Foiling the Forgers with Noah Charney – Vermeer

Our author recalls the time a Dutch forger had to recreate a work sold to the Nazis in order to get off death row

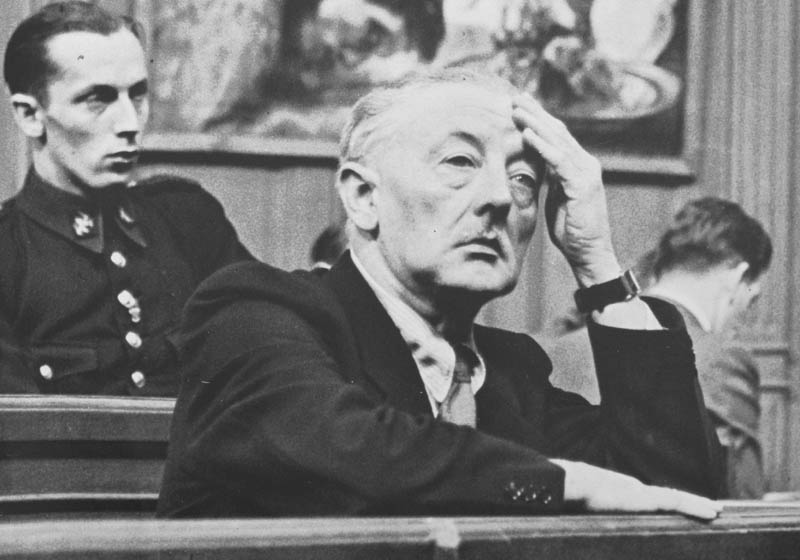

As we all know, to escape punishment, defendants in forgery cases often claim that they thought the artworks they've sold were bona fide masterpieces, and not latter-day copies. However, in 1947 a Dutch painter and art dealer did the exact opposite and only escaped the death penalty after he proved that a canvas passed off as the work of the 17th century Dutch baroque master Johannes Vermeer, was instead a painting of his own creation.

Han van Meegeren had been a moderately successful painter during the early decades of the 20th Century. However, as our author Noah Charney points out in his new book The Art of Forgery “his preferred subject matter, a cross between Surrealism and softcore erotica, was not of the highest levels of taste.”

Unable to find true success with his own works, Van Meegeren turned to forgery in the 1930s, creating and selling on works purporting to be lost paintings by the likes of Vermeer, perhaps as an act of revenge. As Charney sees it, the acceptance of Van Meegeren’s works as genuine would reveal the critics’ ignorance, “while simultaneously demonstrating his prowess.”

Van Meegeren’s scheme was a success; art experts including Abraham Bredius, the leading national authority on Dutch painting, lauded these 'Vermeers' as masterpieces. And it was also profitable; in total his forgeries earned him the equivalent of around $60 million today.

This success is all the most striking given the quality of his craftsmanship. “The first thing that strikes most people who see Van Meegeren’s ‘Vermeers’ is that they look nothing like paintings by Vermeer,” Charney explains, adding that they are much too large and clunky, and feature religious scenes, a subject that Vermeer did not paint.

However, experts including Bredius had long suspected that Vermeer had gone through an early religious stage, and the unveiling of Van Meegeren’s ‘Vermeers’, such as Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery (1942), apparently supported Bredius‘s theories.

Alas, Christ with the Woman Taken in Adultery also led to Van Meegeren’s downfall when, at the end of Workd War II, the work was found in the collection of Hermann Göring, the high-ranking Nazi official. Van Meegeren was accused of selling a piece of Dutch cultural heritage to the enemy, a treasonous charge that was punishable by execution.

After a month on remand Van Meegeren admitted that he had, indeed, painted the work himself. Yet, his methods were so convincing, the court was not immediately won over. For one, Van Meegeren had been very careful to paint with antiquated, natural pigments used by Vermeer. He also guarded against a simple age test, of dripping alcohol onto a painting to dissolve any undried oils, by mixing Bakelite into his paints. What’s more, he achieved a realistic looking array of cracks on his pictures' surfaces by baking his canvases in a large oven.

Despite his protests, experts still believed the Vermeers Van Meegeren had handed were genuine. However, the court did allow him one plausible avenue of defence.

“One of the presiding officers suggested that, if Van Meegeren had painted the Göring Vermeer, he should be able to paint a copy from memory while in custody,” Charney writes.

Van Meegeren seized the opportunity and did indeed create a work that, although not equal to Vermeer’s finest, was certainly a match for the canvas found in Göring’s possession. The Nazi official was even told while awaiting his own execution that the painting in his collection had not been a Vermeer, but a worthless forgery.

Van Meegeren, meanwhile, enjoyed a more welcome reversal of fortune, “from Nazi collaborator, to folk hero,” Charney writes; the wily artist was now “labelled ‘the man who swindled Göring.’” A title at the time that the forger valued far more than a genuine 17th century masterpiece.

For more on the storied history of art intrigue, buy a copy of The Art of Forgery. For more on Vermeer get this great overview. And you can also watch Mr Charney talk through The Art of Forgery in greater depth in this great CBS News interview.