Why Leonardo has always kept us guessing

Last night's $450 million sale may have surprised some but uncertainty was a Da Vinci specialty

Many in the art world were surprised by the $450.3 million sale price for Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi at Christie’s in New York last night. Yet the 500-year-old painting's performance at auction was characteristically astounding for an artist who, despite a brilliant understanding of science, specialised in uncertainty.

"Leonardo da Vinci was the most imaginative and visionary artist of the Renaissance," explains our new book The Art Museum. "He was the archetypal Renaissance man, renowned in his own lifetime and since as a painter, sculptor, draughtsman, architect, engineer, inventor and botanist. Trained in the studio of the Florentine artist Andrea del Verrocchio (c.1435– 88), Leonardo (1452–1519) learned to model from close observation and to invent compositions through quick sketches. While still an apprentice he demonstrated a mastery of the new medium of oil painting and the sfumato technique (the use of soft shading instead of line to delineate forms and features)."

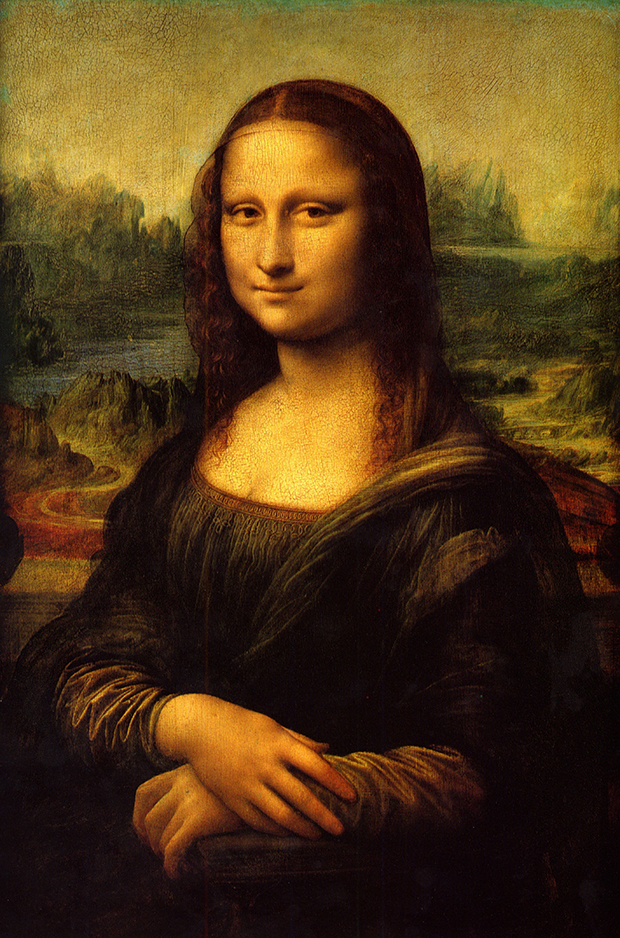

That technique, apparent in both the Mona Lisa and in Salvator Mundi is explained in greater depth by the Renaissance scholar and art historian EH Gombrich, in his canonical text, The Story of Art.

While Gombrich acknowledges Leonardo's scientific mastery, he adds that the artist found the true solution to the problem to a lifelike painting lay in the careful obscurity of the known world.

"The painter must leave the beholder something to guess," explains Gombrich. "If the outlines are not quite so firmly drawn, if the form is left a little vague, as though disappearing into a shadow, this impression of dryness and stiffness will be avoided.

"Everyone who has ever tried to draw or scribble a face," Gombrich continues, "knows that what we call its expression rests mainly in two features: the corners of the mouth, and the corners of the eyes. Now it is precisely these parts which Leonardo has left deliberately indistinct, by letting them merge into a soft shadow. That is why we are never quite certain in what mood Mona Lisa is really looking at us. Her expression always seems just to elude us."

The same is true of Salvator Mundi; indeed, the British da Vinci scholar Martin Kemp endorsed Salvator Mundi's provenance partly because of its "uncanny vortex". Though Leonardo was the supreme observer of the natural world, much of his artistry lies in the careful removal of certainty, rather than the presentation of assured facts.

To see many more Leonardo works, and to understand his place within the Renaissance more readily order a copy of The Art Museum here. For greater insight from EH Gombrich order a copy of The Story of Art here.