How prison made Isamu Noguchi a true modernist

A new exhibition at the Noguchi Museum examines the artist's time as a voluntary prisoner in WWII America

The adversities of prison life while pretty corrosive on the human psyche, can prove equally productive in contributing to the creation of great artistic endeavours. Plenty of great literary classics were inspired by life behind bars, from Oscar Wilde’s Ballad of Reading Gaol to Ezra Pound’s Pisan Cantos.

Now, a new exhibition at the Noguchi Museum in New York examines the incredible trove of work created by the Japanese-American artist, landscape architect and designer Isamu Noguchi during his time in at the Poston War Relocation Center, a wartime internment camp in the Arizona desert.

The show, Self-Interned, 1942: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center, is staged to coincide with the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066, the WWII directive that authorized the internment of Japanese citizens and American citizens of Japanese heritage living in the Western United States.

Noguchi was a New Yorker, and so was unaffected by the order; indeed, he had written to politicians, condemning these new camps. Nevertheless, in May 1942 he successfully volunteered to live within the Poston War Relocation Center, in the hope, as the Noguchi Museum puts it, “to contribute something positive to this forcibly displaced community.”

![samu Noguchi. Lily Zietz, 1941. Plaster. 15 1/4 x 7 x 9 3/8 inches (38.7 x 17.8 x 23.8 cm) [base: 10 x 7 x 7 in. (25.4 x 17.8 x 17.8 cm)]. ©The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York/ARS. Photograph by Kevin Noble.](/resource/lilyzeitz1941.jpg)

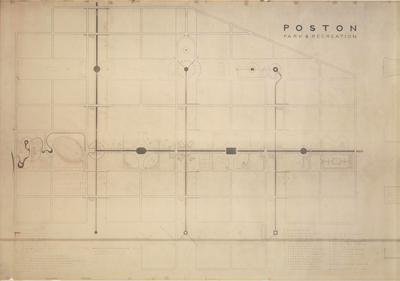

The artist’s labours were not very successful. As the camp’s only voluntary internee, Noguchi was viewed suspiciously by both the fellow prisoners and centre’s staff. He drew up plans to improve the prison environment, adding baseball fields, swimming pools, gardens, and even a mini-golf course, yet these were largely ignored.

However, while Noguchi may not have improved his prison, prison life may well have improved Noguchi. This new show, which runs until the beginning of 2018 and includes works made immediately before his imprisonment, as well as pieces drawn up in the camp, and in the years immediately after he left, in November 1942, traces the artist’s development, from his early figurative work to the modernist style for which he became known.

![Isamu Noguchi. Double Red Mountain, 1969. Persian red travertine on Japanese pine. 11 1/2 x 40 x 30 1/4 in. (29.2 x 101.6 x 76.8 cm) [base: 24 x 37 1/8 x 17 5/8 in. (61 x 94.3 x 44.8 cm)]. ©The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York/ARS. Photograph by Kevin Noble](/resource/redmountains.jpg)

This later style isn’t without clear references to the real world. 1943’s Yellow Landscape is said to refer to the anti-Japanese sentiment of wartime America, while later pieces, such as 1969’s Double Red Mountain, seem inspired by Arizona’s austere landscape. Proof that, while Noguchi’s pool and golf course never came to pass, his time behind bars was productively spent.

For more fascinating background to Noguchi’s life and some great photographic documentation of the museum dedicated to preserving his work order a copy of Stephen Shore's and Tina Barney's The Noguchi Museum - A Portrait here.