My Body of Art - Luc Tuymans on Modigliani's Nude

The Belgian artist on his love for Modigliani and Balthus and what inspired his own works Body and Diagnostic View

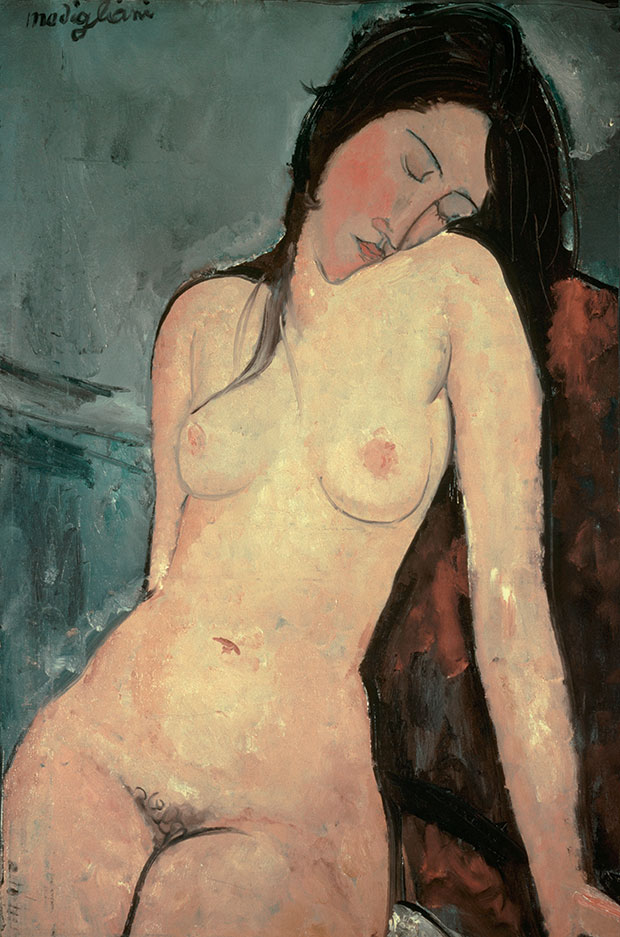

"There are several artists I admire for their depiction of the body," says Luc Tuymans during a break in the hanging of The Gap, his show of abstract art at Parasol Unit in London. "One artist I really love is Modigliani because I think Modigliani when it comes to depicting the body has the sexiest line and the most elegant forms - I always liked his nudes. He painted them in a way so that on one hand they have this element of abstraction but on the other, they are still extremely sensual. It’s the way he puts them in the frame, the way he blocks out the eyes and the gaze but still the gaze is there. For me, it’s also about how he could nearly look behind it all but still the corporeality, the warmth of the colour, the element of skin is clearly understood. A shame he died pretty young."

Tuymans is, of course, correct. Modigliani’s Nude appears to be a classical, even conventional, image of the female body. Alluring and at ease, the painting, featured in our new book Body of Art, recalls the luxurious nudes of Titian and Giorgione (Modigliani had studied in Venice before moving to Paris in 1906). Yet the painting mixes tradition with innovation. Modigliani’s model seems at once flesh and blood, and totemic. Her elongated, mask-like face hints at the Egyptian, African and Oceanic sculpture that the artist so admired, while the disjunction between the sitter’s face and body, her unusual pose, and the prominence of her pubic hair – accentuated by a brown sweep of oil paint delineating the curve of her thigh give the painting a distinctly modern edge.

Like elements of Tuymans' oeuvre, The Modigliani painting also caused some offence in its own time. It was one of the first of a series of nudes begun at the end of 1916, a number of which were exhibited at the Berthe Weill gallery in Paris in December 1917 at the only solo exhibition staged in Modigliani’s lifetime. But when local police spotted one of the paintings in the gallery window they ordered that it be removed before summarily closing the show. Despite the nude female form having long been a staple of art, the depiction of pubic hair was, even in Paris, still taboo.

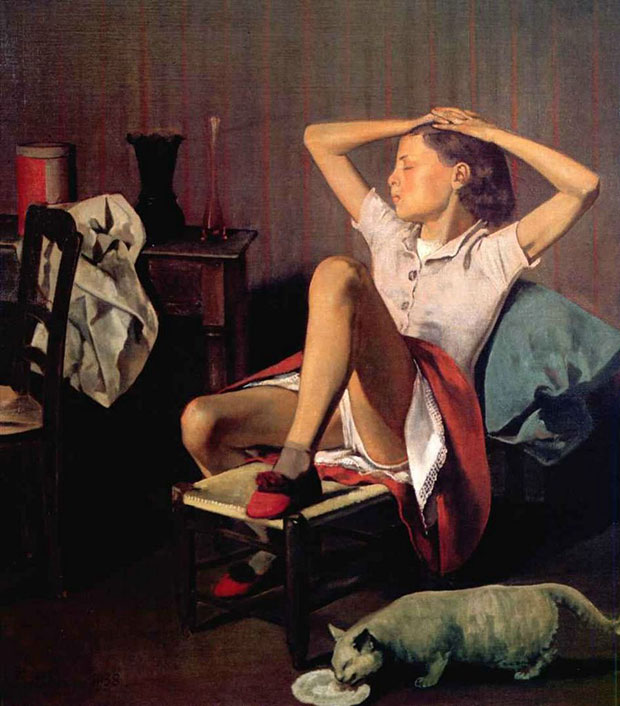

There is more than an element of the taboo in another painting Tuyman cites as inspirational. Thérèse Dreaming is one of a series of 11 paintings that the Polish French painter Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski) made with his neighbour’s pubescent daughter Thérèse Blanchard as his subject. Thérèse was around 12 or 13 when the pictures were painted, and in the paintings she seems to daydream, perhaps even sleep, captured in passivity.

"There is this real tension and it’s painted in a way which I think is quite interesting because it’s quite specific, in this sense," says Tuymans. "The very perverted imagery of Balthus and the young girl especially with her leg up and the little kitten at her feet licking the milk - you can clearly see he must have abused her."

Balthus’s ‘girl and cat’ pictures have proved troubling for many viewers because of their implied sexuality. As our new book Body of Art points out, the artist denied any erotic overtones, yet the picture’s main light source seems to shine directly between the girl’s splayed legs. Similarly, it is tempting to draw sexual allusion, as Tuymans does, from the presence of the cat lapping at its saucer of milk - reading it as representative of the artist and his carnal desires. Whether intentionally or not, Balthus’s painting forces the viewer to contemplate the line between childhood innocence and sexual maturity.

Tuymans’ own depictions of the human body have necessitated similar choices and equally unsettling reactions in the viewer. In his 1990 work Body, a painting of a doll, Tuymans confronted the idea of identity, or rather the idea of blocking out identity – The Body, in this case has no head, no genitals.

"My painting Body has become sort of iconic. Although it’s not a real body it’s a doll. (I actually still have it. The head is made in porcelain which I did not depict because it was broken but also that was not the proposition) it’s just a painting from the neck down).

"And the rest is actually cloth, so you can open it up with a zipper and stuff it and make it come alive. In Body the two lines create the impression that the body is opening up. And I used a particular medium underneath the paint to allow the painting to age much more quickly - so you have kind of juvenile cracks in the painting which sort of certifies the idea of the porcelain and the cloth as something working together. So my idea of the corporeal was pretty much tied into the idea of the object for that piece. One painting which does the opposite is Silence. It’s a sick child, but the body has faded away. Only the head is left."

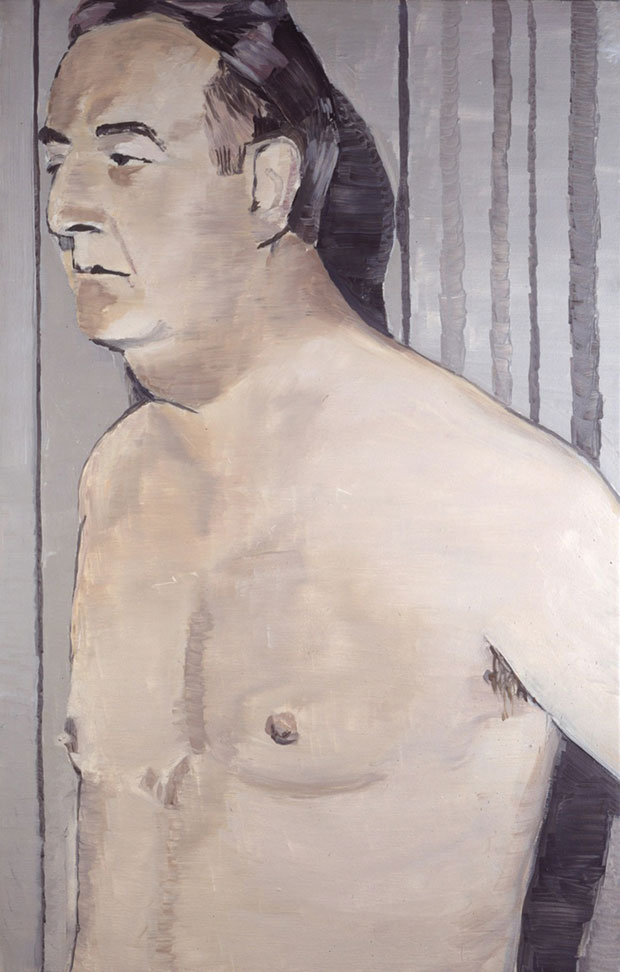

Tuymans returned to the theme of the body - this time the ailing body - in his 1992 piece Der Diagnostische Blick (‘The Diagnostic View’). The series of ten paintings feature mostly middle-aged men, taken from medical photographs, displaying symptoms of different illnesses but invoking the clinical detachment of the medical observer.

"These are probably the most naturalistic things I’ve made," Tuymans tells us. "There I’ve just shifted the eyes. This was all just taken out of medical handbooks and in order to prevent the spectator feeling any sense of empathy for what they’re looking at these people should look right through you. I applied the paint in a horizontal way so that makes it even more flat. They are very difficult to penetrate and therefore they look extremely naturalistic but at the same time because they’re so symptomatic they’re missing the real. So the body in this case is a little evasive. So it is not so much the corporeal."

For similar bodily insight, go here to read about Joel Meyerowitz's take on his beach photos; here for Bill Arning's views on Peter Hujar's photographs; here for Zhang Huan on his great work To Add One Metre To An Anonymous Mountain; and to gain greater understanding of the Body in Art and plenty more besides, buy a copy of Body of Art here.