Kerry James Marshall on Look See at David Zwirner

Buying a pin ups book and finding no black women in it was a catalyst for new work the artist tells us

Kerry James Marshall was born in Alabama in the same year that Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her bus seat for a white passenger, and his personal history is inextricably entwined with that of the African American civil rights movement. Indeed, as our forthcoming Twenty-First Century Art Book points out, "to anyone confident about how much society has changed since then, Marshall poses some uncomfortable questions."

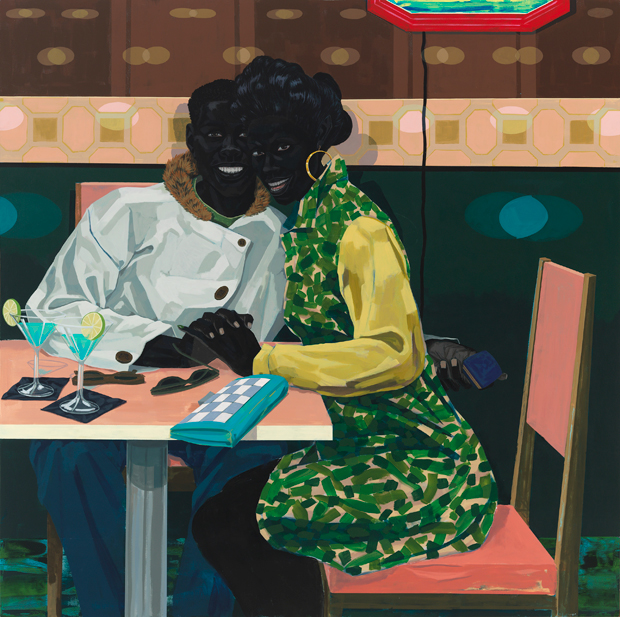

A show of new work, Look See at David Zwirner London until November 22, his biggest ever in the UK capital, leads the viewer through a series of joyful images. Look a little closer however, and it's clear that joy is tinged with some forthright comment - a bank statement here, a leather belt there, a restraining clip attached to a post - peripheral objects placed in the frame that somehow illuminate the lives of the figures within it.

Marshall's work addresses questions of identity – national, gender, but especially racial. While his work is evidence of what the artist calls a ‘vacuum in the image bank’ questioning existing systems of legitimation, it is technically complex and risky in the invention of new images that contribute to filling this vacuum. He answered some questions about it at the private view late last week.

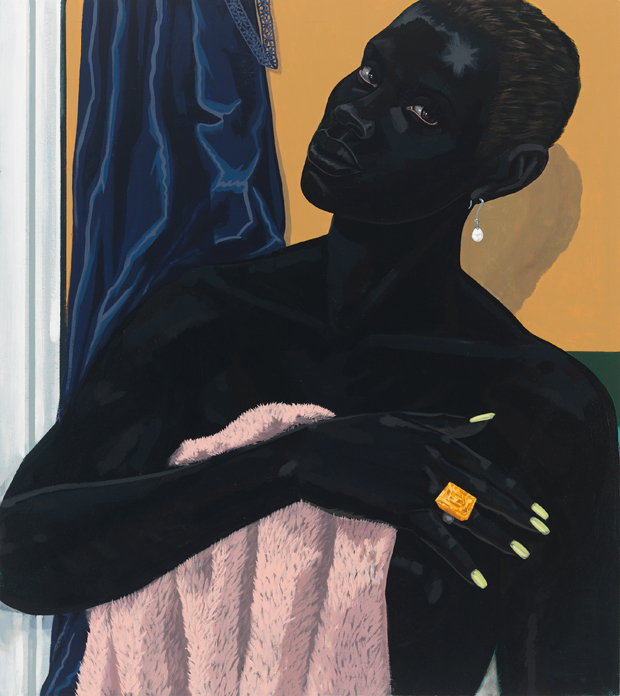

How did the series come about? In the field of representation there’s the privileged image and the marginalized image. And the privileged image takes up a lot of space in our imagination and a lot of space in our desire. And it’s often the female figure, marketing uses that male desire for female contact.

So initially I bought a book of pin ups and of course it was full of great and titillating images of girls but not one single black or Asian woman - they’re all white bodies. So that becomes the model of what desire is. So when I started making pin up images it was a response to that book or the early history of Playboy magazines, Miss Universe, all those pageants.

I was trying to figure out a way to introduce into the conversation an idealized form of the black female body but one that didn’t confirm to all the stereotypical characteristics of the white female body. So in all the pinups I did, there’s always a bit of refusal there where the body doesn’t completely surrender to the paradigm of the genre. There’s always a bit of pull back in them.

They operate on a number of levels could you expand on a few? There are a lot of levels. One of them is the way in which the things you look at and see can change your expectations of what you’d like to see next and that is always going to be a primary concern for me. One of the things I’m always interested seeing more of is images of black people. And, in particular, seeing images of black people that don’t always conform to expectations we have.

What I’m trying to do with these is to allow the figure, the subject in the picture, to have a kind of self-possessed quality. They’re sort of indifferent to the spectator, sometimes totally indifferent, but at the same time I try to create this aura of desire around the figure.

You seem to be interested in what the picture does, how it performs and what it says about its relationship to the history of pictorial representation… Absolutely. I’m not a gestural artist, I’m not interested in the art per se but I’m really interested in structure and the way in which these figures and the idea around the figures fits within the structure and how it’s evolved over the history of painting, from the renaissance all the way up to modernist and post-modernist work.

One of the things we always expect to see is the image somehow associated with some sort of sociological circumstance or somehow traumatized or impoverished. So I’m always interested in looking at ways to shift those perceptions.

__And you make the figures extremely black, there’s a kind of spectacular presence there. . . __ They are extremely black and that is sensational enough to me so I don’t need to add another layer of energy. I’m always looking to enhance the spectacularity - if that’s a word - of the presence of the figure.

Is that blackness an aesthetic choice or an identity choice? It’s all those things wrapped up in one thing. It answers the challenge that blackness has always been stigmatized. Historically it’s a stigmatized condition. And it’s something that most people, even a lot of black people flee from - that density of darkness. They kind of recoil because it’s always been stigmatized to be dark. In western context darkness is evil. In colonial and imperial context blackness or dark skin was always weak, powerless, subjugated.

So over centuries you develop a psychology that even for a person who has black skin it causes you to recoil from it. And so, for me, the antidote to that is not further distancing from the extremity of the blackness, it’s a total investment in it. That’s the antidote. And when you see this all the time and they’re no longer a spectacular, sensational thing then it becomes part of your everyday expectation and it’s normalized and no longer stigmatized.

Then the challenge, since these images don’t circulate so smoothly through the market place - and the art world is a market place! - is to figure out how to make these images captivating at the same time so that they can move if not slowly through the commercial system at least find their way into the institutional art world. Look See runs at David Zwirner London until November 22. For more on Kerry James Marshall and the artists who have driven a hugely prolific period for the visual arts since the start of the new Millennium check out The Twenty-First Century Art Book.