How the (rest of) the world went Pop

A new show at Tate Modern looks at Pop Art from around the world - curator Flavia Frigeri talks us through it

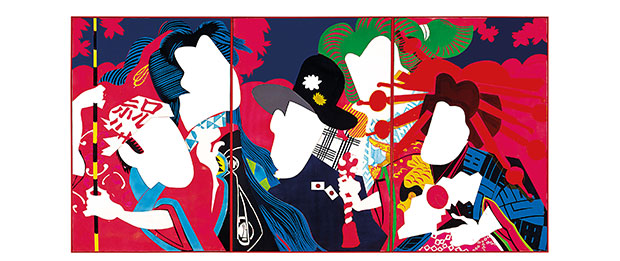

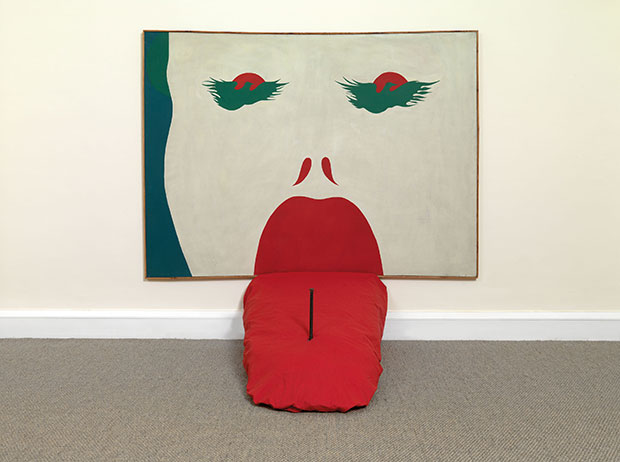

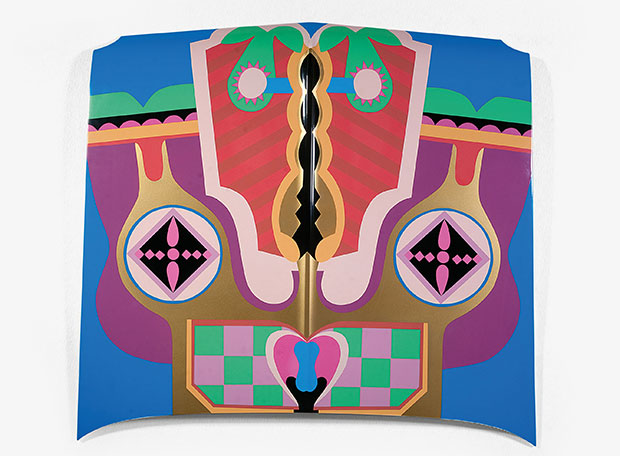

From Latin America to Asia, from Europe to the Middle East, from canvases to car bonnets, protest art and even folk art the Tate's new show, The World Goes Pop, connects the dots between a body of art made around the world during the 60s and 70s - much of which has never been seen outside its country of origin and some that's never been seen since it was originally created.

The exhibition shows how Pop art was not just a celebration - or critique of consumer culture in the West but a subversive international language of protest as relevant today as it was in its original era. We caught up with it's co-curator, Flavia Frigeri as it opened in London.

How would you describe the show to someone who's expecting a grouping of Hamiltons, Warhols and Lichtensteins? I would say that it’s nothing they expect and there is a Pop Art they’ve never seen and would never think exists. But it’s as exciting as the one we’re most familiar with. It’s bright, it’s colourful, it’s engaging - it’s everything we think about Pop Art but just has other shades to it.

So is it a reaction to pop or a previously unseen side of Pop? It’s not necessarily a reaction - in most cases the artists in it many of whom were working in the Eastern bloc or under dictatorships - didn’t know Pop existed. So they were just reacting in many cases to what was the gestural tradition usually associated with the Fifties. It’s more a reaction to American imperialism - so not the movement itself but what America stood for.

A couple of reviewers have called it revisionist, lamenting the lack of Warhols and Hamiltons It wasn’t our intention to do something revisionist – it’s an ugly word. But I think it’s the duty of a place like The Tate to not always rehash the same story. It’s our duty to say there was another story out there and people may not always want to accept it because they just think Pop is Warhol and good for them! But I think it’s interesting to show that Pop is not just that!

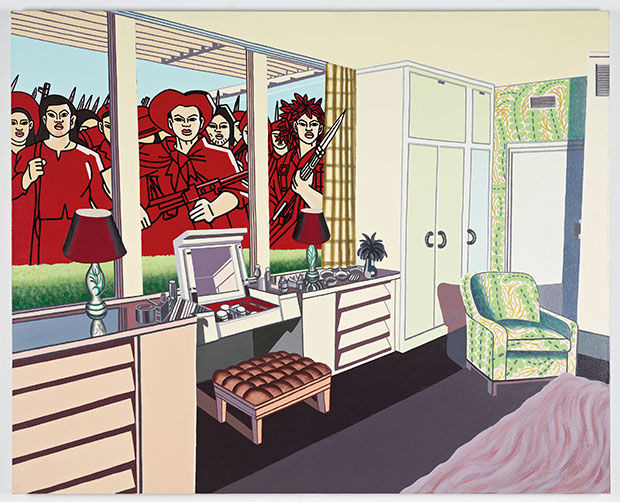

We all know the story about the CIA funding abstract expressionism but was there an element of America doing the same with Pop? If so, were the eastern bloc artists in the show perhaps aware of, and responding to, this? Traditionally it’s always said that Rauschenberg’s victory in 1964 at the Venice Biennale is what triggered the pop movement. That was the year when Oldenburg, Warhol - all of them - were part of the American Pavilion and then the great prize was awarded to Rauschenberg so it’s said it was masterminded by the CIA, a sign of something that had been politically maneuvered. Some artists did cite Rauschenberg’s victory as something that triggered them towards a language but I don’t think they necessarily saw Pop art as the language. I think it was more the themes they were addressing with this language that really became their response to American imperialism. It’s their engagement with events like say the Vietnam War that really pushed their Pop forward.

Did you set up a set of new Pop parameters to keep some shape to the exhibition, to stop it becoming too baggy? Paradoxically we didn’t really set any parameters. Because it’s very hard, it’s such an unknown territory, it’s so unknown. So what we really did was travel to all of these places, meet with all the artists, try and understand what it meant for all of them. Bear in mind that the majority of these people were shown in the 1960s but then a lot of them turned to different careers. So they’re not known outside of Argentina, Brazil and so on which meant that this wasn’t something we could research from our desks in London. So a lot of it came from us really doing our homework on site and it took us a couple of years before we actually gathered a better sense of what was going on in different places to be able to affix parameters or guidelines for what we were trying to do.

One of the brilliant things about American Pop art is that you never know if it’s complicit or if it’s critical of the consumer society, did you find this to be the case with the artists you came across on your travels? We noticed the pattern that pop was very political. With this show it became very clear from the get go that is was definitely a very critical language. So that in itself was the first guideline. So we knew the subversive, the political element was important and was something we wanted to draw out.

And then gradually, as we got a better grasp of which works we wanted to include, we started to think about what themes they were addressing. And how they could speak to each other. But it was a process that took us years to really narrow down. We had lists that were far longer than we could ever include and far more themes than we thought we could ever address. It was a process of accumulation and then stripping down. And then, organically, we built up our argument.

That importance of spending time in situ with the art brings to mind an idea of the curator almost as excavator doesn’t it? Yes, you do feel a bit like an archeologist. In many ways it’s a dream project for a curator because you rarely excavate in a way where you can completely rethink something. It’s something that you embark on and you don’t really know what you’re going to find. The excitement of finding great things that have never been seen is incomparable.

Finally, the inclusion of folk art is really very interesting. As a form it’s pretty much the antithesis of Pop - not mass-produced, nor garishly coloured! Yes, we actually came to the folk stuff halfway through the project. Those works are part of our collection and we always had them on our list but we didn’t for a long time know how to think about them. Those in many ways didn’t fit any of the pop parameters but they were an interesting spin on what Pop means and it was only when we found them that we realized that there was this whole stream of folk going on.

It was incredibly interesting to find Beatriz González’s work and Raúl Martínez’s work and to see what a Cuban artist was doing in relationship to the context he was working with - also taking that idea of serialization and repetition to the extreme. I mean, Warhol does it with the Marilyns and Martínez does it with the fathers of politics in Cuba. It’s such a contrast. That’s a good example of something that came organically out of the works rather than us saying, wow, we should do a folk section!"

The World Goes Pop is at Tate Modern until January 24. You can learn more about Pop in the books: Pop and Pop Art.