Get lost and found with the USA's leading map man

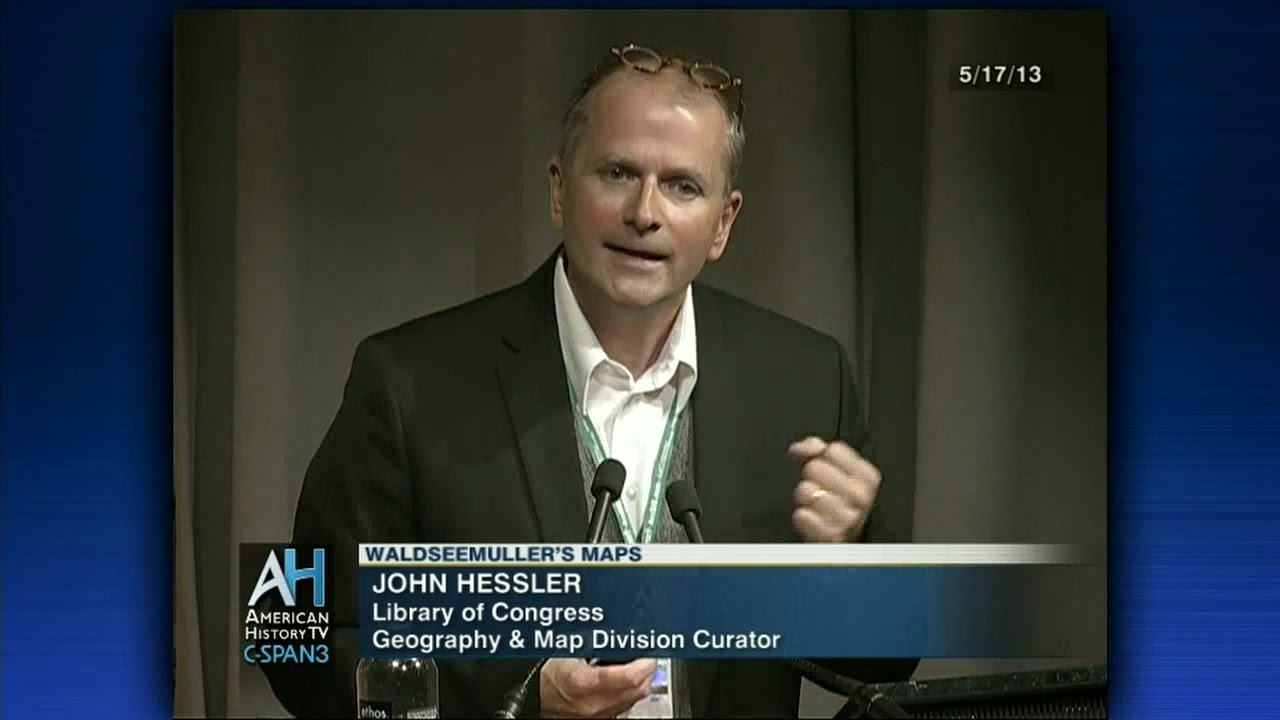

John Hessler, one of the US government’s foremost cartographic experts, on brain diagrams, big data and GPS

John Hessler doesn’t mind getting a little bit lost. “Except for when I’m in my car, I tend not to use GPS,” says Hessler who, aside from being Specialist in Modern Cartography and Geographic Information Sciences at the Geography and Map Division of the US Library of Congress, and the editor of our new book Map: Exploring The World, is also keen hiker, mountaineer and mountain biker. “I prefer the paper maps, not from any ideological point of view, but more because I like to take in my surroundings, and perhaps not know where I am exactly at every given point.”

Hessler has no shortage of maps to choose from. The Library of Congress owns the largest and most comprehensive cartographic collection in the world with over 5.5 million maps, 80,000 atlases, 6,000 reference works and 3,000 raised relief models, as well as sundry cartographic materials in a myriad of formats.

John and his colleagues not only oversee this trove, but also supply bespoke maps to the United States Congress to inform policy making. “They ask for maps relating to things like health care, or public transport,” John explains. “I am not at liberty to divulge any recent requests, but if you see a map on [US government TV channel] C-SPAN, it could well have come from us.”

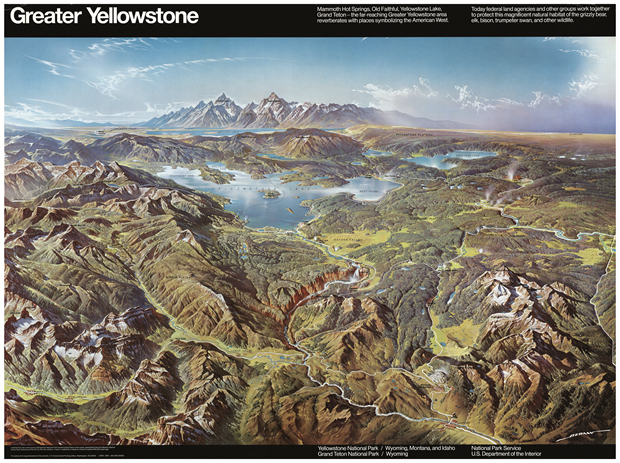

Hessler is, in summary, ideally placed to oversee our new book, a collection of 300 stunning maps from all periods and continents, which explore and reveal what these documents tell us about both our history and ourselves.

Despite his position as one of the world’s leading experts, his route to all things cartographic was somewhat circuitous. A fascination with butterflies led Hessler, who has an engineering background, to biogeography. From there he took a broader interest in cartography, his scientific background enabling him to understand the latest developments in digital representation in great detail.

“For all practical purposes, the entire globe has been mapped,” Hessler explains. “So the really interesting maps aren’t coming from developments in global positioning technology, but through the creative manipulation of huge data sets.”

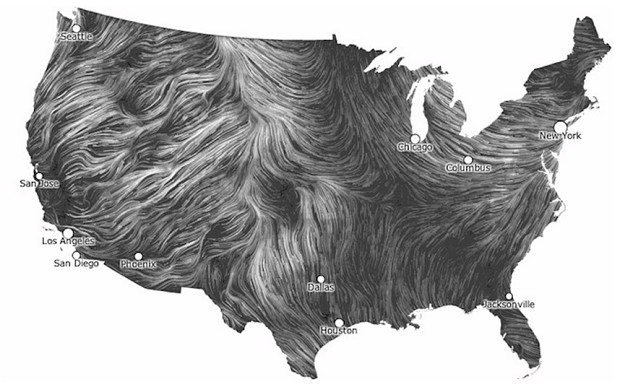

One of his favourite inclusions in our new book, Fernanda Bertini Viégas and Marten Wattenberg’s 2012 online Wind Map, takes just such a data set, from the US National Weather Service, to show, in real time, the gales, breezes and gusts flowing over the continental United States. From Hessler’s point of view, it is a masterpiece.

“The Wind Map takes something that we are so familiar with, and expresses it with such elegance and simplicity, in just black and white, with the thickness of lines expressing the wind strength.”

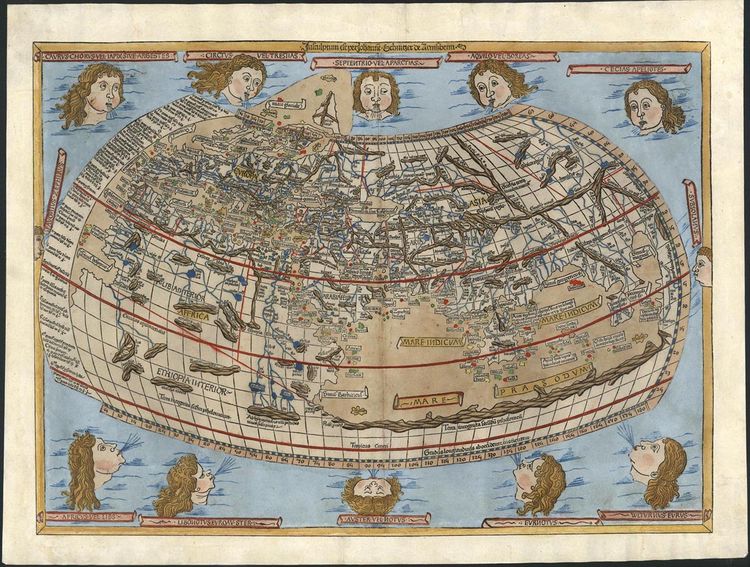

However, Hessler's capacity for technological understanding does not overshadow his interest in antique geographical documents. On the contrary, he and his colleagues have carried out mathematical studies of early maps, to understand how, say, a Roman soldier’s itinerary might have informed the maps of the ancient Greco-Egyptian geographer Claudius Ptolemy, whose maps features in our new book.

Hessler’s interest in different periods, subjects and styles of maps is captured in the new book, wherein diverse maps are laid out alongside one another, regardless of era, media or culture.

“There have been lots of books listing the top 100 maps in the world, and I wasn’t too interested in doing another of those,” he says. “It’s the contrasting, non-linear way this book is structured that attracted me to this project; the way different maps lie opposite one another highlight their various similarities and contrasts.”

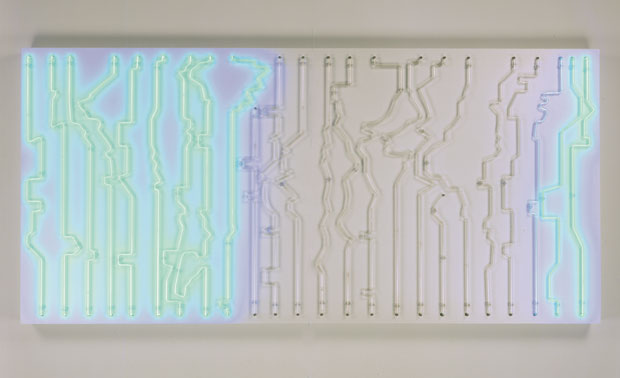

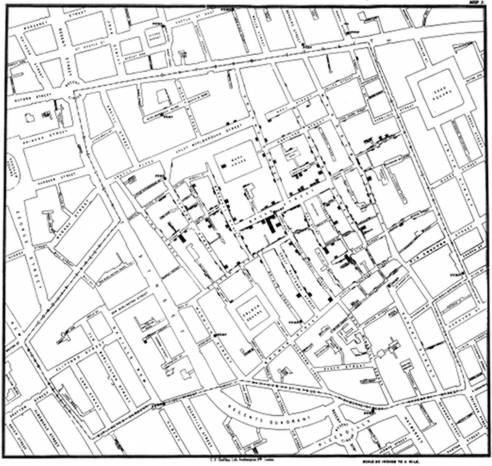

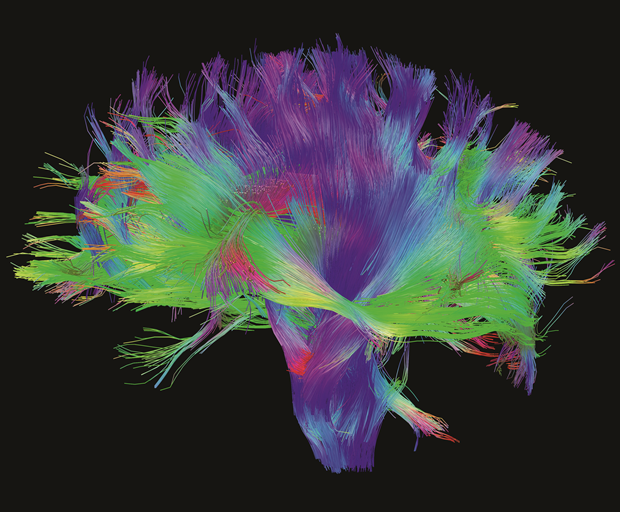

The 19th century English physician John Snow’s famous map, Deaths from Cholera in Soho, which indicated that the disease was water-borne, is on the same double-page spread as the Flowminder Foundation’s 2014 map, Human Mobility and the Spread of Ebola in West Africa, demonstrating how mobile-phone data can help inform today's public health crises; while Paul Butler’s 2010 map, Visualizing Facebook Friends, abuts the Human Connectome Project’s 2014 Mapping the Brain, a visual representation of connections within the human brain. They’re wonderfully contrasting images, yet should we really regard this brain map as a genuine work of cartography, rather than biological or medical diagram?

“Ten years ago, perhaps not,” admits Hessler. “Yet today I think we are more used to seeing networks as maps – whether that’s groups of friends on Facebook, or neural pathways within the brain.”

And if anyone's mental faculties are well suited to understanding both where maps have taken us, and where they’re likely to take us it’s Hessler, a cartographic expert unafraid of the unmapped territory.

You can pre-order our new book Map here; you can read a full introduction to the book here; and you can check back soon for more on this great title.