What do you see in Georgia O'Keeffe's flowers?

How did the painter take this ultimately feminine symbol and transform it into the acme of modernist art?

Flowers are perhaps about as feminine an artistic symbol as you can get. And yet, not all artist's flowers are the same, as a brief glance at Luc Tuymans' Orchid, Matisse's Water Lilies and Van Gogh's Sunflowers will tell you. In the American painter Georgia O'Keeffe's work, the plant's reproductive organs take on a new significance, as Randall Griffin, US art history professor and author of our new Phaidon Focus book on the artist, explains, in a chapter entitled The Question of Gender.

"It now seems abundantly clear that, in spite of her vehement denials, O'Keeffe meant some of her paintings (not just the flowers) to look vaginal," Randall writes. "Works such as Abstraction Seaweed and Water - Maine and Flower Abstraction overtly allude to female genitalia."

This seems quaint in our current age. However, as Griffin makes clear, O'Keeffe did not intend to offend or titilate her viewers, but rather set herself apart within the masculine world of 20th Century American painting.

"O'Keeffe's aim was to distinguish herself from her contemporary male artists by producing paintings that would seem both audaciously sexual and innately feminine," Griffin writes. "Moreover, the feminist writer Lisa L. Moore has argued that O'Keeffe's flowers should be seen as part of a lesbian tradition extending back to the eighteenth century, since some evidence suggests that O'Keeffe had several brief sexual affairs with women. According to Moore, these included Rebecca Strand (wife of Paul Strand), in 1929, when the two spent five months together in Taos, New Mexico, along with Mabel Dodge Luhan, that same summer in Taos. O'Keeffe may have also had an affair with Maria Chabot, who oversaw the renovation of O'Keeffe's Abiquiu hacienda between 1945 and 1949.

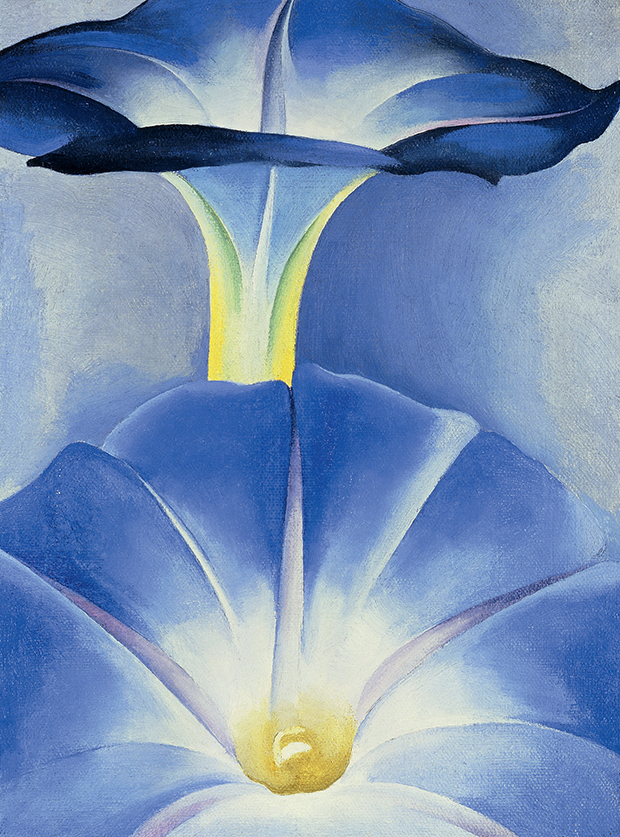

While this reading of O'Keeffe's painting ties in with numerous biographical details, it was not an interpretation that she herself encouraged "So what explains O'Keeffe's indignation over the erotic readings of her work?" Griffin goes on. "First of all, many of her flower paintings do not resemble vaginas or penises, for instance Blue Morning Glories and Jimson Weed, and thus possess no sexual frisson. But, even for those that do, such as her iconic depictions of irises, she would probably have thought such interpretations reductive caricatures. Her portrayals of flowers are about various things, above all morphology and colours. Always a formalist at heart, O'Keeffe said, in a statement that echoes the ideas of Dow, 'The subject matter of a painting should never obscure its form and color, which are its real thematic contents.'

This rejection did not prevent later women artists from championing this vaginal reading. "Feminists in the 1970s, including the artist Judy Chicago, embraced O'Keeffe as a trailblazer for their cause," Griffin explains. "Chicago's The Dinner Party presents a feminist pantheon of women poets, novelists, rulers, goddesses and artists from across the millennia. The names of 999 women are noted on floor tiles and an additional 39 women, including O'Keeffe, are given their own place settings with vaginal ceramic plate 'portraits'. The feminist co-option of her art enraged O'Keeffe, who stated emphatically, 'I am not a woman painter!' By this time, she was already firmly ensconced in the pantheon of American art - as strongly as Winslow Homer (1836-1910), Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and Edward Hopper (1882-1967) - and did not want her achievement typecast or marginalized in any way.

"Yet, in spite of O'Keeffe's negative reaction to the feminists' views, she was an exception in her day and was continually made aware of her gender in an art world where galleries, schools, museums and criticism were dominated by men. O'Keeffe was a member of the pro-suffrage National Women's Party and once said, 'I believe in women making their own living. It will be nice when women have equal opportunities and status with men so that it is taken as a matter of course.' In many ways her life incarnated the message of Virginia Woolf's iconic essay A Room of One's Own.

However, Griffin believes O'Keeffe was never a feminist or overtly political artist. "Indeed, she disdained political art, which she found illustrative and lowbrow, and she would have agreed with Oscar Wilde's 'Art for Art's Sake' statement that 'All art is quite useless'. When the US was reeling from the Great Depression, the editor of the Marxist journal New Masses accused her of insensitivity as an artist to the needs of the poor. In a public debate with him, she defended herself by saying that, as a respected and successful artist, she offered a model for women in general. The critics Anna Chave and Anne Wagner have argued convincingly that O'Keeffe altered her art in the 1920s, turning to the flowers so that she could explore the female body and its experiences. O'Keeffe herself said that she was 'trying ... to do painting that is all of a woman'. For Judy Chicago and others, O'Keeffe's great achievement was that she created a fearlessly candid - though metaphoric - representation of the female body, one entirely different from the tradition of female nudes painted by male artists for a male audience. In considering the female body from a woman's perspective, and openly exploring female sexuality, O'Keeffe's approach presaged the art of Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse (1936-1970), Ana Mendieta (1948-1985) and a host of others. So, in the minds of many, whatever her politics, O'Keeffe offered women artists a self-empowering model of female independence.

"But there is no denying that the flower pictures also perpetuated stereotypes about women artists as flower painters, and also reinforced the view that they personify sensuality, feeling and fecundity and are inherently mysterious creatures. This conception of feminine otherness continues to appeal today; O'Keeffe's authority still has much to do with the perception that she was an avatar of femininity. Thus, in her flower paintings, O'Keeffe simultaneously exploited long-standing gender associations with flowers and recast the genre to present herself as an uninhibited 'modern' woman and vanguard artist."

Intrigued by this brief extract? Then go here to pre-order the book, the latest in our Phaidon Focus series of accessible, up-to-date, authoritative, enjoyable and thought-provoking books on internationally renowned modern masters. You can also pre-order it as an iBook here.