Inside Mark Bradford's US pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Why the LA artist is drawing on classical mythology, Marilyn Monroe and prison reform in his installation

How do you represent your country, when you don’t quite feel at home? That’s a question the Los Angeles artist Mark Bradford had been asking himself in the run-up to this year’s Venice Biennale.

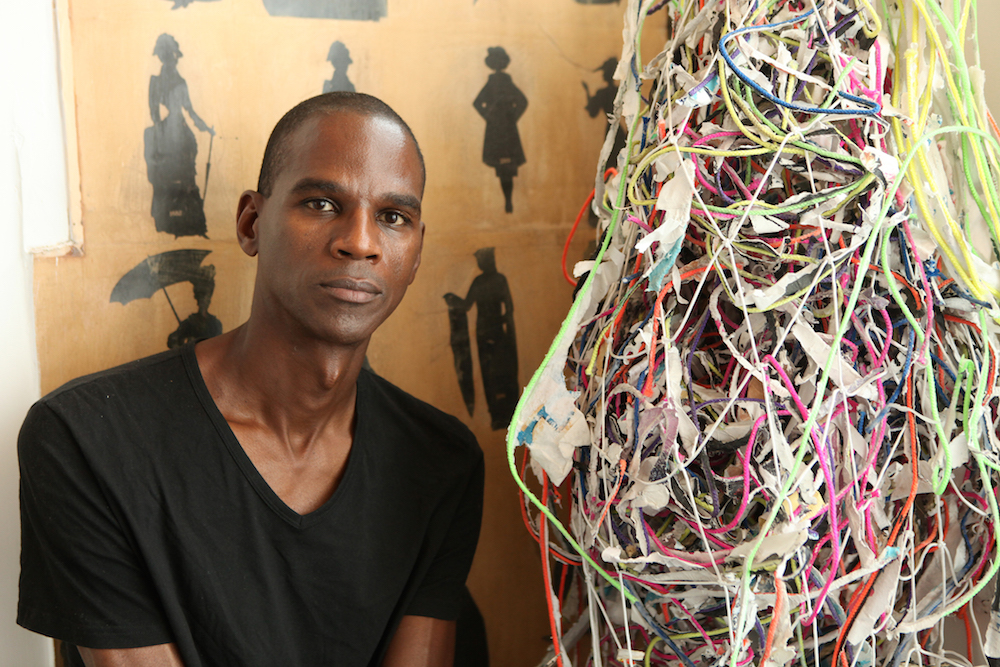

Bradford, a tall, black, gay artist, born into modest circumstances in Los Angeles in 1961, is a self-described liberal and progressive thinker. He visited the White House during the Obama administration yet now, as he told the New York Times recently, he no longer feels represented by his government.

In response, he has installed a critical series of works into the Palladian-style pavilion, which Bradford described as a state-owned, “Jeffersonian” space. “I wanted it to feel like a ruin, like we went into a governmental building and started shaking the rotunda and the plaster started falling off,” he told the paper. “Our rage made the plaster fall off the walls.”

The show, entitled Tomorrow Is Another Day, is no simple work of agitprop; there’s plenty of delicate artistry, humanity and classical reference points in there.

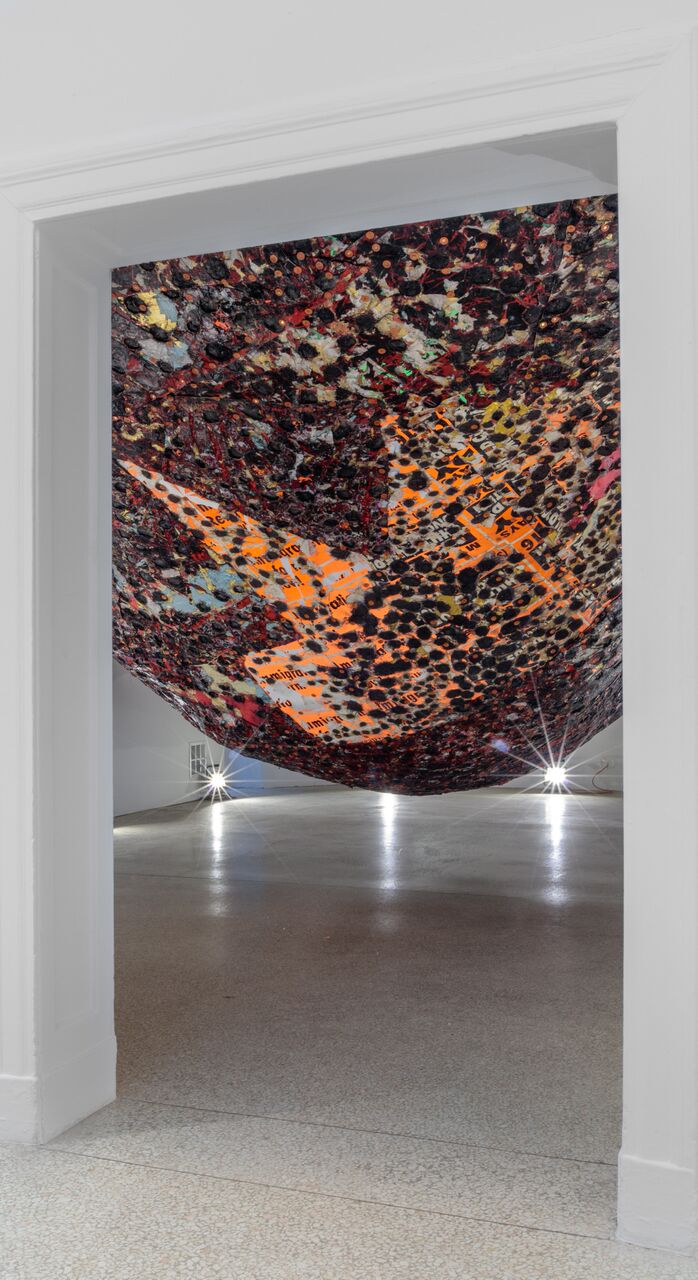

Inside the building a rash-coloured, pock-marked canvas hangs into one of the galleries, pushing visitors to the margins. Entitled Spoiled Foot, the piece refers to the Greek god of craftsmen and sculptors, Hephaestus; in one version of the Greek myth Hephaestus is cast out of Olympus after attempting to protect his mother, and breaks his foot. The tale resonated with Bradford; he was raised in a boarding house by a single mother, who was simultaneously trying to build up her beauty and hairdressing business.

Bradford worked alongside his mother during his early life, and is well-known for incorporating beauty-parlour materials into his works. In a series of black and purple paintings, he has pasted perming end papers in among the paint.

Hair and beauty imagery is also apparent in a mixed-media sculpture, Medusa, which seeks to re-evaluate the classical monster (Bradford draws on accounts of Medusa as wronged by Poseidon — not horrifying, but beautiful and powerful), while also paying tribute to women and his mother.

The pavilion’s central rotunda there’s a site-specific installation, Oracle, that both brings to mind the flaking billboards of LA and elsewhere, but also the ancient dwellings of classical soothsayers.

“He transports us back in time to the ancient grotto, a site between cave and altar, between nature and culture, where oracles would deliver profound truth and predictions,” explain the US pavilion’s organisers.

There’s also a video work, Niagara, from 2005, wherein Bradford’s former neighbour, Melvin, enacts Marilyn Monroe’s role in a scene from the 1953 thriller of the same name. The old movie, Monroe’s first starring role, is a tale of betrayal and murder in upstate New York, and Bradford’s recasting of the starlet’s role raises poignant questions of race, sex and criminal culpability.

Bradford continues this final theme, beyond the Biennale’s grounds. The artist is launching a long-term social programme, Process Collettivo, as part of his Venice show, in conjunction with a local prison charity, which aims to foster a deeper understanding of the problems within the penal system, and help rehabilitate local prison inmates and ex-offenders.

A store in the city’s Frari district will offer artisanal goods made by Venetian inmates, and also serve as a resource and support centre for former prisoners; all proceeds from the sales towards the local charity, Rio Terà dei Pensieri. It’s a fitting souvenir stop for any Biennale visitor, yet Bradford has made sure this place will stay open for six years - long after the crowds have left the Giardini.

For more on Venice’s place within contemporary art history, get Biennials and Beyond. For more on Mark Bradford look out for our forthcoming monograph, due out later this year.