William Monk’s paintings are alive with contrast - detail and void, figuration and abstraction, ritual and mystery. Guided by repetition and a poetic sense of gesture, his works invite viewers to dive into the in-between: between seeing and sensing, knowing and unknowing.

Monk’s practice explores the emotional terrain of lived experience, dreams, and memory. Known for working in series, his method is improvisational and iterative. He often begins with a single image - say, a cloud, vapor trail, or geometric form, and returns to it across numerous versions. “If I return to an image, it’s because that process of filtration hasn’t yet ended,” he says.

This repetition becomes contemplative, almost-but-not-quite ritualistic. “The idea of painting as mantra interests me," he says, "paintings as objects, figurations as images and models used as vibrations to reach somewhere else, beyond ourselves.”

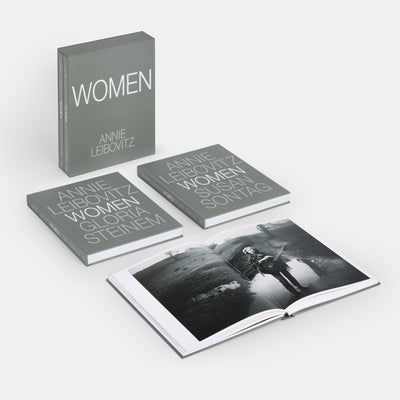

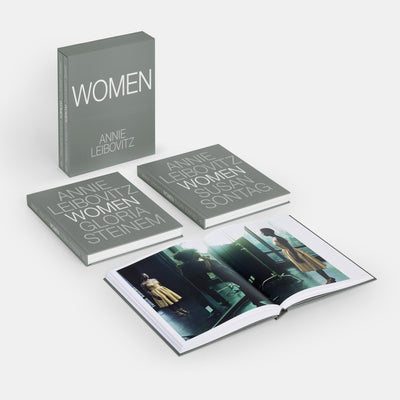

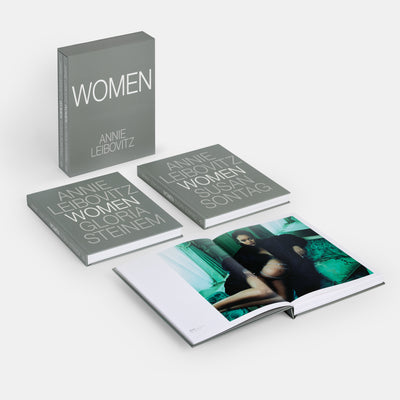

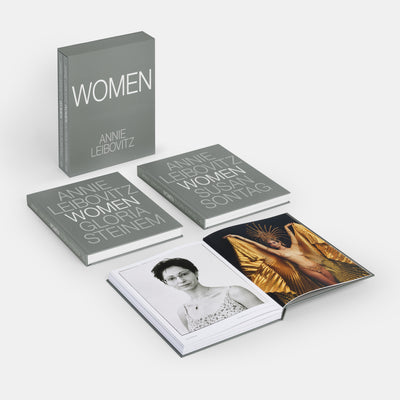

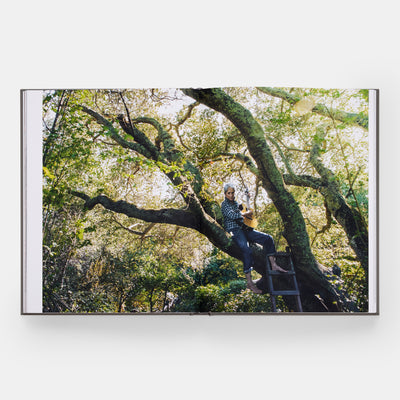

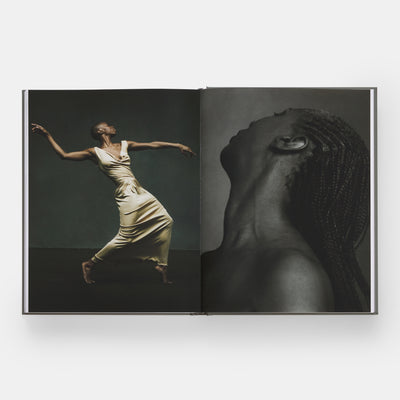

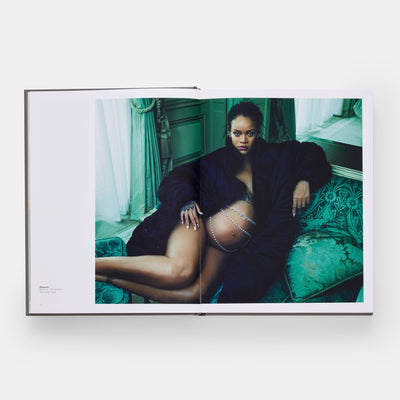

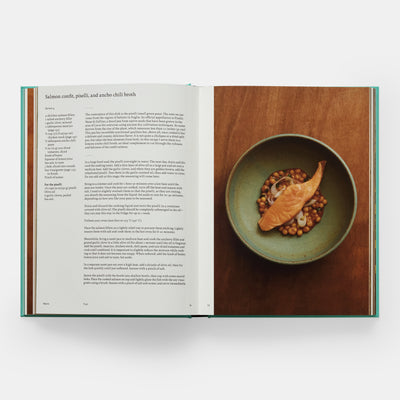

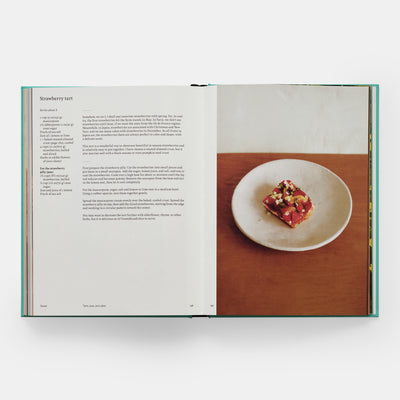

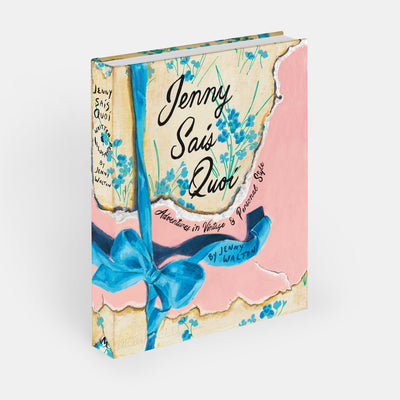

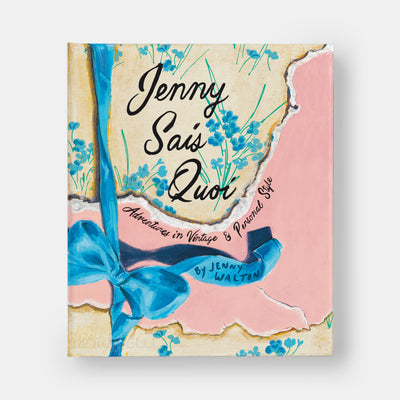

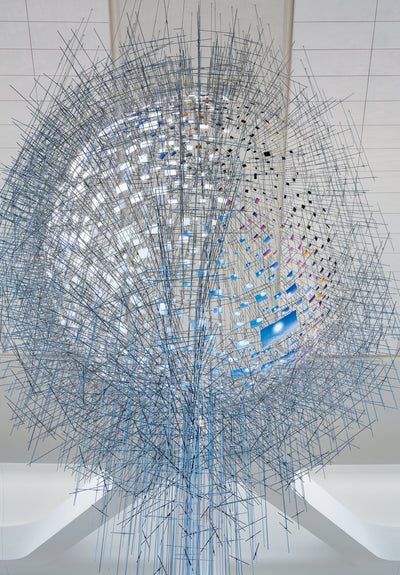

His new Phaidon limited edition lithograph, Mount Atom, 2025 presents a surreal vision - a levitating coral form suspended over a textured, pyramid-like mound, bathed in a soft, atmospheric glow.

Built up through seven layers of lithographic colour hand drawn on lithographic limestone combined with hand drawn photo plates, the work’s surface radiates with quiet intensity. The interplay of foreground, background, and textured repetition forms a visual mantra and exemplifies Monk’s ability to create compositions that feel both timeless and otherworldly.

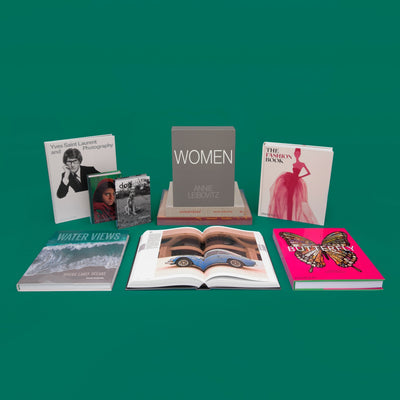

Limited to 50 signed and numbered prints, each edition is encased in a custom portfolio, including a copy of Phaidon’s new publication, William Monk, the first comprehensive monograph on his work. Mount Atom, 2025 offers collectors a rare opportunity to engage with the artist’s themes on a more intimate scale. Taken together, the Phaidon catalogue and print provide an unprecedented look at Monk’s oeuvre.

William Monk - Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Garrett Carroll

William Monk - Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Garrett Carroll

Monk has been represented by Pace Gallery since 2019, and his dynamic works have featured prominently in Pace exhibitions in London, New York, Los Angeles and Honk Kong. His psychological paintings are held in prestigious public and private collections worldwide, and can be found in the collections of the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (NL); Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami; Fries Museum, Leeuwarden (NL); ING, Amsterdam (NL); The Long Museum, Shanghai; Sifang Museum, Nanjing; Blenheim Art Foundation, UK; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles, among others. Monk was the recipient of the Jerwood Contemporary Painters Prize (2009) and Royal Award for Painting (2005). On the eve of the release of Mount Atom, 2025, we asked him a few questions about the print and his wider practice.

How did this particular edition come about, it’s your first, isn’t it? Well, I've never made a professional print before. About 10 years ago, I wanted to try my hand at this, and I chose woodcut because I thought that would be the easiest way in, without any understanding or knowledge. So, I watched a YouTube video or two and bought myself some tools. And I made two wood cuts, but they took so long to make, and I never had the time to really get into it, even though I've always wanted to do it. I didn't have the facilities. For this edition I've been working with Anna, a professional printer who's been great and who’s made the whole process very easy.

Can you tell us a little more about the image? I chose a previous painting to work from, one with essentially three elements: cloud, sky, and land. But it turns out that it was quite complicated to turn into a lithograph and keep it as painterly as the painting.

When did you make the original artwork? During the lockdown. I was making a show called Mount Atom, and this lithograph is called Mount Atom 2025. It was a two-part show. I was also doing one in another show in another part of the world that was called Point Datum. The two shows were related. They all had that ambiguity of figuration and this was one of the images exhibited.

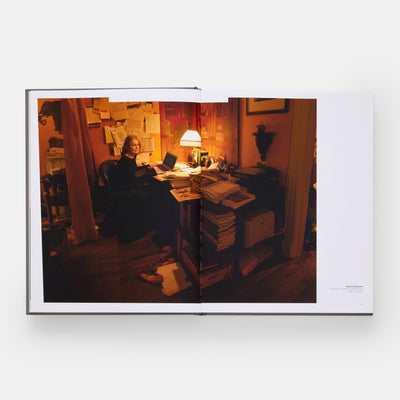

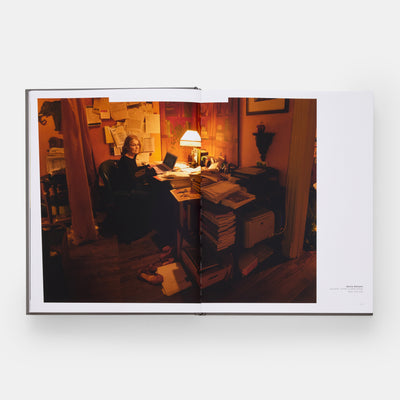

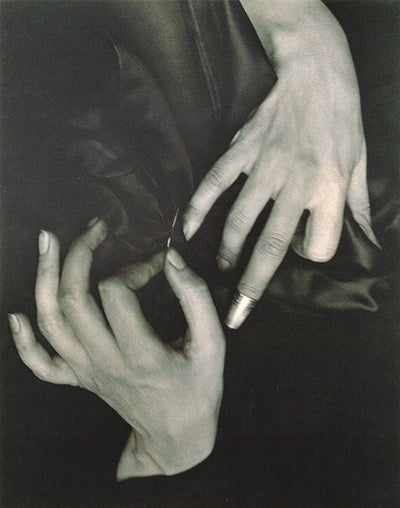

William Monk and Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Nir Arieli

William Monk and Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Nir Arieli

What role does memory or the subconscious play in the work? It's really difficult to figure out where it all begins, because paintings begat paintings, every painting breeds another one. And so, it's very difficult to know who the ultimate parent is.

You’ve spoken about painting as a form of trance or ritual, can you walk us through what a painting session feels like for you? There are times when I'm working at the front of my brain, and I'm aware and I'm conscious, we might even describe that as figurative. And then there are times where I'm switched off in that state and I'm working on kind of a ‘Neo dodging bullets time’, where everything slows down and you're just in the groove.

When all of this stuff is going on in your head and you look at what's appearing on the canvas, how do you perceive the connection? I don't know. When I see the paintings in the studio, I feel close to them and that I made them. And it's not really until they leave the studio and I see them in a clean gallery setting, for example, where I am surprised at what I've done. Particularly with the moments that we've just described, with the ones where you weren't really aware of you making them. You really are surprised to see it and you think how did I do that? Not in a showy off way, but just how do they do that on any level? Have there been any paintings where you've had a particularly intense variation of that feeling? I've got children now, so the most creative times tend to have happened at night when I was younger. I don't have so many opportunities to paint at night now. So, one has to force oneself. I have to do various things in the studio just to get in the zone. But there's one painting I made years and years ago that I painted in 17 hours straight, literally from start to finish. It doesn't look like it's a painting that was made in one sitting. It looks as resolved and as full as any painting I've made, but I did it in one go. I just wasn't willing to stop.

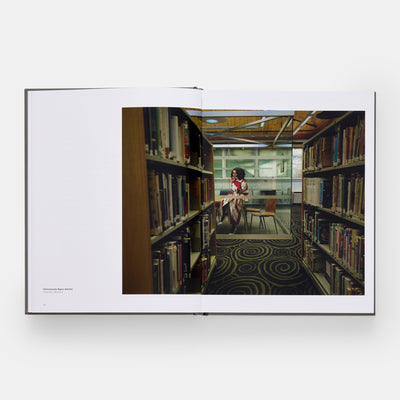

William Monk - Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Garrett Carroll

William Monk - Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Garrett Carroll

How aware are you that you see things differently to other people? I don't know that I'm any different to anyone else. I think I'm probably more visually sensitive than most people. I'm also quite agoraphobic and my tolerance for visual noise is low. How things look pleases me, or bothers me, in a more exaggerated way than perhaps it does other people. Do you work on multiple paintings at once and, if so, how do they relate to each other across the studio space? I do; I work on as many paintings as I have space for in the studio. At the moment there are too many. I have about 30 plus canvases on the go at the moment, which is too much, and I've had to put some away and try and ignore them. I'm probably working on about half a dozen paintings at a time that I'm thinking about.

When you're making a painting, all the elements of the painting should relate to each other in some way and have some dialogue with each other. I feel that is like a fractal and so the paintings should have a dialogue with each other. The shows too should have a dialogue - not that they should all be the same – but there should be some connection and through line. So yeah, when I've got an exhibition, I make the paintings for the exhibition and I'm working on the whole thing at once and orchestrating it all together.

If you're a gallerist that enjoys getting involved in the hang, my hangs are very boring because by the time I've got the paintings at the gallery I know where they're going to go. I've designed the exhibition in advance.

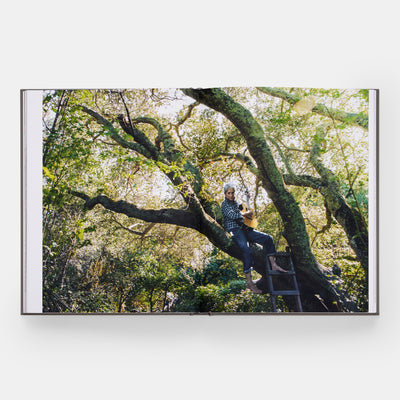

William Monk - Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Garrett Carroll

William Monk - Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Garrett Carroll

How important is the sequencing, scale, and rhythm when you come to exhibit the work? I'm like a frustrated filmmaker. I wanted to be a filmmaker once upon a time. And did a short film school thing, and realised I have the personality to be a painter more than a filmmaker. Filmmakers have to have greater social skills than a painter needs to have. You have to be a hustler to be a filmmaker, because you need other people and nobody's going to do anything for you if you don't have the art of convincing people. Being a painter, you don't have to have any of that attitude. You go where the weather suits your clothes and so I became a painter.

So, these shows are my little movies and the scale, the size, placement of the paintings, it's all a montage. I think these things are all universal things for painters. I just think that some things I'm more aware of than other things. I think a lot of painters take a lot of things for granted and they work within the form, without understanding that it is a form, and that it can be played with and manipulated.

I noticed with my big paintings; I tend to hang them very low to the ground. I invariably have a conversation with the gallerist about how high the painting should be, because their instinct is always to hang them at a certain level, but paintings look smaller when you hang them higher up. And so, I hang certain paintings very low to the ground. When they have a relationship with the floor where our feet are, it brings them closer to us.

William Monk - Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Garrett Carroll

William Monk - Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Garrett Carroll

Are there any other elements you use to bring the painting ‘closer’ to the viewer? I've got some handprints in some of my paintings. I didn't really do that consciously. It was more back of the brain stuff, but it keys the painting into a human scale. With a lot of the paintings, the scale of the paintings, or the scale of the image that's in the painting is really only whatever the viewer thinks it is. And one makes assumptions about what one's looking at with my work. But most of it is down to you.

Some of these paintings of these mounds of Planet Earth strata - whatever it is - at the bottom. I've literally given away nothing to indicate whether this is a mountain or whether this is a pile of dirt. It could be an ant hill. It could also be a tabletop mountain. The figuration happens in your mind's eye. And so, I hope that the scale is always human, relative to the person looking at the paintings, and makes the person become almost as aware of themselves as they are of the painting, and certainly as aware of the space, so they're not just thinking about an image.

Take a closer look at Mount Atom, 2025 here.

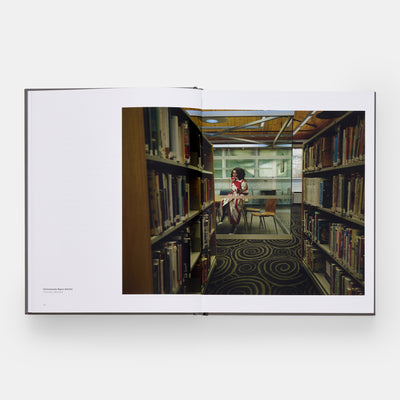

William Monk and Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Nir Arieli

William Monk and Mount Atom, 2025 - photographed by Nir Arieli