These Brutalist buildings look a bit like Jenga blocks

There are plenty of structures in our new Atlas that look just a little bit like the popular wooden building block game

Both Jenga and Brutalism are almost British inventions. The term ‘Nybrutalism’ – Swedish for ‘New Brutalism’ - had been coined by the Swedish critic Hans Asplund to describe a 1949 building built in Uppsala. A group of young students from the Architectural Association in London are said to have brought the term back to Britain, and, in 1953, the young avant-garde British architects Alison and Peter Smithson took up the term ‘New Brutalism’ for their own work, explains our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture.

Three decades later, the Tanzania-born British national, Leslie Scott, launched Jenga at the 1983 London Toy Fair, presenting a product that she had developed from an old family game Thomas had played while growing up in Ghana in the 1970s.

Whatever the origins, both are now known throughout the world, and it’s fun to look on quite a few Brutalist buildings and mentally retrofit elements of Scott's playful blocks. Here are just a few from Atlas of Brutalist Architecture.

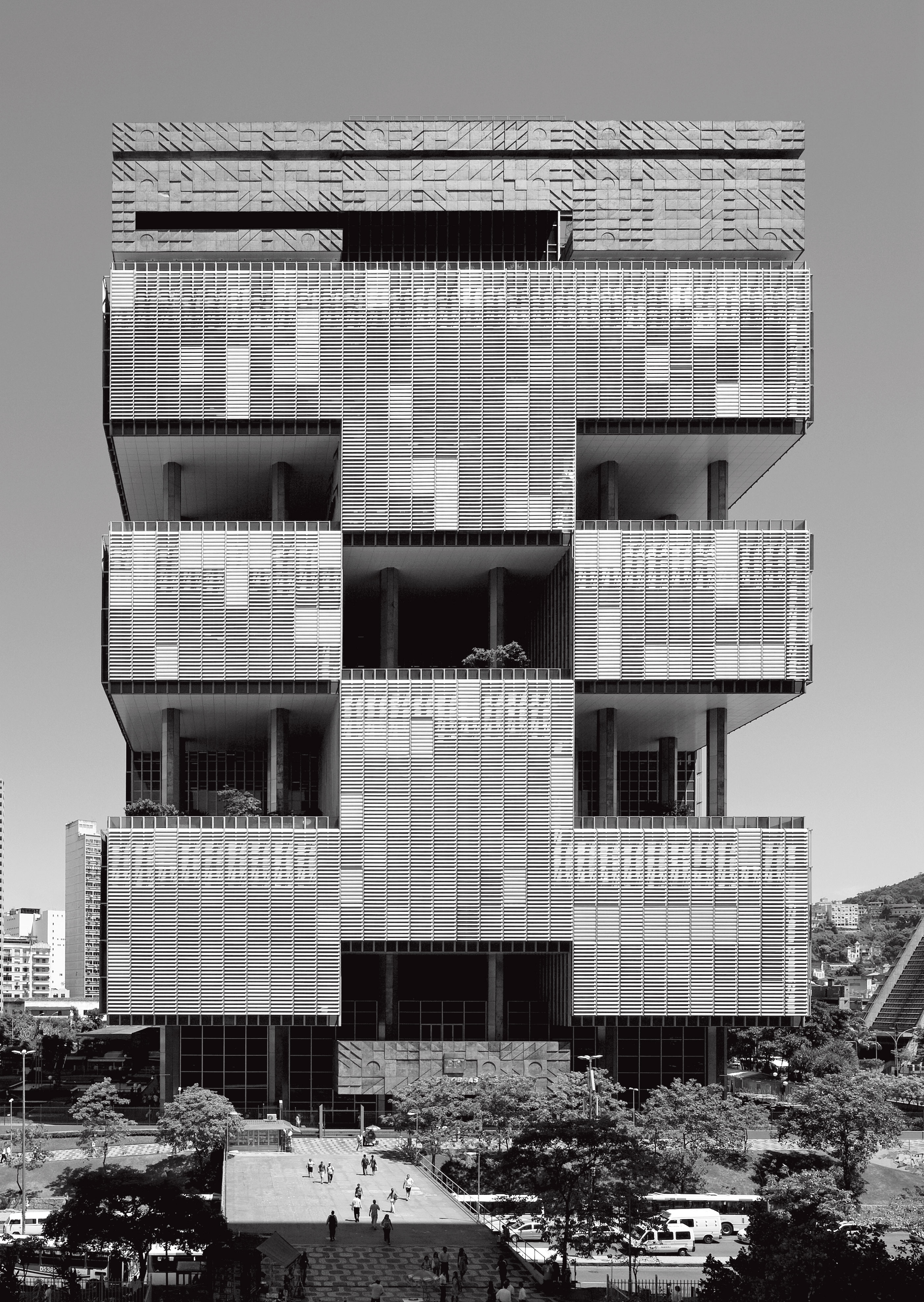

Petrobras Headquarters, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1973, by Roberto Gandolfi and José Sanchotene (top) This 29-storey building is the headquarters of the Brazilian oil company, Petrobras, which struck its first oil field in the Brazilian continental shelf in 1969. The building’s architects Roberto Gandolfi and José Sanchotene broke up this enormous, block-shaped tower with Jenga-style gaps, explains our Atlas, and added plants to “lighten the building’s massing, creating airy spaces for workers.”

Habitat 67, Montreal, Canada, 1967, by Moshe Safdie Though Habitat 67 looks like a playful collection of building blocks, the residential development was in fact a very serious attempt to fix real world problems. “Safdie’s idea started out as an ambitious attempt to explore designs that would simultaneously solve many problems associated with housing provision,” explains our Atlas. “It was to offer the advantages of both apartment living and single-family housing within a high-density environment and avoid the monotony of conventional housing developments

Humanities Building, University of New Mexico, USA, 1974, by Willard C Kruger & Associates There’s a hard logic behind these stacked cubic forms, created by the same firm that oversaw the Los Alamos buildings that housed the Manhattan Project. The building is, explains our Atlas, shaped like military fortresses and bunker, with interconnected hallways, corridors and passage spaces,” enabling the complex to have “a circulation layout that allows people to walk swiftly between the building’s facilities. An elevated walkway surrounds the building to extend the architectural language to the urban landscape.”

Orange County Government Center, Goshen, New York, USA, 1970, by Paul Rudolph This “Cubist honeycomb,” as our book puts it, was created by Paul Rudolph, as bold attempt at spatial complexity. “As Rudolph described it, he wanted ‘the compression and release of space … progression of one space to another’.” HIs designs didn’t prove overly popular with government officials, who moved out in 2011 following a flood. However, public support for the building led to a successful refurbishment, which was completed in 2017.

Ministry of Education, Lima, Peru, 2012, by DLPS Though we might picture this building as a playful pile of blocks, its architects had a more appropriate, pedagogic theme in mind. “Appropriately, the Ministry of Education's headquarters is modelled on a precariously balanced stack of books,” explains our Atlas. “Based on a square floor plate, the project captures attention for its large offset volumes. Although the structure of steel and concrete was detailed with special attention to address seismic threats that are prevalent locally, it looks as if it could topple at any moment.” Just like Jenga, then.

Karaburma Housing Tower, Belgrade, Serbia, 1963, by Rista Sekerinski We see a kids’ game in this block, but locals have named it after another childhood favourite. “This eccentric seventeen-storey high-rise is in the Belgrade district of Karaburma and is a well-known city landmark, known affectionately as ‘the Toblerone Tower’,” says the Atlas. “Built in the form of a hexagon, the pagoda-like tower’s unique feature is its triangular oriel windows. Effectively the building twists around by sixty degrees every three floors.”

Keen to see more? Then get our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture. Presented in oversized format with a specially bound case with three-dimensional finishes, Atlas of Brutalist Architecture conveys the power and strength of over 850 Brutalist buildings - including new, old, demolished and threatened - in over 100 countries featuring the work of nearly 800 architects. the world's finest examples of Brutalist architecture brought to life through 1000 beautiful duotone photographs in one BIG, bold and truly beautiful book. For more beautiful examples of Brutalism of every kind get our new Atlas of Brutalist Architecture here.