Steven Holl on Childhood, China and The High Line

The architect recalls building boyhood tree houses - as well as some more recent and rather trickier commissions

If you happened to be a young kid in the town of Bremerton, Washington State, during the 1950s, and you wanted a cool tree house, there was only one architectural operation to call upon.

“When I was about seven, my brother and I had a two-storey treehouse, an underground clubhouse, and a third building, that was permanently under construction,” the architect Steven Holl, tells us.

Steven and his brother James built their unsanctioned childhood structures from a variety of materials, including wood, corrugated metal and even old carpets, in designs more or less of their own making, as there were few local examples to follow.

“There weren’t any other club houses,” Holl recalls. “I mean, some of the neighbourhood kids helped us, but there was no one else trying to do the same thing. That was one of the great things about it,” he laughs, “no architectural competition!”

Aside from this precocious ability to construct buildings at such an early age, Holl was also good at maths, had a natural flair for creative expression, and came from a family that fostered artistic talent. Not surprisingly then he found his natural vocation very early. “I knew I wanted to be an architect from the age of about five,” he recalls.

Indeed, it was only once he was at architecture school that Holl began to question his ambitions. “The instructors at my undergraduate school at the University of Washington were too pragmatic,” he remembers. “I would have these beautiful ideas, and they wanted me to talk about the rise and run of the stairs. I thought that they were myopic and small minded.”

Holl didn’t find the world of commercial architecture much more welcoming, as a young architect, in New York during the late 1970s. “When I started out, I had no clients,” he says, “so I generated speculative, self-commissioned projects. I think any architect with ambition and ideas does that to get started.”

Among these schemes was the first architectural proposal for the elevated Manhattan railroad that would later become the High Line linear park.

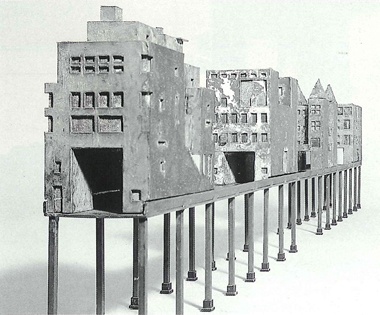

“I started working on the High Line in 1979,” he recalls. “I was there when the last box car went over the highline -- it was a box car of frozen turkeys. I had this idea called The Bridge of Houses,” he goes on. “It involved making the whole of the High Line a public space, and over that pubic space we would construct a series of houses, each of which would be occupied by a different social stratum. There would be single-room occupancy, luxury housing, as well as a hotel. It was meant to represent the richness of the city at that time.”

Holl’s scheme was never built, though he did go on to find great success, at first in the US, then overseas, hitting a particularly hot streak in China around the turn of the millennium. How does Holl account for his success in the world’s most populous nation? He quotes his friend, the late American artist Walter de Maria, who told him, “Steven, you have to be in the right place, at the right time with the right idea.”

“For 10 years in China I had those three things line up,” he says. “I did over 20 projects. I built four really good ones and I didn’t do one bad one.”

Some of Holl’s success rate lay in bureaucratic differences. “In the US, there are all these agencies that have to approve a project,” he says. “In China you don’t have that problem because you don’t have those committees. I’m not sure that’s such a great thing,” he admits, “but when we were building a horizontal skyscraper in Shenzhen, with unprecedented cable-stay technology, we got the building permit in 10 days. If that was in Washington DC they would say “no, change this, and don’t come back until next month.””

Holl says that, today, it takes him around eight years to complete a project; a lifetime for a nascent club-house builder, but a reasonable period for a mature architect who understands that the creation of fine additions to our urban environment cannot be child’s play.

“To realize a good building takes such effort and such a long time,” he says. “If anyone gets a good building up you should just bow down and give them praise!"

For greater insight into Steven Holl’s work both old and new buy a copy of this brilliant new monograph, here. And for more on the High Line, buy our fascinating new book here.