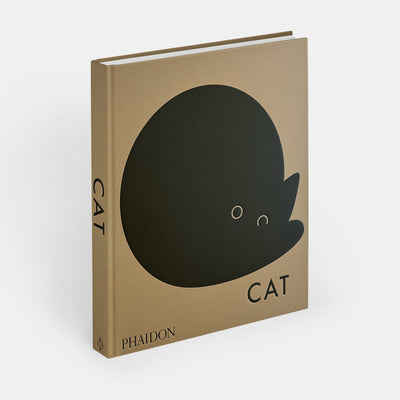

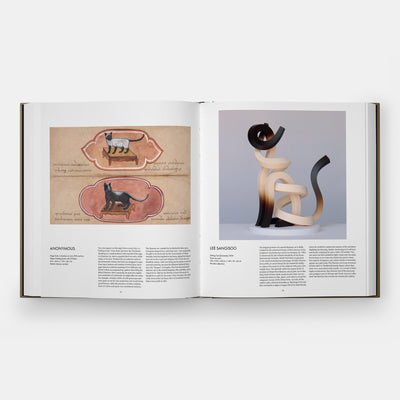

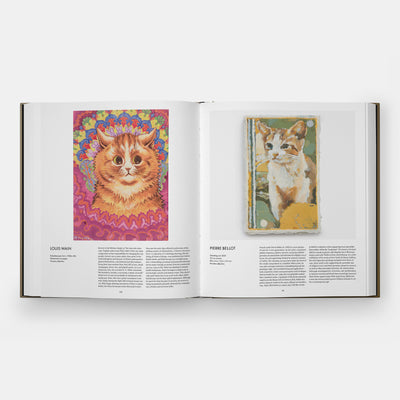

Packed with images of magnificent moggies throughout the ages, our CAT book has become one of the fastest selling of our new season books.

The book celebrates humanity’s enduring connection to our feline friends, taking readers on a journey to discover the endless ways the house cat has inspired artists and image-makers across continents and cultures.

As one of our oldest animal companions, cats have been adored and represented by humans for millennia. In the US alone, nearly 50 million households today boast cats as pets, and these much loved moggies have a long visual history that stretches well beyond their favorite corner of the sofa or inside an empty Amazon box, all the way from ancient Egypt, in fact, up to today in art and popular culture.

For our new book, we narrowed a literally limitless choice down to 211 spectacular images, selected in collaboration with an international panel of experts that includes curators, cat behaviorists, artists, and even the founding director of New York’s Cat Museum.

The works in Cat are each accompanied by an accessible text and illustrate a diverse, global selection of felines that span multiple mediums—from Japanese maneki-neko lucky cats to Disney’s The Aristocats, ancient mosaics to contemporary couture, and artists’ pets to Chia Pets. Here are five more of our (very) furry friends featured in CAT.

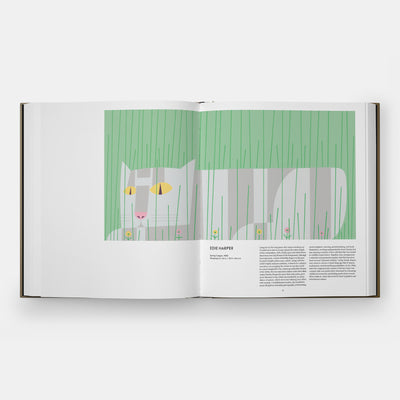

EDIE HARPER - Spring Creeper, 1980

Edie Harper, Spring Creeper, 1980. Picture credit: © 1980 Edie Harper Serigraph

Lying low in the long grass, this curious-looking cat is scaled up in size to occupy almost the entire length of the composition, with a bulky gray-and-white frame that towers over tiny flowers in the foreground. Although inconspicuous, a sense of timidity lingers in this gentle giant’s bright yellow eyes, which, along with the artist’s highly stylized aesthetic, connects to a playful narrative, encouraging the viewer to see the world in a more imaginative way. American artist Edie Harper (1922–2010), who was married to fellow artist and collaborator Charley Harper for more than sixty years, grew up in Missouri in the 1940s surrounded by an abundance of nature, which led to her lifelong love affair with animals. A multitalented creative, she excelled in many disciplines, including photography, printmaking, wood sculpture, weaving, jewelrymaking, and book illustration, working independently from Charley but also sharing a creative vision with him that was rooted in wildlife conservation. Together, they championed a reductive and geometric graphic style that has since been termed “minimal realism,” using simple shapes and colors to convey a visual language full of charm, exuberance, and storytelling possibilities. In the 1980s, when the original acrylic version of Spring Creeper was created, Edie was particularly interested in unlocking childhood memories, gravitating particularly toward feline subjects, which she loved for their inquisitive and mischievous nature.

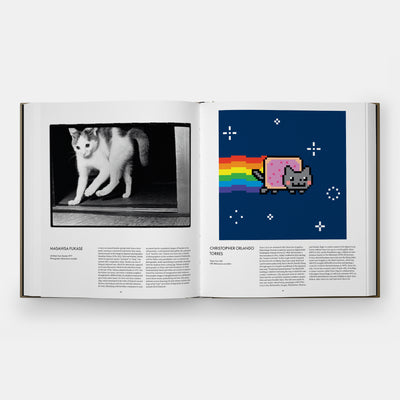

MASAHISA FUKASE - Untitled, from Sasuke, 1977

Masahisa Fukase, Untitled, from Sasuke, 1977. Picture credit: © Masahisa Fukase Archives, Courtesy Atelier EXB. Photograph.

A wary cat named Sasuke springs back from a doorjamb, wearing a concerned expression that seems almost human in this image by Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase (1934–2012). Alert and nimble, Sasuke, which in Japanese means “assistant” or “help,” was named after a legendary ninja. Sasuke was one of Fukase’s beloved cats, which he obsessively captured on 35 mm film and to which he devoted three books in the late 1970s. Fukase adopted Sasuke in 1977, but the kitten ran away, and when a helpful neighbor brought back a different kitty, he adopted it instead and gave it the same name. So close was their relationship, which developed in the wake of Fukase’s second divorce, that Fukase took his cat with him wherever he went, identifying with his feline companion to such an extent that he considered images of Sasuke to be self-portraits. A self-declared ailurophile who claimed to be “mad for cats,” Fukase was born into a family of photographers on the northern island of Hokkaido, and his father and grandfather ran a commercial photographic studio specializing in portraits. Familiar with the medium from a young age, Fukase studied photography in Tokyo and went freelance in 1968. Predominantly black-and-white, his oeuvre is characterized by extremes of transgression and violence, from graphic images of slaughterhouses to a celebrated series about ravens symbolizing lost love. His quiet, intimate scenes featuring his pets always eschew the trope of the “cute” cat in favor of depictions of soulful animals full of character.

ELIZABETH RADCLIFFE - Algie, 2024

Elizabeth Radcliffe, Algie, 2024. Picture credit: Courtesy Elizabeth Radcliffe and Margot Samel, NYC, Photo: Matthew Sherman. Wool and cotton warp. Private collection

At first, this might seem to be a photograph of a cat lolling about on an Oriental rug. Look closer and the composition reveals itself: the work is actually, cheekily, a woven textile. Scottish artist Elizabeth Radcliffe (b. 1949) is intent on taking the ancient art form of tapestry into the modern day, particularly in her deployment of three-dimensional imagery into flat-woven panels. A trained artist who specialized in weaving as an undergraduate at Edinburgh College of Art, she spent most of her career as a high school art teacher but returned to her own practice full-time after retirement. Radcliffe’s intricate, large-scale weavings often depict the human figure at life-size or details of clothing in shaped silhouette, so that they appear as if they have been cut out from the literal and metaphoric fabric of their surroundings. A man named Marc in plaid pants sitting in an armchair or just the shoulder of Marta wearing a tomato-red sporty jacket are recent examples. Another one of Radcliffe’s favored subjects is animals, because she is especially interested in their interior lives, what lies behind their eyes. In this work, Algie the cat stares intently at the viewer, almost accusingly, as if it has just been awakened from a peaceful slumber. Locked into the animal’s gaze, it is impossible not to feel a part of the scene. An original voice, Radcliffe pushes the boundaries of what woven art can be and will become.

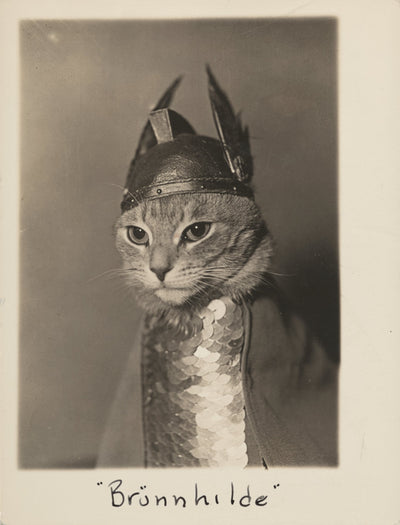

ANONYMOUS Cat and Kittens, c. 1872/83

A calico mother cat stares sternly out of this feline family portrait as her two rambunctious kittens toy with a ball of yarn in a classic scene of domesticity. Although not much is known about the anonymous American painter who created this work, Cat and Kittens is a jewel of American naive art and one of the most popular cat-centric canvases in the National Gallery’s collection. Also known as folk, primitive, or provincial art, naive art is defined by the flat and two-dimensional yet brightly colorful and highly individual painting style employed by self-taught artists in the United States from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. The planar forms and vibrant color palette here are markers of naive art, even if Cat and Kittens is a later example of the American school. Many folk artists were itinerant, traveling around the countryside to paint on commission, usually creating portraits of well-to-do farmers or townspeople and their families. Naive painters were less likely to make still lifes, landscapes, or other kinds of genre scenes, so this feline portrait is also unique for its subject matter. The cats here are rendered almost realistically, with the tabby kitten on the left appearing more true-to-life than its awkwardly standing sibling tangled up in yarn. The work also boasts intricate details, from the uniform pattern of the blue wallpaper to the delicate rendering of embroidery on the curtain. For a final elevated touch, the anonymous artist emphasized the powerful mother cat’s gaze by encircling her pupils in shimmering gold leaf.

JODIE NISS - Untitled (#2), 2022

Jodie Niss, Untitled (#2), 2022. Picture credit: Jodie Niss Oil on wood panel. Private collection

It is common for people to ascribe human behaviors to animals, particularly their pets. In doing so, they strengthen the bonds they share by identifying commonalities. It is also a means of transference, a way to attribute feelings to an avatar outside of themselves. This anthropomorphized cat strikes a very human pose in American artist Jodie Niss’s painting Untitled (#2). The fluffy feline slumps against a mirrored wall, its legs hilariously splayed. It could be sleeping soundly, or one can even imagine it meowing loudly and despondently. What, the viewer must wonder, has caused this sudden collapse into slumber or hysteria? Niss, a New York–based painter and art teacher, typically works in oil paints and watercolors. Although animals are a frequent motif in her work, her cat paintings began somewhat by accident. She started by painting portraits of cat owners but over time realized that she was more drawn to the expressive abilities of the felines themselves, which possessed personalities that telegraphed both human emotion and a quixotic kind of magnetism. By using animals as proxies for people, she believes that viewers can more readily relate to the imagery and see themselves in it. Indeed, one can envisage being so bone-tired or upset as to collapse on the spot, mouth agape like the fat cat in this painting, either dreaming or howling, depending on the viewer’s mood.

SALLY J. HAN - Nap, 2022

Sally J. Han, Nap, 2022. Picture credit: © Sally J. Han, Photo: Jason Mandella. Acrylic paint on paper mounted on wood panel. Private collection

This painting captures an enviable moment of peace and quietude shared between pet and owner, evoking emotions related to comfort, security, loyalty, and love. A work by Korean and Chinese American artist Jingmei “Sally” Han (b. 1993), the painterly style bursts with color and texture. The atmosphere of cozy cocooning is enhanced by the composition’s unusual bird’s-eye view, with the orange cat staring up as if a sentry, on duty while its companion snoozes. Han is known for her uncannily realistic depictions of everyday life and interiors that explore the human condition and universal emotions. Cats and birds are often present, as are figures in Korean and Western dress, usually paused in the middle of some action, such as playing a game of mahjong or allowing a cup of coffee to cool. Through nuanced narratives, subtle symbolism, and a vibrant color palette, Han conveys her own experiences as well as explodes them out, attempting to create some sense of universality through her intimate scenes. Poignant as they are, her paintings are intended as platforms for individual thought, as the artist explains: “Personally, I want my paintings to speak for themselves, so I don’t usually explain my work in detail. However, no matter what I paint, I aim to create art that, like the simple actions of a cat, can easily captivate people and leave a lasting memory

Take a closer look at CAT.