A Movement in a Moment: Precisionism

How photography, the Ford Motor Company and Cubism shaped America’s first truly modern art movement

In 1927, the American architectural photographer Charles Sheeler was commissioned to photograph the Ford Motor Company’s new industrial complex, built along the Rouge River in Dearborn, Michigan. Sheeler was not only an accomplished photographer, he was also a keen painter. He travelled to Europe during the first decade of the 20th century, and was familiar with modernist developments such as Cubism. Having photographed the Ford plant, Sheeler returned to the subject repeatedly, creating a series of paintings from his pictures in way that combined Cubist motifs with elements we might more closely associate with Futurism and Photorealism.

Sheeler’s clear, accurate, straighforward take on the modern world, also apparent in the paintings of like-minded US artists such as Charles Demuth, is now known as Precisionism and is, perhaps the first trully American modern art movement.

“As the 1920s took shape, a group of North American painters responded to the expanding urban and industrial landscape around them with a style that combined the geometric scrutiny of Cubism with the exactness of photography,” explains our book Art in Time. “In Europe, the Futurists proclaimed the triumph of technology over nature, but in North America the artists similarly inclined to glorify the industrialised modern world were not formally organised and had no manifesto to bind their beliefs. Precisionism, a term coined in 1927 by Alfred H. Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, came to define their sharp, clean, imposing aesthetic.”

Unlike Futurism, Precisionism was less concerned with overtly praising the beauty and brilliance of modern technology, and was more interested in mimicing its exacting accuracy, even when depicting some of the industry’s less lovable aspects.

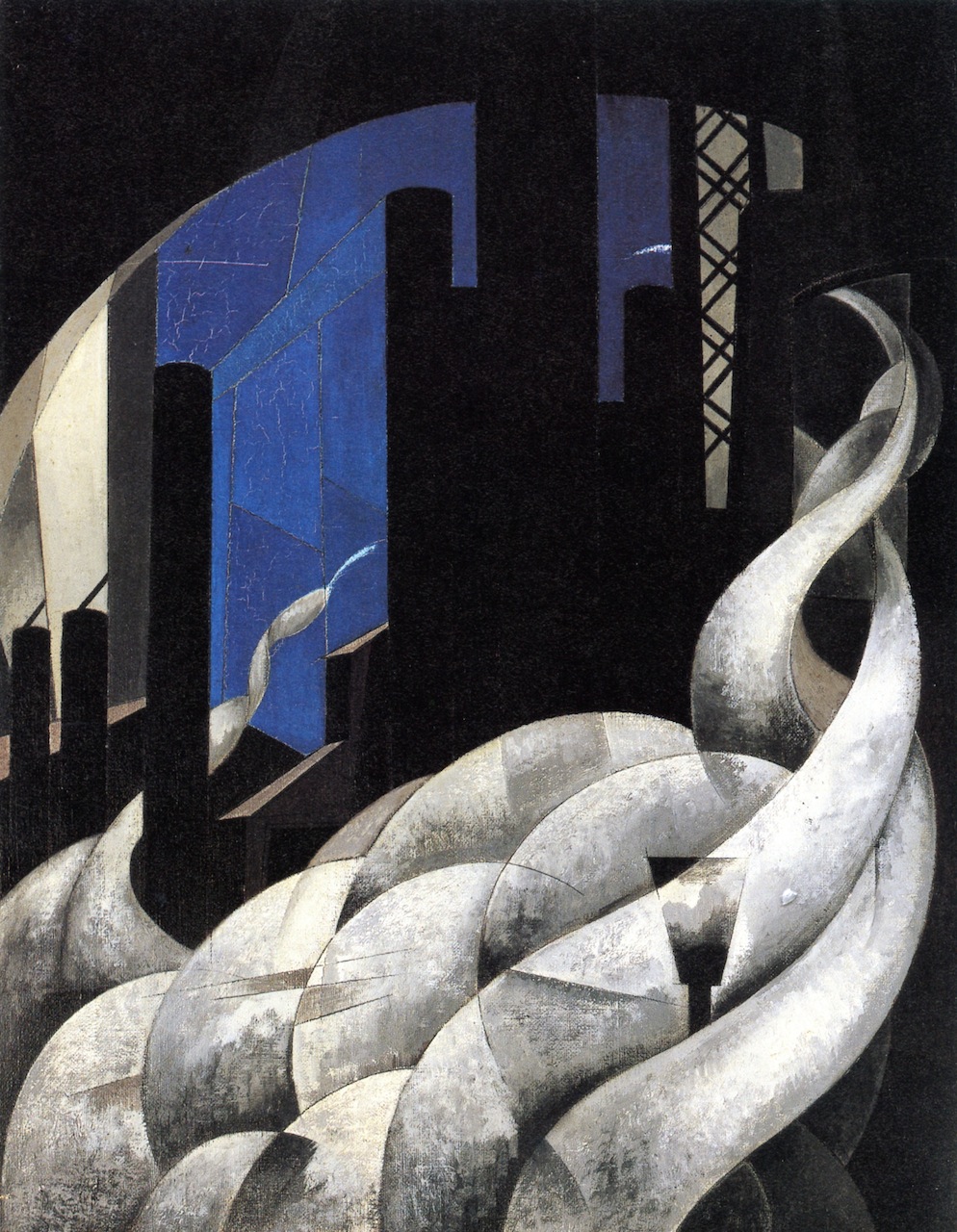

“One artist to engage with both American and European strands of modernism was Charles Demuth,” Art in Time explains. “In his Incense of a New Church, the Lukens Steel Company’s steel yard in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, is transformed into a dramatic, mystical monument. Grey-white smoke envelops a skyline of towering chimneys that stand proudly, in rigid refusal of the dusk blue sky behind them. Demuth’s title is ironic – mocking American religiosity by conflating it with the industrial – but any intended satire is thwarted by the powerful, ominous beauty of the factory.

“Though American modernists inherited much from Cubism, Incense of a New Church demonstrates the Precisionists’ more contained approach. Cubism often complicated the perception of an object by fragmenting it, whereas Precisionism sought instead to simplify and distill, rendering a reality straight from the assembly line: rigid, unambiguous and – as the movement’s name indicates – precise. For this reason, the Precisionists were sometimes referred to as the ‘Immaculates’, and their style was labelled ‘Cubist Realism’.”

While Precisionism was not the best-known of artistic movements, it did include one world-famous US painter among its number for a brief period. “Known predominately for her paintings of abstract flowers, and the desert of the American south-west, Georgia O’Keeffe moved to New York in 1918 and began a series of paintings with the city as subject,” explains Art in Time. “She rendered the metropolis in angular, grandiose splendour, as in New York with Moon, in which a cluster of buildings create a jagged skyline, crowding the distant moon and framing the vivid lights of the street below. O’Keeffe’s austere, windowless structures suggest an impersonal city – as isolating as it is magnificent.”

Today, O’Keeffe’s skulls and lilies are more popular than her cityscapes, yet the work of the Precisionists lives on. Demuth is sometimes cited as a pop-art precursor; Sheeler and other artists’ willingness to engage with photography preempts photorealism; their pin-sharp rendering of an industrial landscape is echoed in the Dusseldorf School; while anyone today who wishes to express the awestruck majesty of the modern America must know that Sheeler and co got there first.

For a deeper understanding of the Precisionists place in American art get Modern Art in America 1908–68; for more on O'Keeffe get this book; and for more on this movement and many others, get Art in Time.