Contrast and continuity in Chinese art

By pairing works from different ages, the Chinese Art Book explores both shifts and stability within the nation

The Chinese Art book is an absolutely imperative purchase for anyone curious about the art history of the world's oldest continuous civilisation. With China increasingly coming into its own on the world stage, this volume is all the more important. It sheds a great deal of light on China's ever shifting social and political history, its dynasties and dictatorships, and its struggle to reconcile tradition and modernity.

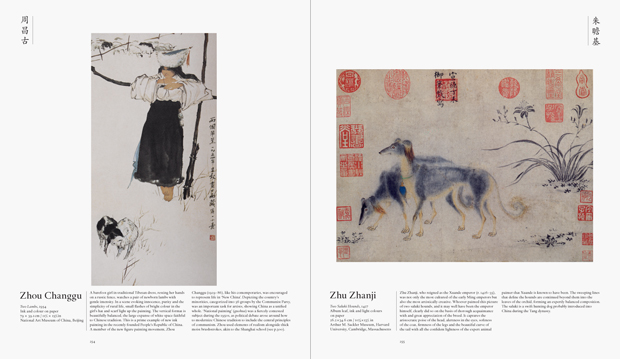

This is enhanced by the way in which the editors have laid the book out. Rather than proceed chronologically, they pair off works from differing ages, often highlighting their ironic similarities, stressing both continuity and contrast. So it is with Zhou Changgu's Two Lambs (1954) and Zhu Zhanji's Two Saluki Hounds (1427).

Two Lambs is a studied evocation of the purity and innocent simplicity of rural life, a tableau of rusticity, featuring a barefoot Tibetan girl fondly gazing on a pair of frolicking newborn lambs. Despite its tranquility, its genre, that of “National Painting” was the subject of fierce political debate in the newly founded People's Republic about how to incorporate the tenets of communism into Chinese tradition. Zhou was fulfilling a task set out by the ruling Party to depict the country's carefully categorised minorities, arranged into a unified whole.

Two Saluki Hounds is not merely art by order from on high – it is very probably painted by the Emperor himself. (Zhu Zhanji reigned as Xuande Emperor between 1426 and 1435). It's certainly expertly and sensitively composed, in particular the contrast between the softness of the hounds' coats and the sharp alertness of their eyes. Although they are centuries apart, these two works hardly feel poles apart, even if Zhou was working under more considerable constraint than Zhu, who presumably answered to nobody.

Keen to find out more? Then allow editor, Diane Fonteberry, to introduce the book here; you can browse through a gallery of images here; or read about some highlights here, and when you've done that, why not buy the book from the people who made it, here.