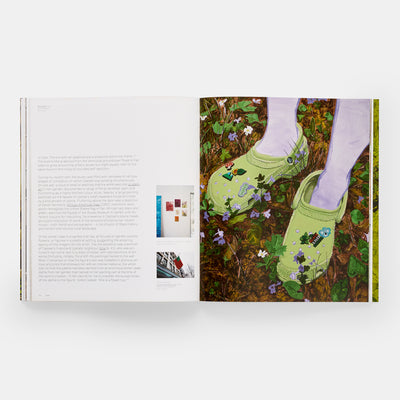

Do modern designers lack the resonance of those early pioneers, or do they have a different kind of resonance in an age when everything has to look good on Instagram? It’s more that the industry has expanded so much and people are very good at what they do. Interior design is incredibly hard to do well. Doing someone's living room in a two up, two down London townhouse is hard to do in an interesting way.

So you don't necessarily have the Dorothy Drapers anymore, but you do have people who are doing really amazing work like Alex Dorley who partners with Sophie Ashby to do United in Design. It's quieter, it's luxury, but it's accessible.

I think that's really hard to do. Then you have the people who are a bit more avant-garde like Pamela Shamshiri, who did stuff in New Orleans. Her stuff is much more saturated and richer and that's also very interesting.

And then you've got a lot of younger designers. There's this designer who's based in LA, who's Chinese called Jialun Xiong, who we featured a restaurant by in the book.

Among interior designers, there's this multidisciplinary ideal. A lot of designers today talk about wanting to have their own lines of furniture as well - people like Rose Uniacke - they have paint shops, furniture lines, fabric lines, so they're doing everything now.

A lot of young designers don't have the contacts that the designers in the past had, a lot of whom did their own houses and then their friends came round and commissioned them. Younger designers, who've maybe trained in design, who don't come from that background, are finding more opportunities in commercial spaces and environments. They want to be seen and so are willing to do something more interesting.

But then also, with Instagram and things, you've got to do more to stand out now. And so like Maye Ruiz, and Tekla Evelina Severin from Sweden, their work is colourful and obviously looks great on Instagram. I don't think that's why they do it, but their work lends itself to that medium.

I think that some designers are doing really good, strong work. It's actually much more complicated than it seems but, on Instagram it looks flattened, it looks generic; it doesn't look as exciting somehow. So it's been a double-edged sword for interiors.

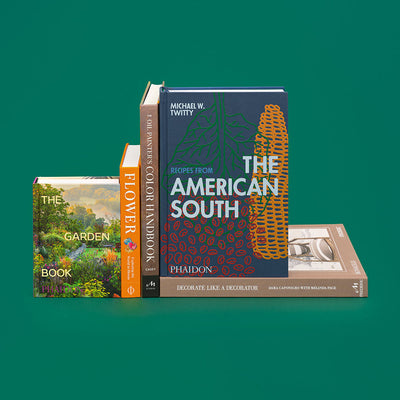

Take a closer look at Making Space: Interior Design by Women and look out for part two of our interview with Jane Hall next week.