In conversation with Melvin Edwards at Frieze

The veteran American sculptor discusses abstraction, racial politics and finding his place in the modern canon

Frieze Masters, the art fair that offers a contemporary take on historical art, is a wonderful place to catch up on the various schools and movements. Some displays confirm our beliefs, while others prove that a straightforward, historic reading of 20th century art can only take us so far.

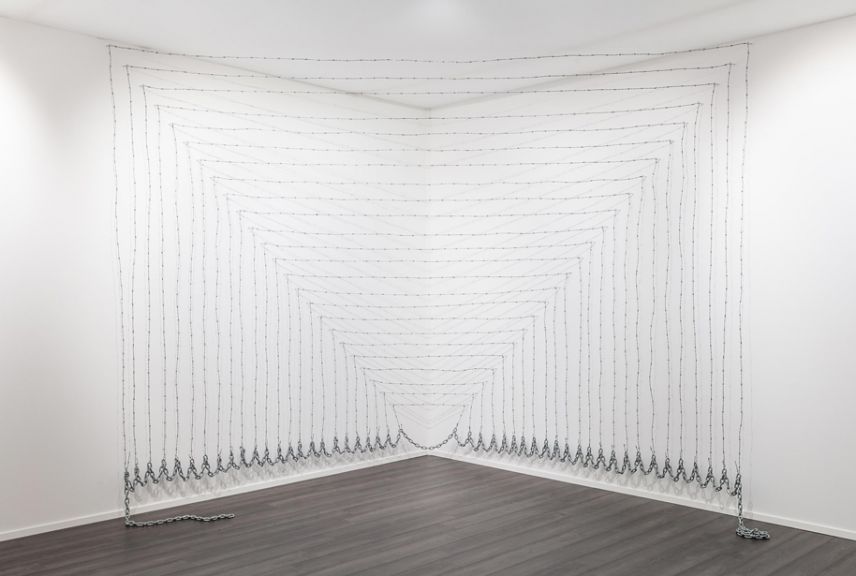

Take, Melvin Edwards’ exhibition at Stephen Friedman Gallery’s stand (G15). The display consists of a large, angular barbed-wire and chain work, conceived in 1970 though executed for the first time at Frieze alongside, a series of twelve untitled watercolours from 1974 which also use chains and barbed wire as stencils.

The art wouldn’t have looked out of place in a mid-century minimalism exhibition; if only its creator hadn’t insisted on attaching so much earthly significance to the pieces.

“Clement Greenberg, asshole that he was, said that art should be made for art’s sake,” the 78-year-old artist told us at the fair's preview on Tuesday. “That’s nice rhetoric, but human beings have been making art since the beginning of time for all sorts of reasons, and they’re all valid.”

Edwards grew up in pre-war Texas, when the state’s black and white populations were still segregated. "When I was twelve my parents explained that there were certain limitations in life," he recalls, "but most of my activities were within our communities, and there were no incidents. People always talk about the Klu Klux Klan, but they were never a threat to us in Houston. I would have loved to have them come into our neighbourhood; that would have been real funny."

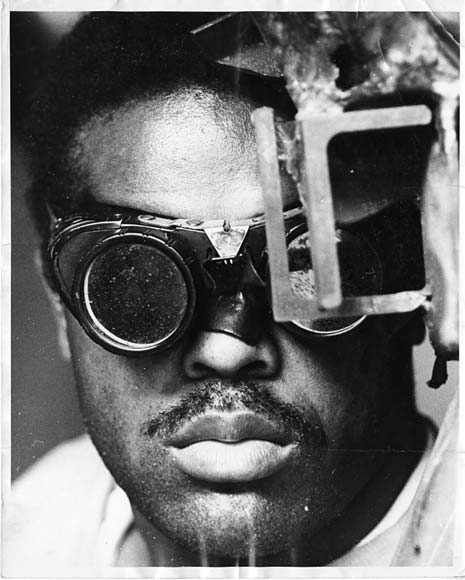

Edwards took an interest in drawing from an early age. He studied in California, received his first solo exhibition for his tightly packed metalwork at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 1965. However, in later life, he struggled to overcome the formalist prescriptions, simplistic historical readings, and yes, the racial prejudices of the age.

“I had my first one-man show in a museum at 26 years old,” he says “I had my first one-man show in a gallery at aged 50. In between, I made hundreds of notes on what to do with barbed wire, and I’ve not created a tenth of what I had in mind. No gallery was interested in me.”

Edwards’ patchy career path wasn’t simply a result of race relations, but also due to prevailing art world notions of influence and value.

“People will say Anthony Caro is an influence, but how can he be?” Edwards explains. “He’s ten years older than me, but started welding one year before me. I couldn’t have been influenced by him, but in the school books, it’s that way around.”

Instead, Edwards prefers to draw other, less obvious comparisons. An early LA commission to fix a series of Jean Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures, led the sculptor to produce his own kinetic, rocking series. Edwards is also an admirer of the American sculptor David Smith; the New York sculptor George Sugarman, known for his colourful works in wood and aluminium; and the Barcelonan metalwork pioneer Julio González.

“You could show González’s [1937 sculpture] La Montserrat, which is his protest against the Spanish Civil; David Smith’s Medals of Dishonor, which is his protest against World War II, and My Lynch Fragments series next to each other,” Edwards says. “There are three generations working in different ways towards similar ideals.”

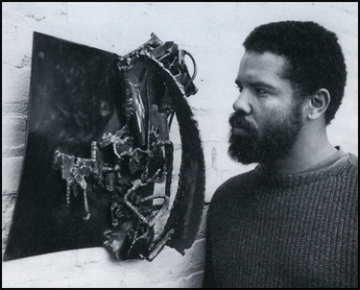

Edwards’ Lynch Fragments are his most famous set of works. The artist has been making these small, abstract metal sculptures, often combining chains, scissors locks and blades, since 1963. The pieces bare similarities to Caro and Smith, though Edwards loaded them with political significance.

“I didn’t want these works to be limited to formalist concerns,” he explains. “I called them Lynch Fragments because you had to consider the subjective potential. Lynching was a specific experience of African-Americans; it was a genocide committed against our people. With that name, you had to accept that the social aspect was a basic part of the art.”

Not every Lynch Fragment is about lynching; nor are they all didactic, protest works. However, the group name enabled Edwards to subvert the prevailing critical prejudices of the time.

“When you look at Michelangelo’s works about the church, you accept the religious aspect, but you don’t ignore the artistic content,” he says. “Back in the sixties and seventies they said ‘no, it doesn’t work like that.’ So, I thought, if I give them the collective, they have to take it seriously.”

Edwards’ uncompromising nature did not endear him to the art world. However, more recently, his chimeric work, which is neither entirely abstract and formal, nor restricted to one simple, political point, has gained favour. Okwui Enwezor included Lynch Fragments in this year’s Venice Biennale International Exhibition, All the World’s Futures; Stephen Friedman staged his first UK solo show twelve months ago, and his full-career retrospective, Melvin Edwards: Five Decades, is currently on show at the Zimmerli Museum within Rutgers University, New Jersey, until 10 January 2016.

Today, Edwards doesn’t think his earlier treatment within the art world was especially egregious or noteworthy, given his background, though he is pleased to have found an appreciative audience later in life.

“Visual art is made to be seen by others. I was never against people wanting to see it,” he says “I just wanted to be who I am in the world.” And perhaps the art world is finally finding a place for that person now.

For more on other 20th century metal sculptors consider our books on David Smith and Anthony Caro; for more on the form generally get a copy of Elements of Sculpture.