From Book to Bid – Mapplethorpe's Calla Lily

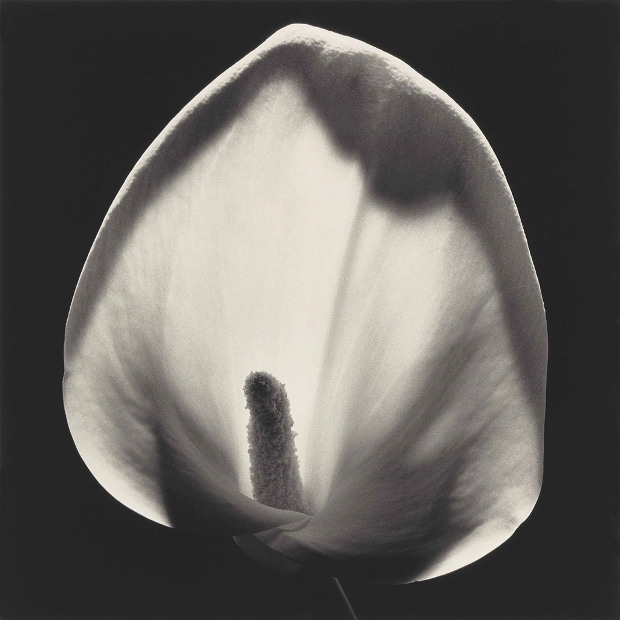

Read how this 1984 study of a Calla Lily, for sale at Christie's, expresses the deep interplay in Robert's work

It’s sometimes said that Robert Mapplethorpe photographed flowers as a substitute for, or an antidote to, his more explicit material. However, a careful reading of the artist’s life proves that this may not be wholly true. As his former assistant Dimitri Levas recalls in the introduction to our new book, Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers, the flower pictures actually came first.

“When Robert was first given a Polaroid camera in the early Seventies by his friend John McKendry, the former head of prints and photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Levas writes, “he taught himself about light and exposure by photographing flowers.”

Any visitor to Photo London will be able to view many pictures taken by the late photographer after he mastered the medium. There are Mapplethorpe nudes and pictures of his friends, such as Patti Smith, in among the fair’s stands. Mapplethorpe, who died in 1989, is having something of a moment again right now. However, the work that crowns Christie’s accompanying photography sale in London tomorrow Friday 20 May, is his 1984 image of a Calla Lily.

So where do these floral images fit into his greater body of work? Though he went on to shoot sex club habitués, body builders, anonymous nudes and celebrities, he continued to take flower pictures throughout his career, perfecting the photographic expression of so straightforward a source of biological beauty.

Unlike Georgia O’Keeffe, Mapplethorpe never denied any sexual inference in his floral images. However, he, unlike O’Keeffe, created both sexually explicit pictures and flower images; though it’s hard to deny a link between the two, it’s also clear both types of images were distinct. As Levas puts it “it seems appropriate to think of the flowers within the realm of Robert’s fundamental visual language.”

In our book, Levas describes a typical Saturday in the 1980s, while working for Robert: “I would get up early and go to the flower market on Twenty-eighth Street, which opened at the crack of dawn. I would pick out the flowers that had the most architectonic shapes and those with the most perfect form. I would let myself in to Robert’s loft on Twenty-third Street, put them in water, and then go to the flea market on Twenty-sixth Street to hunt for treasures. I would go back to Robert’s to have my lunch, while he had his breakfast, and show him my flea-market finds, which he would often buy off me. At around three or four in the afternoon he would photograph what I had brought that morning.”

Interestingly, Mapplethorpe did not value flowers beyond their use in his photography “If say, at the opening of an exhibition he was given a flower arrangement, he would photograph it and discard it almost immediately,” Levas recalls. “The same was true with flowers acquired strictly for the purpose of making photographs.”

Rather than seeing them as interior design dressing, Mapplethorpe was drawn to his flowers partly because of their straightforward beauty, but also because of their historical connotations.

“What makes Robert’s flower pictures so successful is the interplay of the sensual and the art historical reference,” Levas writes. “Robert was well grounded in the role of flowers in the history of painting. Here the sensual and the prurient are intertwined. Robert’s flowers are not always about sex, but they are always sensual.”

The photo in the Christie’s sale, which appears on page 315 of Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers captures this interplay just so. The petal appears to have the kind of patina and curves of a classical sculpture; it’s tempting to imagine that this is the kind of image an ancient Greek artist might make, if presented with a Hasselblad and a Calla Lily. Yet the flower’s stamen – the plant’s reproductive organ – lies at the picture’s centre. It isn’t overpowering, but it isn’t denied either. Robert’s erotica succeeded by making difficult images beautiful; yet with the flowers this trick seems to be reversed. Here, he makes beautiful things difficult.

For more on this Christie’s lot go here. For greater insight into how to buy at auctions, get a copy of Collecting Art for Love, Money and More. And for a deeper understanding of this important photographer’s work get Mapplethorpe Flora: The Complete Flowers here.