Gombrich Explains Renoir

On the French Impressionist’s birthday a look at why his paintings have divided art lovers for over a century

Early last summer the US activist and professional agitator Max Geller submitted a petition to the White House, calling on President Obama to have all works by the French painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir removed from US national museums. The document, written by the self-styled leader of the 'Renoir sucks at painting' movement, boasted just 15 signatories, (and one of those was Geller's). Yet the accompanying protests – mounted, it seems, only partially in jest – against “Renoir's treacly, puerile paintings” nevertheless gained a great deal of press coverage across the world.

And while they may not have gone so far as to even think about signing his petition, some commentators sympathised with Geller’s critique of Renoir. The artist, who was born on this day, 25 February, in 1841, is, in some sense, a victim of his success. His subjects, such as young lovers and city crowds, although unpopular during his early career, have been adopted by less-talented Sunday painters, and appear, to the untutored eye, cloying, while his purposefully inexact painting style, which was revolutionary at the time, is in Geller’s and others opinion, not a sign of his skill, but a demonstration of the Frenchman's shortcomings.

But to get a better idea of how to regard Renoir, and a way to appreciate his paintings today, it's always wise to turn to the brilliant art historian EH Gombrich, and his well-known book, The Story of Art. Gombrich examines Renoir's work in a chapter of the book subtitled Permanent Revolution. Here the historian looks at how rising industrialism undermined artists' positions, and how artists responded.

Renoir was of course, an Impressionist, one of a group of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century painters Gombrich says not only shocked contemporary audiences with their inchoate, misty style, but also by their unusual choice of subject matter, such as railway stations, working harbours or bustling city streets, which, up until then, had not been regarded as suitable subjects for artists.

When Renoir chose to paint a party crowd, he did not settle on a high-society gathering such as his fellow countryman Jean-Antoine Watteau had painted 150 years earlier. Instead, he chose the ordinary people of suburban Paris, drinking, dancing and eating at an outdoor restaurant. What’s more, he worked hardest on certain portions of his subjects, leaving other details quite underdeveloped.

“Only the heads of some figures in the foreground are shown with a certain amount of detail, but even they are painted in the most unconventional and daring manner,” Gombrich writes. “Beyond, the forms dissolve into sunlight and air.”

However, as Gombrich points out, “we realise without difficulty that the apparent sketchiness has nothing whatever to do with carelessness but is the outcome of great artistic wisdom. If Renoir had painted in every detail, the picture would look dull and lifeless.”

Look again at Dance at the Moulin de la Galette from 1876, and we can see that, yes of course, the less detailed parts add to the painting’s strength in a way that Renoir and his fellow artists anticipated. As an event, this simple scene is closer to us today than some aristocratic scene of a century earlier, even if our mind shades in certain details for us.

As Gombrich explains, Renoir and co. “knew that the human eye is a marvellous instrument. You need only give it the right hint and it builds up for you the whole form which it knows to be there. But one must know how to look at such paintings. The people who first visited the Impressionist exhibition obviously poked their noses into the pictures and saw nothing but a confusion of casual brushstrokes. That is why they thought these painters must be mad.”

Today, many still see a confusion of casual brushstroke. Yet with the aid of historians such as Gombrich we can understand the majesty of this irresolute style, this ordinary, joyous subject matter, and painter’s rightful place within the artistic canon.

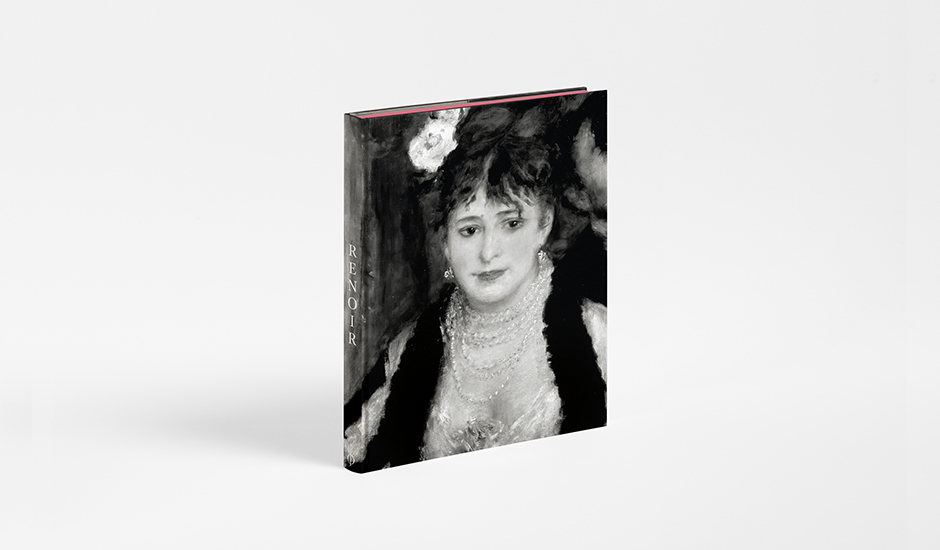

For more on Renoir’s position within the greater sweep of artistic history, order a copy of The Story of Art here. For greater insight into this painter, as well as the chance to own some wonderful reproductions of his work, buy a copy of our new Renoir monograph, here.